During the conquest of the Mexica Empire, Hernán Cortés faced a challenge from a rival Spanish expedition that aimed to supplant his leadership.

In the end, however, he marshaled enough support to overcome this challenge and later justified his actions through a medieval Castilian legal principle called obedezco pero no cumplo. He noted that he had never received any orders recalling him from his sovereign — Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, the king of Spain — and that had he received any such directive, he would have obeyed it. At the time, however, obeying an order (obedecer) could be understood as listening to it but not necessarily implementing it (cumplir) if the situation on the ground warranted otherwise.

This explanation of Cortés’ use of medieval law to explain his 16th-century conduct is one way in which he and his fellow soldier-adventurers of the Spanish Empire get a more comprehensive treatment in the book Conquistadores: A New History of Spanish Discovery and Conquest by historian Fernando Cervantes.

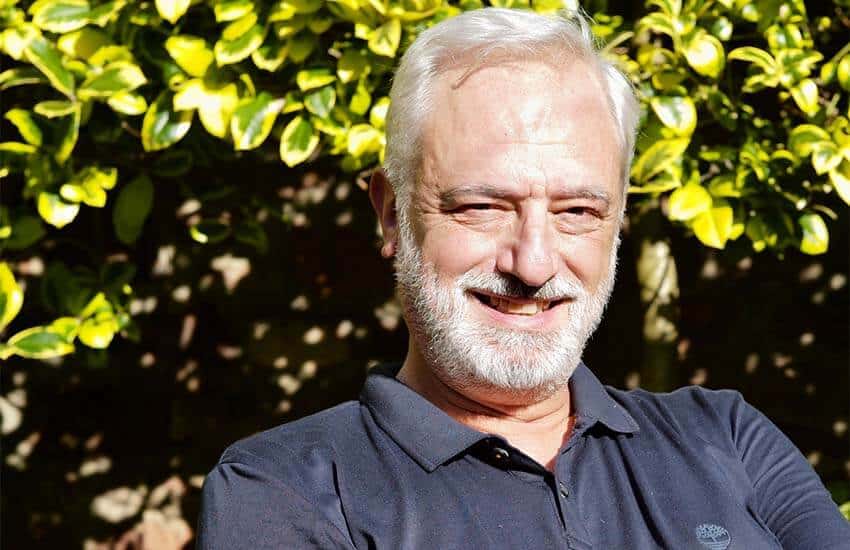

“It had not occurred to me that it was possible to write a history of the conquest that would say something new,” Cervantes said in a Zoom interview. Yet, he added, “every time I sat down to write, at that moment I would see a different angle.”

A professor at the University of Bristol, Cervantes has researched colonial Mexico and early modern Spain for almost 40 years. He has a family connection to several early conquistadors.

One of them, Leonel de Cervantes, was among those who brought the captive indigenous leader Montezuma II to the top of the Palace of Axayacatl in the city of Tenochtitlán in an ill-fated attempt to calm Mexica crowds that had turned against the Spaniards.

“Very soon after, my ancestors began to arrive,” he said. “They were originally from Seville. It was very soon after the conquest.”

Spain’s conquistadors have gotten various reappraisals over the years, with many decrying their collective atrocities against indigenous populations. The book chronicles numerous such atrocities — including a gruesome rampage in Tenochtitlán that led to the Mexica hostility — as well as the deadly infectious diseases the invaders unwittingly brought with them, destroying indigenous populations.

The Spanish-language version of the book has attracted extra interest in the wake of President López Obrador’s call in 2019 for King Felipe VI of Spain and Pope Francis to apologize for the conquest.

“A lot of people contacted [me to ask], do I agree with the president of Mexico? Should Spain and the Vatican apologize?” Cervantes said. “It’s not really the role of the historian. I think it just promotes more polarization to do this kind of thing.”

For Cervantes, the role of a historian is to explain, not pass judgment. “Writing about such a controversial episode [as the conquest] is a good opportunity to exercise that vision of a historian,” he said.

“You have to understand, as far as possible, the context, use primary sources whenever you can,” he added.

