After several musicians in the Jalisco Philharmonic Orchestra — all of them expats — had told me that they had had very rewarding experiences at a temazcal near the ruins of the Guachimontones circular pyramids, 50 kilometers west of Guadalajara, I decided to investigate.

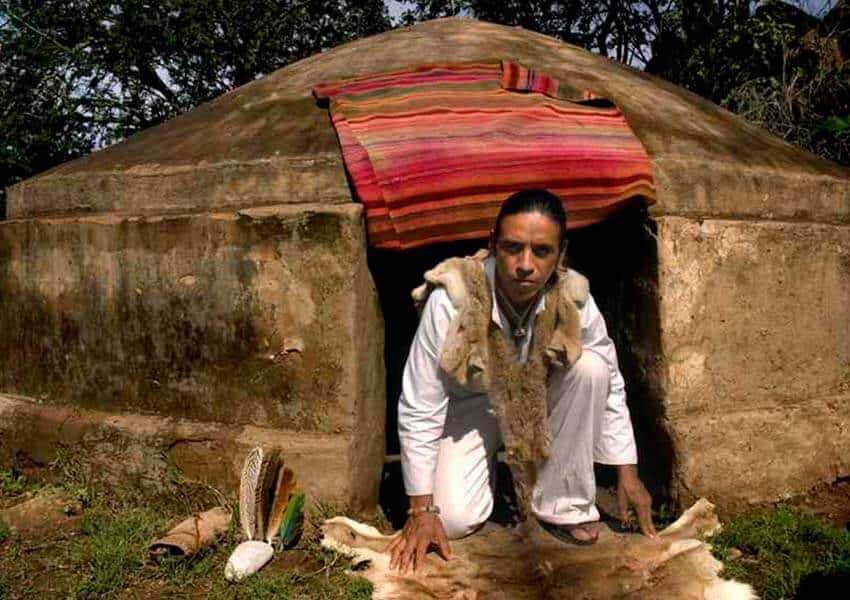

The temazcal is the Mexican version of the traditional sweat lodge that has been in continuous use by native peoples of North America for as long as civilization has existed. In this part of Mexico, the sweat lodge takes the form of a round, one-room construction made of adobe that can hold about a dozen people. It has one very low door and no windows except for a small hole in the roof.

The word temazcal is said to come from the Náhuatl word temazcalli. The verb tema means “to bathe” and calli means “house.”

This temazcal was built by Godofredo Oseguera, founder of Proyecto Mixcouatl, which is dedicated to the preservation of pre-Hispanic traditions.

Oseguera says that the temazcal has always been used for a variety of purposes, including physical and mental health, communication with immaterial beings and far more mundane ends such as the processing of grana cochineal (insects used to produce crimson dye) and the smoking of corn seeds to protect them from insects.

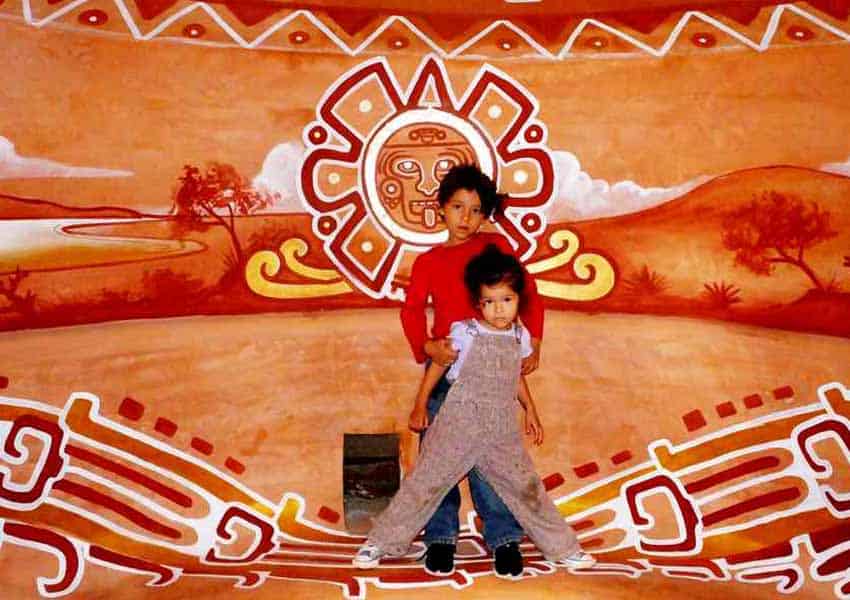

Symbolically, the temazcal ritual represents a return to the womb, a renovation in which participants hope to find the inner child they may have lost contact with.

As far as health goes, the most important benefit of the temazcal is said to be cellular regeneration. The steam supposedly produces negative ions that are breathed in and directly affect the body’s cells, regenerating them. Positive changes in one’s health due to frequenting a temazcal are said to eventually translate into psychological benefits such as anger control, balance and self-confidence.

I received permission to attend Oseguera’s temazcal session and arrived on a Sunday morning.

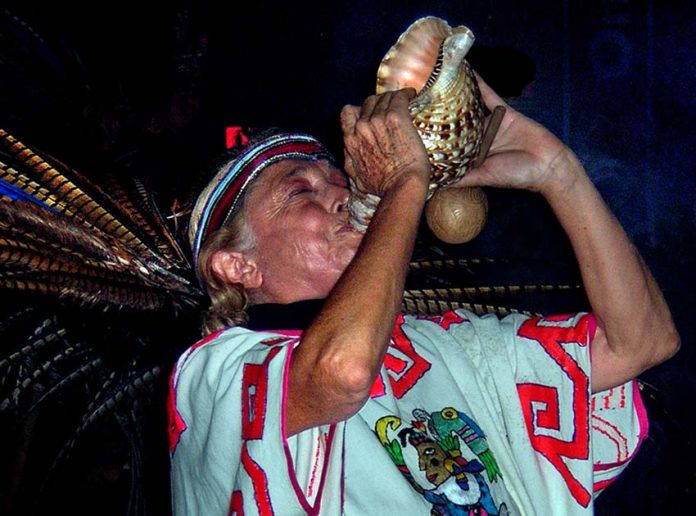

The ritual, as Oseguera practices it, begins with a ceremony on a flat spot inside a circle of rocks under the open sky. Participants place offerings of flowers, fruit or seeds inside the circle and, as a conch shell is blown, face the four cardinal directions one by one, giving thanks for the benefits that have come to them from the north, south, east and west.

