Having explored caves in such far-flung places as Jamaica, France and Saudi Arabia, I naturally wanted to keep the tradition when I moved to Mexico in 1985. The first thing I tried to do upon settling in the hills outside Guadalajara was to find a caving club in Jalisco.

However, when a letter to the editor of México Desconocido magazine produced no results, my wife and I founded our own club, named Zotz, which is Mayan for “bat.”

In every pueblo we visited, we asked whether there were any caves nearby. If we got a sí, it would inevitably be accompanied by one of the following remarks: a) the cave is full of treasure or b) The cave is full of mal aire (bad air). If this article were about the treasure, I wouldn’t have much more to say, but mal aire turned out to be very real indeed and impacted our lives again and again.

“Cuidado,” they would tell us. “More than 30 people in our town have died over the years from breathing the air in that cave.”

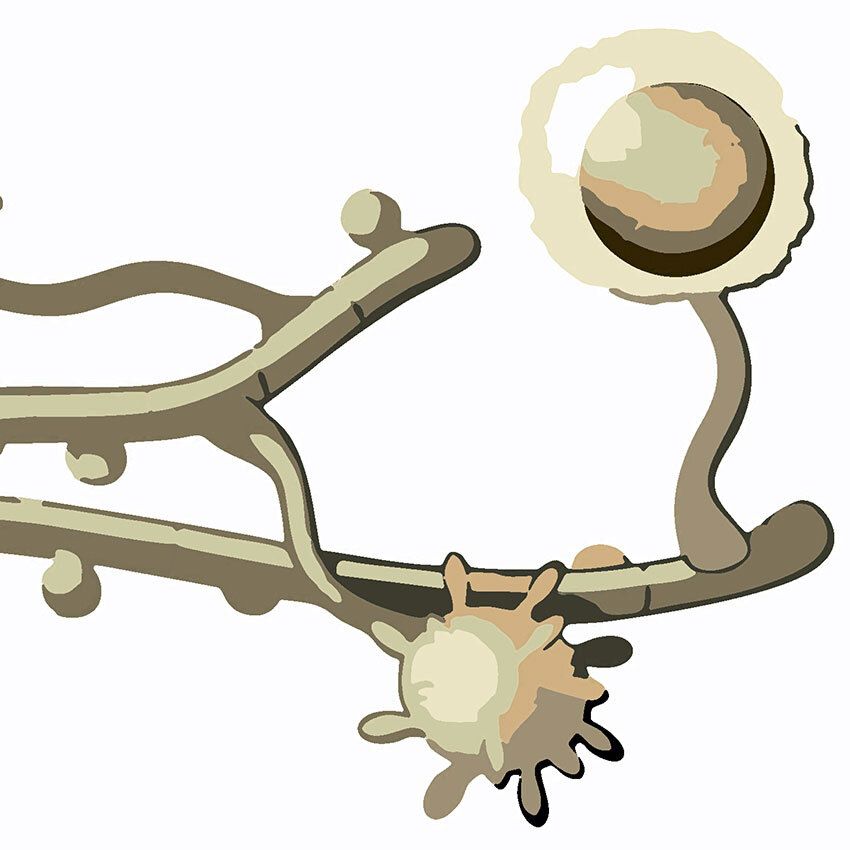

It didn’t take long for us to find out that it wasn’t the air that was bad but something floating in it: the tiny spores of the fungus histoplasma capsulatum, which loves to grow on guano, the droppings of bats or birds. The spores are invisible to the eye, and you won’t know they’ve found their way to your lungs until 11 days after you’ve visited the cave — the typical incubation period in western Mexico.

Once your immune system discovers the invader in your lungs, it tries to encapsulate it. You experience a cough, perhaps accompanied by chest pains and a fever; the symptoms vary tremendously. One person may experience what seems like a passing cold while another may be hospitalized for a year. Yet another may die from histo while still others may notice nothing and then come down with a persistent cough years later.

Naturally, it occurred to us that people entering a cave should wear masks to prevent breathing in the spores. So we tried that … and the following case indicates our results: in 1988, a group of 17 people, both adults and children, many of them with no previous experience in cave exploration, visited a cave with a small vertical entrance.

Most of these erstwhile explorers were from Mexico, but two were from the United States. Many of them wore a simple cloth face mask that they removed for photos while in the cave.

Eleven days later, the leader of the group, Mario Guerrero, started receiving phone calls.

“How do you feel? Do you have something like the flu?”

Mario soon discovered that everyone, including himself, had similar symptoms: headache, a fever up to 40 C, exhaustion, respiratory congestion and, for most, a hacking cough. He contacted a Social Security (IMSS) clinic, which asked all 17 of the explorers to come in for X-rays.

“You all have histoplasmosis,” said the doctor. “Please go tomorrow to IMSS headquarters for more tests.”

The next day, in Mario’s words, “they examined our blood, our stools, our urine and our spit … and then they again told us to come back tomorrow.”

“What about the medicine?” Mario asked. “What should we take?”

“There is no medicine,” the doctor said. “You should rest, eat well and wait. It will probably go away in two weeks.”

“What?” members of the group exclaimed. “So why should we come back tomorrow?”

“Oh, we’ve never seen a case like this before,” the doctor answered. “Seventeen people with histo … It might be a record! What a great opportunity for a study!”

Later, Mario told me, “Sixty days after entering that cave, everybody in the group felt normal … and ready to go off and explore another one.”

Questions about masks and histo later provoked lively debate among members of the U.S. National Speleological Society. Tests were carried out, with the conclusion that masks can indeed protect a caver from histo spores but only if that mask is sealed around the edges to the wearer’s face; that’s bad news for bearded spelunkers.

A few years later, IMSS Guadalajara had a second case of numerous individuals infected with histo, only this time they had not been in a cave. Instead, they all worked for the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). They were put into the hands of the late Dr. Amado González Mendoza, who learned that all of them had been digging ditches in a certain place.

Dr. González discovered that dirt taken from one meter below the surface in that area contained numerous histoplasma capsulatum spores which, it was surmised, had been present in guano dropped by bats flying over the place long, long ago. Nevertheless, the spores were still alive and able to grow.

Dr. González then had a study done of the subsurface around Jalisco. He discovered histo spores in many places. When he showed me a map of the worst areas, I told him, “Doctor, your map looks like a guide to the caves of Jalisco. These are exactly the places with large outcrops of limestone.”

While doctors typically prescribed no medicine to the victims of histoplasmosis 30 years ago, today the situation is much improved. Says a doctor at Guadalajara’s Hospital Civil:

“My husband is a speleologist, and after years of caving in Mexico he ended up with a persistent cough that hounded him day and night for months. They x-rayed his lungs and found nothing, but when they gave him an MRI, they found a nodule, which was calcified, in one lung.

“A biopsy revealed a great deal of inflammation in this nodule, as well as the presence of other smaller nodules. So he was put on itraconazole, which is effective against fungi not only in the lungs but in the throat, nails or skin. The treatment is oral but slow. After several months, the cough disappeared.”

At first, we thought only caves filled with tons of guano presented a serious risk to visitors. As time passed, however, we realized that any dry, dusty cave or mine probably hosts the fungus.

Then, unfortunately, a group of visitors to a very wet river cave came down with histo, every one of them triathlon athletes.

We could only surmise that currents of air from the lower part of the cave 100 meters downstream, where bats roost, had carried spores all the way to the nostrils of those unfortunate young visitors.

Our final conclusion: you can’t be sure that any cave is completely safe — and Jalisco might just be the histo capital of the world.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years, and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.