When Ilan Stavans first learned about the Popol Vuh as a teenager growing up in Mexico City, he was fascinated by the millennia-old Mayan tale. Decades later, Stavans reconnected with the text and saw it as comparable to other foundational narratives from world civilizations, such as the Bible. Yet he noted a key difference: unlike these classics, the Popol Vuh had remained obscure.

Now Stavans — an acclaimed scholar of the humanities, Latin America and Latino culture at Amherst College — is helping modern readers connect to the ancient story that began as an oral tradition among the K’iche people, who are part of the Maya.

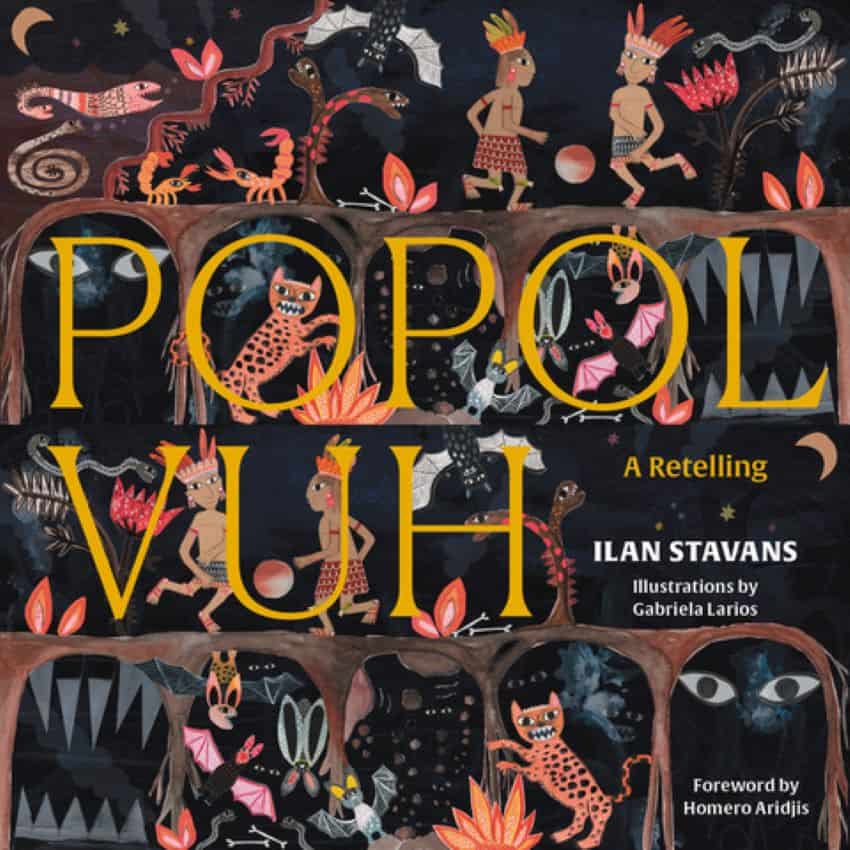

Stavans has released Popol Vuh: A Retelling, a book-length version of the narrative that he hopes will interest a mainstream audience. The book features illustrations from Salvadoran artist Gabriela Larios, whose artwork provides a crucial dimension, Stavans said, as does the foreword by Homero Aridjis, Mexico’s former ambassador to UNESCO.

“My intent in this retelling was to insert the Popol Vuh into the canon of world classics, sagas that represent the birth and development of a nation,” Stavans said. “I have always been puzzled by the total absence of pre-Columbian indigenous aboriginal narratives that tell the story of the various peoples of the Americas prior to the arrival in 1492 of the Europeans in a way that is comparable to The Iliad and the Odyssey, to the Nordic sagas of Beowulf and other similar stories, and even to religious texts like the Bible, the Ramayana, and the Quran.”

Stavans drew multiple comparisons between the Popol Vuh and these texts.

“If you see the Ramayana, if you see the Bible, you see literary texts that tell us stories about the gods and humans interacting,” he said. “Stories like the Ramayana are about genealogy, explaining how a people acquired its identity, what its mission is in life.”

That’s what he sees in the Popol Vuh, which he describes as “a beautiful story” about “how the world was created. At the center of it are fallible humans. Within the humans, there’s a kind of selection of one people that is going to honor the deities. That people are the K’iche.”

Stavans lamented that when he was younger, the Popol Vuh and another foundational Mayan text, the Chilam Balam, were treated as anthropological or archaeological items, not as books. He said that he was “angry at the way [that] throughout Mexican history, indigenous cultures had been, like many people in time, fossilized, turned into fossils, seen as historical artifacts, historical entities, not incorporated in any meaningful way into the lens of daily life in Mexico, and even less so in Mexican culture.”

