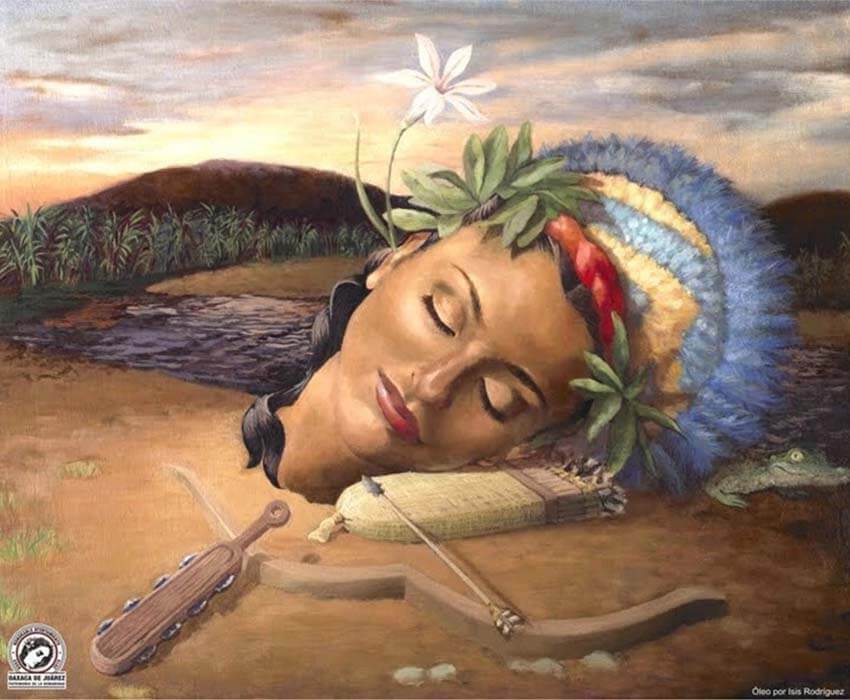

Long ago, legend says, a shepherd found a wild lily growing in what today is San Agustín de las Juntas, a settlement near Oaxaca city’s airport. When digging to collect the flower by its root, he discovered the head of Donají, a Zapotec princess. This beautiful, decapitated, royal head is today the city’s official emblem.

This foundational story is exemplary of Oaxaca, a magical land inhabited by magical people, where the geographies of language and biodiversity intertwine, enveloping and nourishing one other over millennia.

These all evolve together while sharing the same spaces and the same challenges — animate and inanimate — that humanity faces today in its efforts to save our blue planet. It’s a human-nature communion so profound that the Zapotecs here — the Cloud People, as they call themselves — believed that they descended from rocks, trees and jaguars.

I have no doubt that was the case.

Oaxaca’s land is the cosmic daughter of a complex geological history. That history has sculpted archetypal symbols on its topography and on the minds of its people, shaping a limitless range of landscapes — from the Pacific coast and through dry tropical forest; through scrublands, temperate pine and oak forests; and into the triumphant ascent into the cloud forests of the Cerro Nube (Cloud Hill) at 3,720 meters above sea level.

It is the land of the Mixtec princes Tres Pedernal, the incarnation of the values of Mexico’s indigenous women. It is the land in which Los Chimalapas lies — that breathtaking half a million hectare home of Mexico’s last remaining intact tropical forest, which unfurls across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Oaxaca is the exquisite outcome of an assortment of natural blessings that have encouraged adaptive radiation (i.e., rapid evolutionary species diversification), speciation (when nature creates a new offshoot species) and an extraordinary mix of flora and fauna that has blended elegantly with indigenous peoples and languages.

The state’s name comes from huaxyácac (“in the nose of the guaje plants” in the Náhuatl language), a native tree with white flowers and red and green pods (the three colors of the Mexican flag, before that flag even existed) that conceal tasty seeds.

Centuries ago, when the Spaniards arrived, they called this land Guajaca, Segura de la Frontera, Tepeaca and Antequera; but the Náhuatl won over the Spanish, and today it continues to be proudly called Oaxaca.

