Like that of the Mexican War of Independence, the history of the Mexican Revolution can look like a confusing series of armed struggles — few major battles but lots of fighting. However, it is important to understand the basics of what happened in this period of history to understand the Mexico of today.

The Revolution’s official start is marked by an open letter written by Francisco I. Madero urging Mexicans to revolt on November 20, 1910 — hence the upcoming federally-recognized holiday, Revolution Day.

Like all revolutions, this armed conflict was against a political and social system, and the “sins” of that society would shape what would replace it.

That system was the more than 30-year dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, who came to power in 1880 during a century when Mexico’s history was marked by coups, civil wars and foreign invasions.

Díaz’s rule started with a coup, but he managed to stay in power and even bring economic expansion and political stability to the country through foreign investment, political acumen, as well as ruthlessness.

This period of time, called the Porfiriato, was marked by the best and worst of the Industrial Revolution: there were trains, factories and revived mining but also atrocious working conditions, company stores and the dispossession of communal lands into haciendas.

Díaz’s motto was “order and progress,” with the aim of relegating indigenous and agricultural communities to the past and justifying these actions through the academic concept of “scientific politics.”

But the economic progress benefited few and dispossessed many. During the Porfiriato, there were strikes, rebellions and other unrest, but Díaz managed to keep a lid on all that. However, some in the upper classes soured on him as presidential elections under Mexico’s 1857 constitution became a farce, with Díaz “re-elected” again and again.

Then 80 years old, Díaz promised in 1910 not to run again, which set off a flurry of political activity. Díaz reneged on the promise, but not before significant opposition had coalesced around Francisco I. Madero, a businessman and writer with reform in mind.

Shortly before the election, Díaz had Madero arrested and eventually proclaimed himself the winner in a “landslide.”

Madero escaped prison and wrote that open letter calling for armed rebellion against Díaz, later called by others “The Plan of San Luis Potosí.”

This document did not drive Díaz from power, but Madero’s allies — northern strongmen Pascual Orozco and Francisco “Pancho” Villa — mobilized in Chihuahua and began raiding government garrisons. They eventually took Ciudad Juárez, a strategically important city garrisoned by federal troops. This act forced Díaz to resign, and Madero was declared president.

If Madero had been an effective leader, that might have been the end of the story. Unfortunately, he was too idealistic and alienated key allies such as Orozco, as well as Emiliano Zapata, who was angered after Madero became president that he did not make Zapata governor of Morelos and the relationship soured between them.

Counterrevolutionaries pulled off the Ten Tragic Days, a 10-day violent coup in February 1913 that eventually resulted in Victoriano Huerta, the general of the Federal Army, becoming president and Madero being killed.

Villa and Orozco, along with fellow northerners Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón, went back to war, leading a coalition of separate armies that succeeded in ousting Huerta a year later.

But the alliance among the different generals almost immediately faltered. Soon after Huerta’s ouster, the Convention of Aguascalientes was held to try and unify the armies politically, but it resulted in Villa and Zapata forming one faction and Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón forming another. Mexico found itself back in active civil war.

The two sides fought battles until 1915. Villa was defeated at the Battle of Celaya, taking him out of the picture. Zapata’s forces, also defeated, turned to guerrilla tactics.

With the upper hand, but victory not assured, Carranza called for another convention in Querétaro in December 1916. It resulted in the 1917 (and current) constitution adopted in February.

Many of the grievances of the various generals are addressed in this document, having to do with working hours, land redistribution and other economic issues. It also was the beginning of a new identity for Mexico, one that combined the indigenous and the Spanish, supposedly with equal weight.

The ideal of this notion is best seen in the murals of Diego Rivera and other artists who worked in the 1920s and 1930s.

The constitution’s adoption was the beginning of the end, but the Mexican Revolution really petered out rather than conclude with a single battle or treaty. For this reason, there is disagreement as to an ending date.

Many put it at 1920, the year Álvaro Obregón was elected and served his term without getting ousted or killed. But since violence continued sporadically, some put the date as late as Lázaro Cárdenas’s presidency in the 1930s.

Perhaps the biggest change as the 20th century progressed was Mexico’s shift from political power centering on one person to power centering on institutions. The most important of these was the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which would essentially rule Mexico almost unopposed for 80 years.

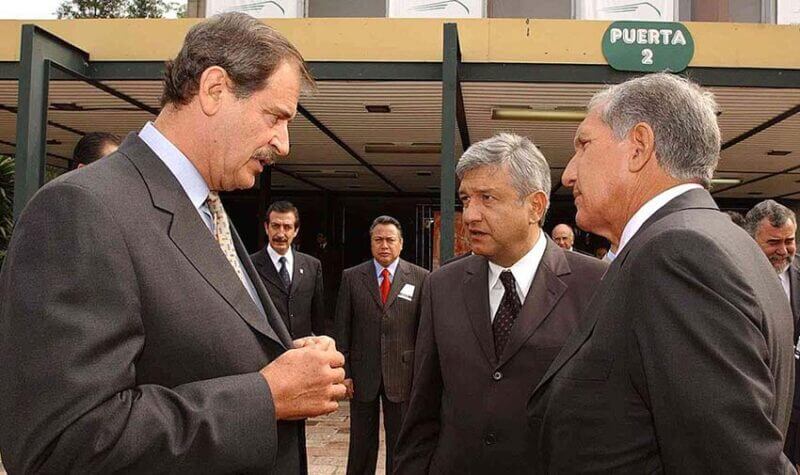

By the time Vicente Fox of the National Action Party was elected president in 2000, the country had soured on the PRI but not the ideals of the Mexican Revolution.

Nowadays, we might be in a transitional post-PRI phase of Mexican politics, but we are definitely not in one where the Revolution ceases to matter.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.