He said that today, translations of the Popol Vuh exist primarily in scholarly or poetic editions. He decries what he describes as a shortage of translations for popular audiences, which he said is not the case with classics such as Beowulf. He notes that on rare occasions, translations of the Popol Vuh have been released by mainstream houses or by independent nonprofit publishers like that of his version, released by Restless Books, of which he is the head. He notes that his version is a retelling, not an exact translation. He describes it as an attempt to reach readers with modern sensibilities.

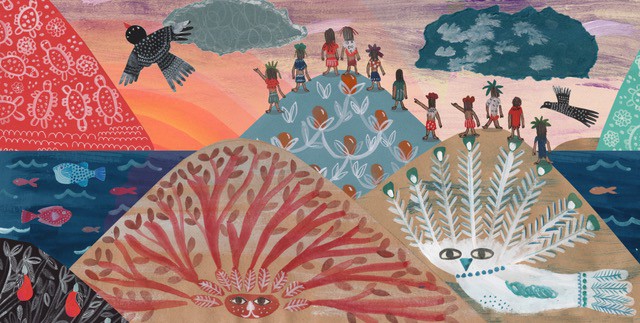

In this regard, he sees Larios’ illustrations as vital. Her artwork depicts the gods, demigods, animals and humans of the narrative — including the demigod twin brothers Junajpu and Ixb’alanke, who undergo a difficult journey into the underworld of Xibalba.

“I thought Gabriela would be wonderful for this retelling,” Stavans said. “We would work back and forth,” until the text and artwork were “kind of woven together.”

He also praises the foreword from his friend Aridjis, whom he describes as an activist for ecology and indigenous cultures.

Some of the animals in the Popol Vuh appear in another book by Stavans published this year, illustrated by the Mexican artist Eko — A Pre-Columbian Bestiary: Fantastic Creatures of Indigenous Latin America.

According to Stavans, the Popol Vuh began as an oral tradition among the K’iche, who have roots in Chichicastenango, Guatemala, as well as in Chiapas, the Yucatán and El Salvador. With each retelling, the story was modified, although certain characters, metaphors and themes remain, he said.

One theme is duality: God has two K’iche poetic names, Heart of Heaven and Heart of Earth. The world is divided into an upper realm and an underworld, or Xibalba, which Stavans likens to the Christian hell or purgatory.

Many characters in the narrative are siblings — or even twins, including Stavans’ favorite characters, Junajpu and Ixb’alanke.

Junajpu and Ixb’alanke seek to avenge the deaths of a previous set of twins — their fathers — at the hands of the Lords of Xibalba. In the underworld, they survive a roomful of jaguars and a chamber of fire, but a vampire bat decapitates Junajpu. However, his brother creates a fake head out of a chilacayote squash to fool the Lords of Xibalba. Although both brothers ultimately die, they return to life and conquer Xibalba.

Stavans said that one thing he loves about the Popol Vuh is that he sees “a lot of magical realism here even before it became a fixture in Latin American literature” such as in the works of Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortazar.

In the Popol Vuh, “objects can do supernatural things, animals can speak … all some of the elements that make this, I would say, an animistic book. It’s very endearing, almost to the point where you can say it could be children’s literature, except it’s very violent.”

The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors interrupted the oral tradition, and the Popol Vuh risked becoming “on its way to oblivion,” Stavans said. However, in the late colonial period, a Dominican friar named Father Francisco Ximénez preserved the narrative in written form through indigenous scribes, the first in a series of transcriptions.

“Father Ximénez had the idea to put pen to paper,” Stavans said. “It’s a critical moment in any people’s history.”

Yet, he is unsure of Ximénez’s motives, wondering whether “the colonizers also had some hand in shaping the narrative.”

Several elements in the text “are very close to how the Bible describes the beginning of the world,” Stavans noted, adding that Ximénez and other missionaries may have been trying to “infiltrate the minds of the storytellers. It’s hard to know.”

“It feels to me almost a usurpation, to be honest, to refer to Father Ximénez as kind of an author,” Stavans reflected. “He’s the medium, the bridge.”

Portions of the Popol Vuh continue to be told among the K’iche, who have suffered since the Conquest, according to Stavans.

“The plight of this indigenous people is a very challenging one,” he said. “Poverty, illiteracy, illness, alcoholism … These are the echoes of what happened during the colonial period; they’re still experiencing them, day in, day out. In many ways, the Conquest has not finished.”

Yet, he said, there is also a heroic story of survival.

“We have this book, we have this people that link us to the past.”

And, perhaps, to the future.

“[The retelling] came out around a very specific moment, when we’re all looking for different kinds of roots,” Stavans said, “with Black Lives Matter, with the search for more multidiverse backgrounds, with Latinos looking to understand their past in more native ways, connected with indigenous culture. It has touched a chord.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.