For over 10,000 years, a wide variety of indigenous peoples have spread and flourished in these diverse environments: the Zapotec, Mixtec, Mazatec, Mixe, Zoque, and many more, as well as Afro-Mexicans, mestizos and Spanish thriving together on this tricolor nose of guajes.

Today, more than 4,000 indigenous communities in Oaxaca speak 157 languages, making up 43% of Mexico’s languages. More than 8,400 species of plants (40% of all the plants in Mexico) and 4,500 species of animals (half of the country’s vertebrates and 19% of its invertebrates), make Oaxaca Mexico’s most bioculturally diverse (meaning both highly biologically and culturally diverse) state.

This is why Oaxaca is a biocultural planetary treasure.

It’s also why there exists no gastronomy like Oaxaca’s: seven multicolored moles, rock broth, Ixtaltepec wedding stew, large and crunchy tlayudas, tamales, the hearty beef and bean soup caldo de gato, chapulines (grasshopers), escamoles (ant larvae), maguey worms, chicatanas (ants), chiles stuffed with sardines, the sweet treat nenguanitos, the ancestral drink pozonque and Oaxaca’s version of the tostada known as memelas.

And, to appease everyone’s alcoholic and nonalcoholic thirst, Oaxaca offers 77 traditional elixirs, including mezcal (such as Amores, my favorite), tepache, aguardiente, popo, pulque, champurrado, bu’pu, and pinole.

Oaxaca is divided into 570 municipalities, of which 418 are ruled by the “uses and customs,” an autochthone form of self-governance. Towns such as Espinal, Santo Domingo Tehuantepec, Juchitán, Puerto Escondido, Huatulco, Mitla, San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, San Pedro Pochutla, San Bartolo Coyotepec, Miahuatlán de Porfirio Díaz and Teotitlán (meaning among the houses of God in Náhuatl) de Flores Magón blow the minds of all travelers.

Oaxaca is so desirable that even the souls of those who die, longing for their homeland, choose to hang around after their bodies have long gone. Each November 2, on the Day of the Dead, the souls of all those who were born in Oaxaca and passed away — including its most famous artists, presidents, dictators and anarchist journalists — wander the graveyards and streets and may reveal themselves to the living, but only the living who believe.

If you find yourself in Oaxaca city on that day and you walk the streets at night, you may encounter the souls of Oaxaca’s two most celebrated and loved Zapotec painters: Francisco Toledo (and his magical erotic animals), who succeeded in preventing a McDonald’s from opening on the capital’s zócalo; and Rufino Tamayo, whom you will see carrying his mural Day and Night, which symbolizes the struggle between daytime (the feathered serpent) and nighttime (the tiger).

Or you may find the souls of the writers, José Vasconcelos and Andrés Henestrosa; but they will reveal themselves only if you have read at least one of their books.

Whether you like their music and voices or not, you will certainly encounter the souls of violinist-pianist Macedonio Alcalá performing his waltz and Oaxaca’s de facto anthem, “Dios Nunca Muere” (God never dies), and Álvaro Carrillo, Chuy Rasgado and José López Alavés singing “Sabor a Mí,” “Naela” or “Canción Mixteca,” an ode to all Mexico’s migrants.

And if you care about the rights of indigenous peoples, you may meet the soul of Benito Juárez, Benemérito de las Americas. Born in San Pablo Guelatao, Oaxaca, to Zapotec parents, as president of Mexico he fought for the best causes, including separation between church and state, freedom of the press and the subordination of the army to civil authority — causes for which we Mexicans continue to fight hard even today.

And if you are one of those willing to take risks, you might also wander, preferably at midnight, by Cerro del Fortín. There you may have the opportunity to confront, face to face, the soul of Porfirio Díaz — the politician, soldier and president-turned-dictator. For 30 years and 105 days, he ruled Mexico.