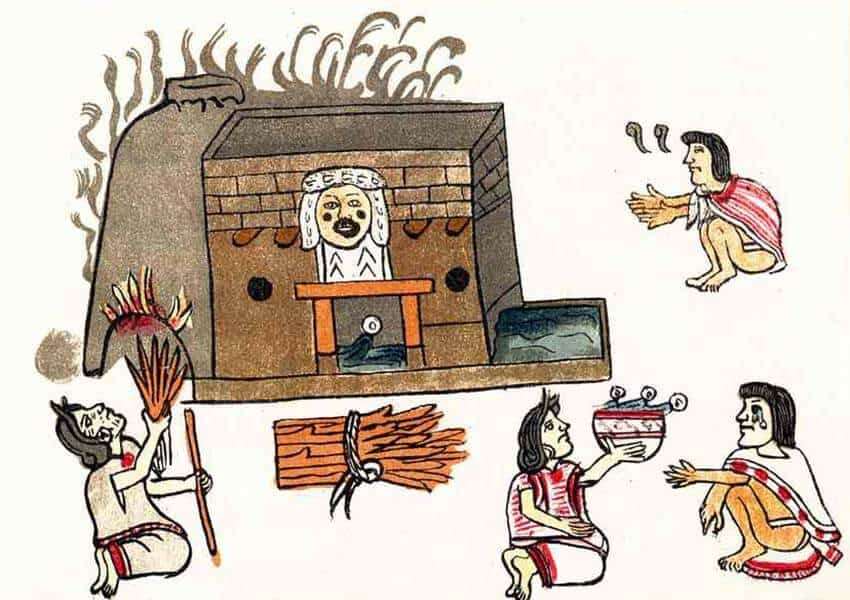

Participants enter the temazcal in a predetermined order. Red-hot volcanic rocks are then brought to the door. Each rock is greeted with the words, “Bienvenida, abuelita” (Welcome, grandma) and rubbed with copal incense.

The rock itself is considered our ancestor and wise beyond measure because it has been around for eons and knows Earth’s entire history. A pair of deer antlers were originally used to receive and place the rock — which is about 20 centimeters in diameter — into a flat depression in the center of the floor. When a sufficient number of abuelitas have been “seated,” the heavy cloth door is closed.

The participants are now invited to say a few words about what they are asking for or hope to gain from their experience. Next, the person in charge picks up a thick bundle of aromatic herbs (sage, eucalyptus, marigold, rosemary, thyme, lemongrass, etc.); dips this large “brush” into water; and then thoroughly wets both the abuelitas and the people sitting around them. Huge white clouds of water vapor now fill the small room, reducing visibility to almost zero. Even the narrow ray of light from the ceiling hole can barely be seen.

After several such ablutions, the participants are sweating profusely. Through the swirling white clouds comes Oseguera’s voice: “If anyone would like more heat,” he says, “you can move closer to the center of the room.”

Several people actually do this. They are in training to endure “the warrior’s temazcal,” which features much higher temperatures than the normal one.

Time passes. More rocks are brought into the room. More water is thrown on them and onto the participants until the air seems thick enough to cut with a knife. Now a strange whistling sound can be heard, coming from the well-saturated rocks.

“The ancients called this ‘el canto de las abuelitas’ [the song of the grandmas],” comments Oseguera.

By this time, a psychological change has taken place inside the temazcal. The participants have shifted around, some sprawled out on the floor. They talk freely to the entire group. It’s a bit like a therapy session. There is talk of dreams, absent spouses, learning Spanish, living with cancer. Most speakers cannot be seen through the haze, but everyone participates. A woman experiences a new awareness. “Bienvenida a la niña interna,” (Welcome to your inner child) says Oseguera.

Twenty years ago, Oseguera was learning ceramics from indigenous people in the coastal town of El Tuito, Jalisco. At a certain point, they invited him to their local temazcal. For five years, he attended on a regular basis. One day, his friends announced they were giving him a gift.

“The gift they gave me was the honor of managing the temazcal,” said Oseguera with a smile. Later, he expressed the desire to have his own sweat lodge. “You must only build [it] on your own property,” he was told, “and you should only buy land after that land has first invited you to do so.”

Several years later, the right conditions for constructing a temazcal presented themselves to Oseguera. “There was a zapote tree near Teuchitlán under which I loved to sit and read,” he recounts. “Some strange things happened to me under that tree, and then one day a man came up to me and asked if I would be interested in buying the property on which I was sitting — for a very low price. I felt that this piece of land had indeed called to me and that the time had come for me to build my own temazcalli.”

In some places, the temazcal ritual has been “watered down,” so to speak, or blatantly turned into just another tourist attraction, but Oseguera continues to offer traditional temazcal sessions. Beginning in September of 2022, he will welcome visitors to his new Crow Rock Center, in Jalisco’s Sierra del Águila, a 90-minute drive from Guadalajara, two hours from Lake Chapala.

If you’d like to have a real temazcalli experience, send him a message on WhatsApp at 384-101-5379, and an English-speaking friend of his will contact you.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.