A Spanish Jew practicing his faith secretly in 16th-century colonial Mexico is jailed by the Inquisition for heresy and for leading Mexico’s underground Jewish community. His prison diaries and other texts on Judaism he writes there are discovered and used to sentence him to death. The texts are the earliest example of Jewish writing in the Americas, held in the National Archives until they’re stolen in 1932. A researcher accuses a rival academic of the theft, but the manuscripts remain missing until 2016, when a U.S. collector spots them for sale in New York City.

The intrigue-filled odyssey of the diaries of Luis de Carvajal el Mozo (the Younger) — from their creation to their disappearance to their return to Mexico City in 2017 — reads like a plot for a Dan Brown novel, but it really happened.

When Baltzar Brito, director of Mexico’s National Library of Anthropology and History, first laid eyes on the manuscripts in New York City in 2016, he says he “knew in his heart they were the originals.”

Brito was on a team of experts from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History and its Culture Ministry sent to authenticate the diaries after collector Leonard L. Milberg alerted Mexico that he had bought them and wanted to return them to Mexico.

Experts on Judaica in Mexico City and around the world were atwitter at the news that a holy grail of early Jewish writings had finally been found — the first known Judaic writings in the Americas.

Luis de Carvajal, el Mozo, a Portuguese poet, calligrapher, merchant and devout Jew was part of a well-to-do and powerful New Spain family. His uncle, Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva, was a conquistador who was made governor of Leon for his victories in the New World but made an enemy of the viceroy of New Spain, Lorenzo Suárez, who was determined to destroy the entire family and take their lands.

Suárez denounced the family to the Holy Inquisition for secretly practicing Judaism, punishable by death. Luis de Carvajal el Mozo was arrested by the Inquisition but released and told to convert to Catholicism. De Carvajal instead became a leader in Mexico’s underground Jewish community. Arrested a second time, he would not survive his second round of imprisonment. But during his second incarceration, de Carvajal continued writing his diaries and other musings on his faith.

Before he was eventually executed, says Dr. Alicia Gojman de Backal, a history professor at the National University of Mexico in Mexico City, de Carvajal was tortured so badly, including being pulled on the torture rack, that he revealed the name of 120 fellow Jews, including his mother, sisters and best friend Miguel de Lucena. De Carvajal’s captors forced him to listen as these “heretics” he had named, including his mother, were tortured in the cell next to his, Gojman de Backal says.

Unable to cope with having turned in his family and friends, he tried to commit suicide in jail but failed. His diary details how he fell to his knees in anguish at one point listening to his mother’s screams as she was pulled on the rack.

“His spelling is a bit difficult [to read] because it has two types [of script], one more careful and another [not] because, apparently, he didn’t have proper conditions in which to write,” says Brito.

The diaries were discovered and used against de Carvajal when he testified before the Holy Inquisition. Condemned to death, he was burned at the stake on December 8, 1596, in Mexico City’s public plaza along with his mother, sisters and de Lucena.