No doubt, however, General Díaz will be in a rush, being chased by his fierce opponents, the souls of the three Flores Magón brothers — fomenters of the Mexican Revolution who would be loudly heralding their anarchist newspaper Regeneration.

But if you chose to only walk near Santo Domingo — that matchless baroque temple built by persevering Dominican priests in the mid-16th century — try hard to listen to the song La Llorona that tells the sad story of the young Zapotec man in love, saying farewell to his wife, who cried despairingly when her beloved husband was swept away to his death by the winds of the Mexican Revolution.

But if you are really lucky, you might also have the chance to listen to Oaxaca’s five living hummingbirds — Lila Downs, Natalia Cruz, Martha Toledo, Alejandra Robles and Susana Harp.

All this is true, although you may choose not to believe it.

And, if you wish to see the universe in motion, come to Oaxaca on July 16 and stay the two Mondays after. Those are Los Lunes del Cerro (Mondays on the Hill) — pre-Hispanic rituals worshiping the goddess and protector of maize.

Centuries ago, these rituals culminated with the sacrifice of a damsel representing the goddess, rituals that many years later turned into the Guelaguetza, a Zapotec festival thanking the agriculture gods for the harvest, and in which all people, rich and poor, participate without any class distinctions.

The Guelaguetza ends with the Dance of the Feather, in which the principal dancer (the sun) moves in circles to talk to other dancers (the celestial bodies) with diagonal movements representing the winter solstice and parallel movements representing the spring equinox. As I have told you, the cosmos is moving.

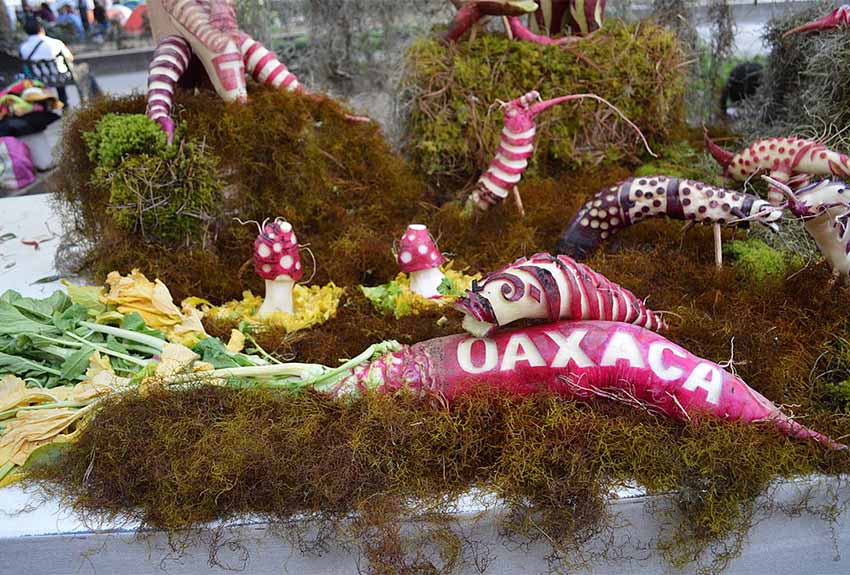

Thirty-three years ago, on December 23, 1988, I visited Oaxaca for the first time. That night was the Noche de Rábanos (Night of the Radishes), when local artists display figures that they have lovingly carved from leviathan radishes.

It seems like yesterday that I wandered through the streets of Oaxaca de Juárez, young and alone while devouring with heart and soul a myriad of colorful animals, humans, houses and countless other exquisite forms carved out of beautiful specimens of Raphanus sativus, offered to me as gifts by artists I did not know.

It seems like yesterday that I found refuge in a cold and somber church, comfortably sitting near a bowl filled with holy water and realizing that I had just arrived in the most magical place on Earth.

• Respectfully dedicated to Josefina and other Zapotec women of white heads and rebellious hearts who initiated me into the magic of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and whose distant relatives lived there 10,000 years ago.

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and the former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.