Near the end of 2008, I heard a rumor that someone was painting an extraordinary mural inside the foyer of the Guadalajara Chamber of Commerce. That someone turned out to be artist Jorge Monroy, whose gorgeous watercolors graced the Sunday edition of the newspaper El Informador for some 44 years.

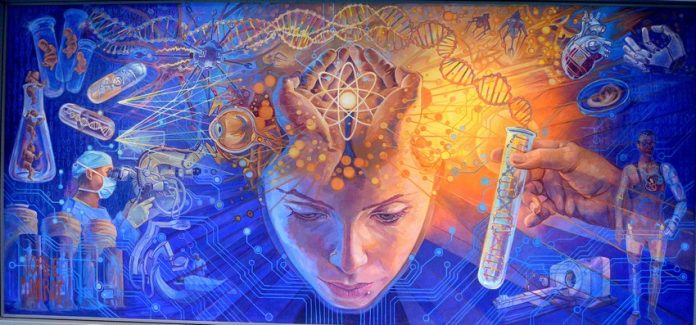

Since then, I have followed Monroy’s career as he created more and more magnificent murals at the Guachimontones Museum, the University of Guadalajara, the Jalisco Water Commission headquarters and the city’s Civil Hospital, just to name a few sites.

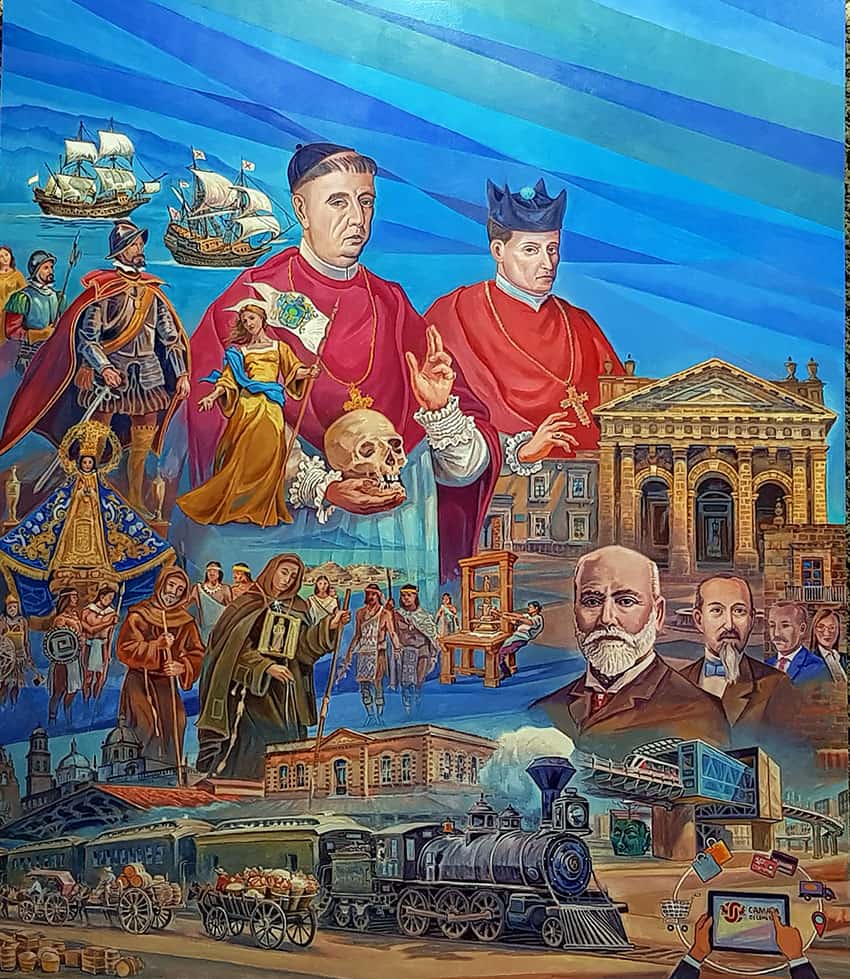

And now here I am in 2021, back in the Cámara de Comercio (Chamber of Commerce) with him, looking at a now-expanded, 68-square-meter mural. Previously called Under the Wings of Mercury, the work is now entitled The Origins of Guadalajara.