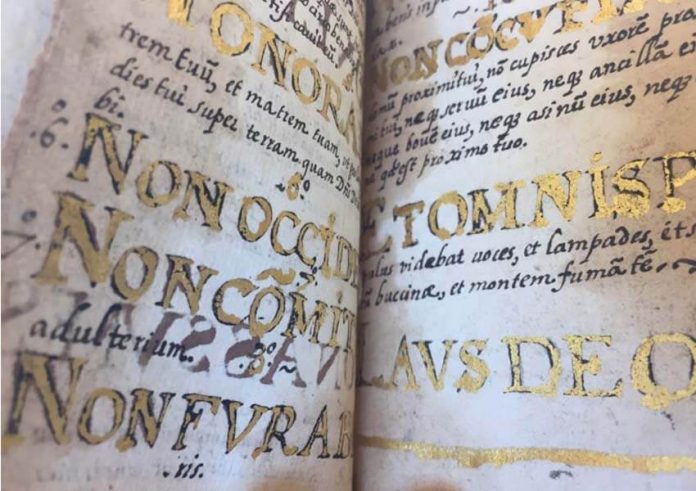

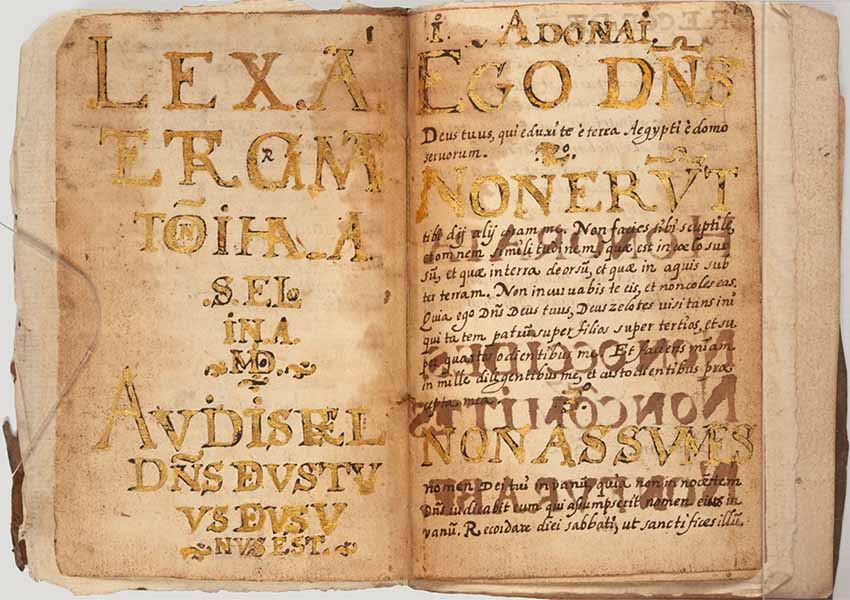

De Carvajal’s writings consist of three manuscripts — The Memories of Luis de Carvajal, The Law of God, and The Way of Worshiping God and Devout Exercise of Prayer, which addressed how to pray during Yom Kippur. The diaries are adorned with calligraphy and gold leaf scraped from a Bible. More than 400 years old, they’re in perfect condition. Although they were signed with the pseudonym of “Joseph Lumbroso,” they were verified by handwriting comparison to have been authored by de Carvajal.

All three became part of the Inquisition’s records and eventually part of the Inquisition Collection at Mexico’s National Archives. For centuries, the diaries were studied by researchers from around the world.

Then, in 1932 the diaries — which consisted of three separate manuscripts — disappeared without a trace. A historian on the National Archives staff who was writing a book on de Carvajal accused a rival, Jacob Nachlin, a visiting Yiddish-speaking professor of Jewish and Polish History, of the theft.

Nachlin spent three months in jail, but since the diaries were not found, he was eventually released for insufficient evidence. Some scholars believe his accuser may actually have been the guilty party. The mystery of how they disappeared and how they ended up in London has never been solved.

In 2015, the manuscripts first appeared in the catalog of Bloomsbury Auctions in London, which listed them as 17th- or 18th-century works by an unknown author. When asked, Bloomsbury said the diaries came from the library of a family in Michigan who had them in their possession for decades. The three manuscripts were being sold as a set for US $1,500.

Purchased by a rare book dealer, they turned up again in New York City in 2016 at an auction house, which listed them as “replicas.” Renowned collector Leonard L. Milberg became suspicious. He felt it would have been nearly impossible for someone to replicate the calligraphy and microscopic text written in Latin and Spanish.

Milberg contacted some scholar acquaintances, and they agreed that the replicas could be the originals stolen from the National Archives in Mexico. He contacted the Mexican consulate in New York City and in his Manhattan office, Milberg made a 40-minute presentation to Consul-General Diego Gómez Pickering and convinced him of the manuscripts’ authenticity and historical significance.

The fact that they were being auctioned gave them both a sense of urgency. Pickering set the diplomatic machinery in motion and had Brito fly to New York to authenticate the diaries.

Brito analyzed the handwriting and the paper, written on beaten cloth with a type of ink used in the 16th century, and confirmed that the diaries were indeed the originals. After their authentication, Milberg agreed to donate the manuscripts to the Mexican government after they were first displayed in a New York Historical Society exhibit entitled The First Jewish Americans.

On March 21, 2017, the 450-year journey of the diaries came to an end. They were returned to Mexico City where, after being digitized in Spanish and English, they were safely stored in a climate-controlled vault.

BNAH Assistant Director José Guadalupe Martínez said that the manuscripts represent “the seed of Jewish literature in America, which makes it a brave document.”

“Luis de Carvajal is not a man of letters as such,” he said, “but he has an impressive memory and he cites Old Testament prayers without error; he was a very erudite man.”

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán last year and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.