That included Spanish and indigenous accounts, ranging from letters to Charles V by Cortés — “the most able of the conquistadors,” Cervantes calls him — to the Nahua Lienzo de Quauhquechollan, a pictorial account of the joint Spanish and indigenous conquest of what is now Guatemala.

A section on mendicant friars addresses their unexpected tolerance of indigenous religious beliefs, although sometimes they were conflicted about this, as was the case with the Virgin of Guadalupe: Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún despaired of indigenous people who saw similarities between their goddess Tonantzin and Our Lady of Guadalupe and preferred to worship the former.

Cervantes also delved into primary sources from Spain before the conquest — including chivalric romances beloved by virtually every conquistador of the era. Romances such as Sergas de Esplandián fed their belief that they were going on crusades against Islam on behalf of Christendom — a belief previously encouraged by millenarian prophecies of the reconquest of Jerusalem and the second coming of Jesus Christ.

Although early conquistadors found connections between these romances and the indigenous people they encountered, Cortés and his men struggled to compare the splendor of Tenochtitlán with anything they had previously seen in Europe.

“All were stunned by the beauty of the place,” Cervantes said. “Cortés was very keen to overstate the beauty of the place [in] writing to Charles V. He wanted to present a majestic jewel. He described to the new [Holy Roman] emperor all sorts of wonderful things.”

Yet, Cervantes said, “At the same time, there was evidence of the ritual sacrifices in the whole of the realm. The structure of Tenochtitlán depended on human sacrifice.”

In command of it all was Montezuma II. Cervantes reassesses the Mexica leader’s role, including his alleged passivity upon the arrival of the Spaniards and their indigenous allies.

“Go back to Montezuma’s ‘state of confusion,’ — allowing the Spaniards to move to Tenochtitlán without any opposition, allowing himself to be imprisoned in the palace of Axayacatl with many of the nobility of Tenochtitlán — in many respects, this account seems a little bit fanciful,” he said. “There must have been some kind of resistance; there must have been a degree of control that the Mexica had. Montezuma knew exactly what he was playing at.”

He notes that the indigenous emperor gained advance knowledge about a rival Spanish expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez and exploited this information, getting Cortés to leave Tenochtitlán to deal with the arrivals. However, subsequent events outpaced Montezuma’s control.

The Spaniards remaining in the capital slaughtered Mexica preparing for the feast of Toxcatl, celebrating the indigenous god Tezcatlipoca. Cortés outmaneuvered Narváez and returned to Tenochtitlán.

Montezuma lost popular support to his brother Cuitláhuac, who was chosen to replace him as leader. He then died after sustaining wounds atop the palace of Axayacatl during a melee.

After Cortes’ return, it became clear that the tide was turning against the Spanish, and the conquistadors prepared to escape Tenochtitlán by night, part of an event known as La Noche Triste (the Night of Sorrows), in which the Spanish and their indigenous allies were attacked as they tried to flee and sustained heavy casualties.

The Mexica still had a chance to end the invasion at La Noche Triste, Cervantes believes.

“They could have finished off [the Spaniards] then and there,” he said. “Most Spaniards would have just gone back [home] after that.”

However, Cervantes said, that’s where the “character of Cortés” comes in.

“He left Tenochtitlán with knowledge of the basic weaknesses of the city. It depended on imported supplies. Stop the supplies, and it starves to death. It’s exactly what he decided to do.”

Cortés got invaluable help from indigenous communities such as the Tlaxcalans — a common story in the history of the conquistadors.

“We would not be able to expect the conquest of Mexico or Peru with the resources the Europeans had at their disposal,” Cervantes reflected. “It would have been impossible to achieve feats like these on their own.”

The indigenous communities that sided with the Spaniards often found common cause with them, Cervantes said, citing evidence in the Lienzo de Quauhquechollan, in which the Nahua are portrayed with white skin like the Spaniards.

“Many, many indigenous societies were very keen to form alliances with the Spaniards in order to fight their enemies,” Cervantes said. “They very often identified with the Spaniards much more willingly than [with] indigenous enemies.”

As for how the conquistadors saw themselves, Cervantes said they had a very different way of looking at the world.

“We need to constantly remind ourselves they were not any less intelligent or any less ignorant than you and me,” he said. “We have to enter a conversation in their context.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.