“The people in charge here,” the artist told me, “really liked the three-panel mural I did 12 years ago, and since there was a lot of space on both sides of it, they asked me to add a fourth panel, which I painted during the last few months. This bigger mural was dedicated last night, February 11, by the governor of Jalisco and lots of other dignitaries.”

I believe Monroy was asked to add this new panel because of the typical behavior of people who walk into the Chamber of Commerce foyer.

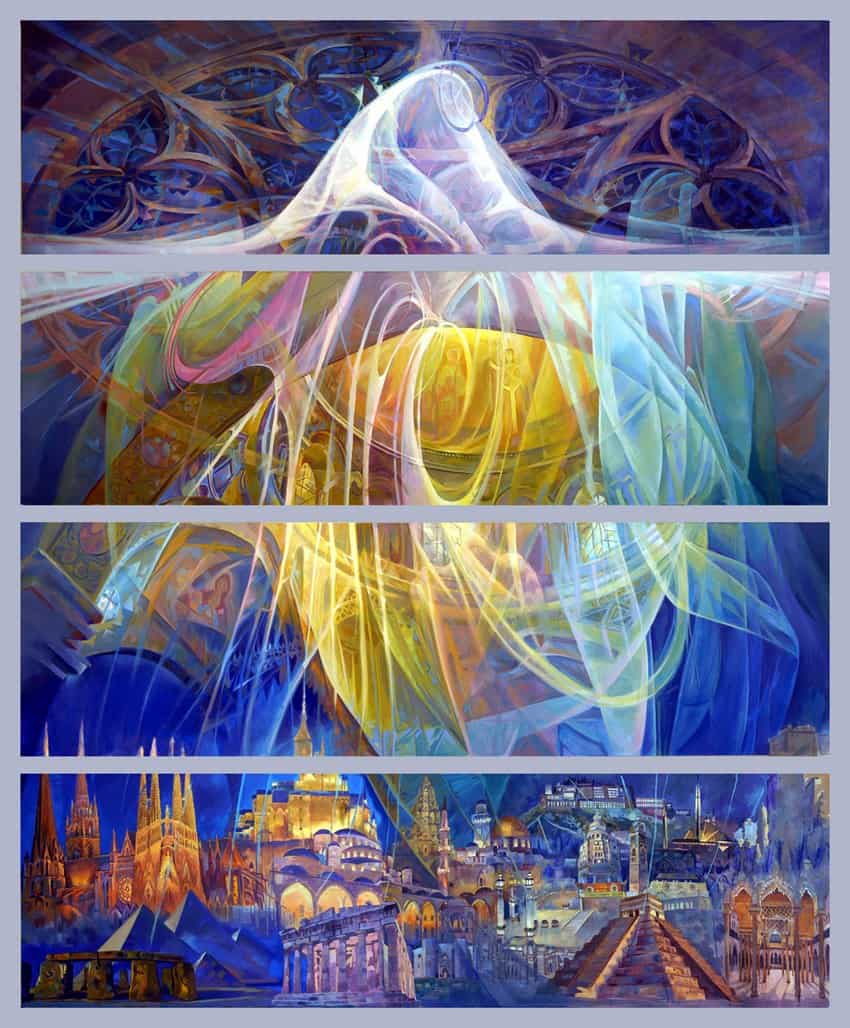

The first thing they do is glance at the mural. Then they stop and take a second look. And once they do that, they’re hooked. Their eye is caught by some iconic building or monument they know very well, and then it gets drawn in by the fascinating little details that the artist has slipped into the painting in a most subversive way, one scene smoothly blending into the next with no jarring change.

