Foreigners who come here to live and end up staying for decades provide a unique perspective on life in Mexico.

In 2019, I had the fortune of interviewing Guatemalan-born artist Rina Lazo. Although a major muralist in her own right, she was best known as the last surviving assistant to Diego Rivera. She embraced this legacy, in no small part because the Mexico she discovered in the 1940s was “her Mexico.”

Mexico has received immigrants for a long time, including us English speakers. Like other immigrants, we have “push” and “pull” factors. Dire poverty generally is not one of them, but economics plays a role, as it does for retirees looking to stretch pensions.

But those of us who come at younger ages are a different breed, often dissatisfied with life in our home countries. We don’t quite fit in, and we’re looking for something different.

Bob Cox literally joined up with the circus as a young man in the 1960s, making his way to Tlaxcala, where he has lived since the 1970s. Dr. Stan De Loach ran away from home at age 14 to find a family in San Miguel de Allende. Teacher and artist Helen Bickham came to Mexico on vacation in 1963 with her husband and two small children. She then told her husband that he could return without them.

A distant second reason is politics. San Miguel and Ajijic started as havens for bohemians over 80 years ago. In the 1970s, some from antiwar and student protest movements found their way to Mexico despite the fact that the country had its own problems with the 1968 Tlatelolco student massacre and its aftermath.

Richard Clement and Bruce Roy Dudley came in part to avoid the draft. John Falduto’s mother came in 1980 in part because she did not like the political direction of the country, with him following her lead in 1992.

Mexico’s “pull” is the promise of an alternative.

The decision to come to Mexico and the decision to stay are often two different things. Most came here on vacation, for something job-related or to just pass through. Australian Jenny Cooper had to sail through Panama to Europe because the Suez Canal was closed by war, Patsy Du Bois came to study Spanish and Karen Windsor came to study Mayan archaeology.

If I had a peso for every time I heard something like “I was only going to be here for X amount of time, but then I met Y.”

Some are whirlwind romances. German-born Kiki Suarez was on her way around the world in the 1970s, stopped in Chiapas, met her husband and then looked for a way to make life work in San Cristóbal long before its current fame. Bonnie Sims came to Acapulco on vacation at age 19 and got involved with a local fellow. After returning to Canada, she wondered why she left and found her way back to Mexico.

Most met their future spouses in a much less-rushed manner, but that relationship was still central to the decision to stay. Peace Kat in Oaxaca flatly states that her spouse is why she remained, as she had a promising art career in Miami.

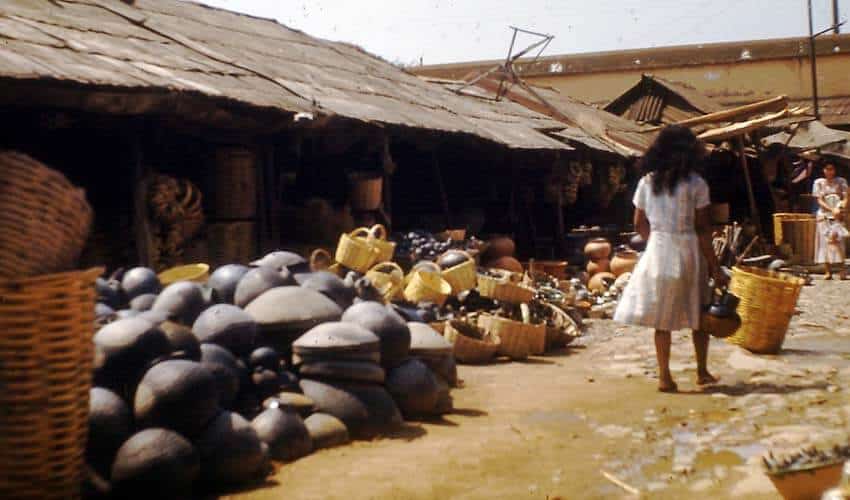

But generally, staying is due to a mix of love for their spouses and for life in Mexico. They describe Mexican culture as “less hectic,” “less materialistic” and more “person-” and/or “family-oriented” than in the United States and Canada and Europe. People cite everything from family interactions to just being able to chat with vendors at local markets.

Mexico experienced a devastating earthquake in 1985 and the long-awaited fall of the Institutional Revolutionary Party’s 71-year dynasty in 2000, but interviewees’ comments on changes in Mexico since the late 1970s relate to improvements in infrastructure and the opening of Mexico’s economy, starting with NAFTA.

Some have stories of losing significant money during Mexico’s peso devaluations in the 1980s and 1990s, and especially 1994, but others, because they had foreign income, were not so affected.

Many, including the most bohemian, appreciate the improved access to products from the rest of the world these days, even if they feel somewhat embarrassed by it. Canadian Karen Windsor admits, “It might be a sin, but I enjoy it.” But she also notes that economic decentralization allows cities like her Guadalajara to develop.

Negative comments about globalization’s effect on the country are more related to how local communities have changed rather than how it’s affected Mexico as a whole. Everyone in San Miguel de Allende complains about waves of newcomers, for example, even if they like that the municipality has changed from a “dusty town” to a cosmopolitan center.

Peace Kat and Eric Eberman both bemoan the loss of local dress, traditions and foods in Oaxaca and Chiapas respectively.

Long-termers tend to have reservations about commenting on more recent political and social issues. Hardly anyone has citizenship, even after decades of living here, and so they are not permitted by law to participate in Mexican politics, including taking part in political action, like civil protests.

One exception is Eberman, who has been an activist for environmental issues in Chiapas, a dangerous occupation for Mexicans and foreigners.

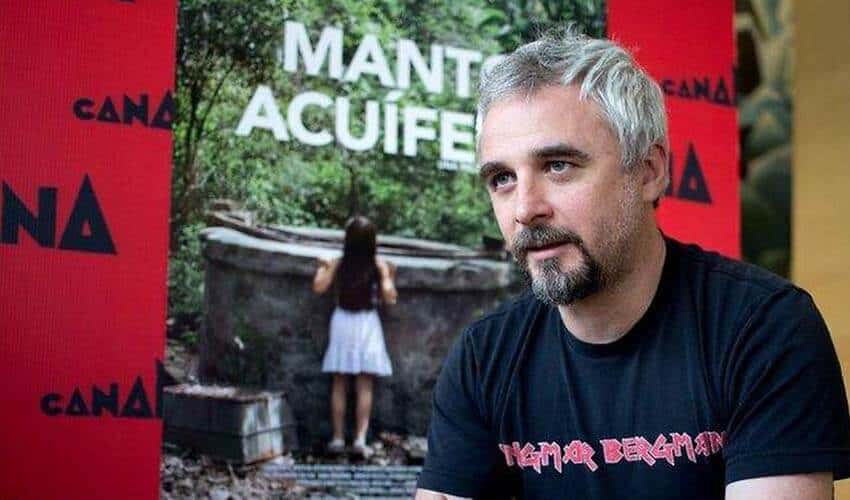

One thing that maybe should not have surprised me was how many of my interviewees had formed connections with Mexican families of prominence at the local or national level. For example, Australia-born director Michael Rowe is married to the current minister of culture, Alejandra Frausto.

Another surprise was that my interviewees were not quite as nostalgic for “their Mexico” as Lazo was. The consensus seems to be not only that “things change,” but the essential for them — Mexico’s people — are who they have always been.

- Special thanks to Patricia Grace Perrin Marion, Joanna Van der Gracht, Richard Carr and Alan Mould for their insights.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.