A quintessential example of deep gastronomy throughout Mexico, tamales — those steamed lumps of corn dough wrapped in leaves that can be plain or contain any variety of fillings and sauces — are undoubtedly one of the most traditional dishes in Mexico, if not the most.

If you are not a connoisseur of tamales, you cannot call yourself Mexican. But oh, how to eat them without getting fat.

The tamal is every Mexican’s faithful companion: at six in the morning, sometimes even at dawn, you’ll already find a lady or gentleman selling tamales at a crossroads or on a sidewalk outside one’s local market.

Long before the stores open, the vendors are outside, waiting for the early-morning passersby with a huge pot, from which a cloud of steam is released every time the lid is opened. Inside this pot are several dozen tamales wrapped in corn husks or banana leaves (the latter are Oaxacan-style tamales), looking at us mysteriously from the mist.

In some you can see – sprouting from the center of the leaves – an exuberant filling that’s barely visible: red, green or sometimes yellow or black mole. Each tamal is unique in flavor and can represent a whole cosmogony in itself.

Not even the most adventurous families could possibly know and try all the tamale recipes that are part of Mexico’s vast gastronomic wealth. The National Institute of Anthropology and History has recorded more than 400 recipes; multiply that by nearly 2,000 varieties of tamales influenced by regions and family customs.

Tamales are indispensable at posadas and every important Mexican get-together. They are associated with birthdays, baptisms, weddings and especially the Day of the Dead and funerals. The biggest party associated with tamales, however, is the celebration in honor of Candelaria (Candlemas), which takes place in February.

For me, tamales represent the past. They are the connection with my ancestors — strong women who broke the corn with their arms and lovingly wrapped morsels that can be held in one hand — and can raise the dead.

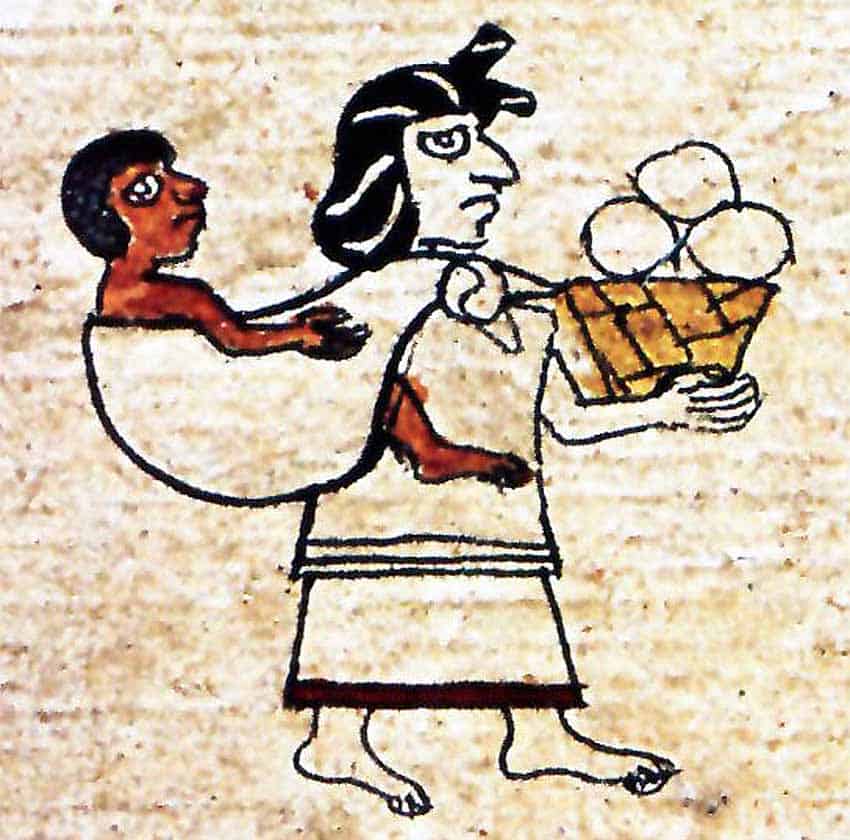

Tamales date back to pre-Hispanic culture. They are sacred food in festivities and offerings to the gods; they appear in the Florentine Codex, a 16th-century ethnographic study of the Mexica people by Spanish friar Bernardino de Sahagún. He described tamales when he wrote that “the Mexica used the meat of turkeys, flamingos, frogs, axolotls, rabbits and fish as stuffing for corn husks.”

One of the famous murals at the Mayan ruins of Calakmul in Campeche that depict life in the ancient city shows a lady offering tamales.

My aunts always made tamales for Christmas, especially pork, mutton, chicken, beans and beef. One Christmas, we even had deer tamales because my uncle had run into one on the road.

I don’t know what I would do without tamales, and that’s why I can’t live outside of Mexico: I would probably become bitter and dysfunctional.

My city, San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato — like many cities and towns in Mexico — has several places to find great tamales: there are ladies selling exquisite ones in front of the local livestock association every morning. But you’d best arrive before 9 a.m. because their two pots of tamales easily run out.

The nuns at the La Purísima Concepción convent will make you tamales in bulk for your event. At a truck stop on the Calzada de La Luz, there are delicious but spicy ones available. Or, if I care to eat sitting down on a Sunday with the family, we can visit the Café de La Parroquia downtown.

We have a saying in Mexico: para todo mal un tamal, para todo bien también. For all the evil, a tamal, and for all the good too.

¡Buen provecho!

Carmen Rioja is the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Atención San Miguel in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato.

- This article originally appeared in Atención San Miguel. It is reprinted with permission and with minor adaptations.