“This mural needs no explanation,” Monroy told me. “I’m just inviting people to take a leisurely walk through the streets of Guadalajara.”

Now the expanded mural is even more seductive: the new panel on the left once again presents persons or places we know, interspaced with fascinating images we don’t expect.

In the upper left corner of the new panel, we see some of the Spaniards who tried and tried to found Guadalajara in the 16th century: Cristóbal de Oñate, his brother Juan and the indomitable Beatriz de Hernández. These individuals could generate all sorts of images in a visitor’s mind because there were three earlier attempts to found Guadalajara, each of them fraught with disaster.

But if Mexico’s second city stands where it does today, it is mostly thanks to Hernández, who could not only fight in battle but also knew how to stop a gang of men from squabbling and force them to make a decision.

In the mural, behind Hernández, is Antonio Alcalde, known as “The Friar with a Skull.” It is said that Alcalde got that nickname when he was the abbot of the monastery of Valverde in Spain.

One evening, a group of hunters knocked at the monastery gate, among them the king of Spain.

“We were lost in the woods,” said the king, “and we want to spend the night here.”

Since the king’s visit was unexpected, his majesty ended up sleeping in an austere room adorned by nothing else but a grinning human skull.

“The next morning,” says Monroy, “the king was back in his palace, and the order of the day was to designate a bishop for Mexico. Immediately, the king said, ‘We will send the friar of the skull.’ The king, it seems, had been impressed by the abbot’s wisdom and simplicity. Although he didn’t remember the abbot’s name, he did remember that skull.”

Years later, in Mexico, it was Alcalde who transformed the backwater community of Guadalajara into an important city, founding, for example, its first hospital in 1787 and its first university in 1792. He also brought in the first printing press, which you can see in the mural, just below his upraised hand.

By the way, the features of Alcalde do — for the first time in a mural — actually reflect the true image of the famed friar. We know this based on a recently discovered contemporaneous painting.

To the left of the printing press, Monroy told me, are representatives of the Cascanes, Chichimecas and other indigenous peoples who received the Spaniards with unrelenting all-out war but who were finally pacified by Franciscans like Antonio de Segovia, whom you can see just below Beatriz Hernández.

“He walked about among the most ferocious tribes with a little wooden box hanging from his neck that contained an image of La Virgen de Zapopan, and he somehow got these tribes to lay down their arms, permitting Guadalajara to be founded where it is now in 1542,” he said.

“To the right of the press we see Juan de Somellera, who founded the Chamber of Commerce 135 years ago,” he added. “At the bottom of the panel, there are wagons transporting tequila and handicrafts, while just above them is the train which came to Guadalajara in 1888, allowing its products to be transported throughout Mexico and the U.S.A.

“Finally, at the lower right, we have the recently completed light train that crosses the city — and in the corner, at the request of the Chamber of Commerce, a tribute to online shopping. So as you see, even the internet has found its way into my mural!”

I asked Monroy how he got interested in painting.

“As a child,” he said, “I couldn’t resist drawing everything I could see, from sunflowers to Superman. As a result, I eventually entered the Escuela de Artes Plásticas at the Universidad de Guadalajara. I became a painter … and I knew I would probably die of starvation, so I also became a vegetarian, studied yoga and prepared myself for a life of austerity.”

Instead of expiring in a garret, Monroy managed to keep himself alive by painting watercolors and was even able to marry and raise a family. He has also succeeded in traveling abroad for months on end and always returns to Guadalajara with a portfolio full of acuarelas (watercolors).

“In all these years,” he said, “I’ve never suffered an artistic crisis; my enthusiasm has never diminished. Whatever I see, I want to paint — that’s my problem.”

Jorge Monroy may call it a problem, but to us who savor his exquisite paintings, it is a gift, and truly one of those gifts that never stops giving.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.