In a previous story, Bats Up Close and Personal, I made the case that most bats are every bit as clever, loving and loyal as dogs but that we humans don’t give them credit for these characteristics because most of us know them only as fleeting silhouettes in the night sky. But in Mexico, this is especially a problem.

Here, this prejudice against bats is far stronger because among the more than 1,400 species of bats in the world — which eat everything from insects to fruits and lizards to fish — there are three species that feed off the blood of other animals. One of them, Desmodus rotundus, or the vampire bat, has developed into a serious issue among cattle ranchers in Mexico, one that can be traced back to practices initiated by the Spaniards in the colonial era.

Before the conquest, vampiros were few and far between, typically nipping Mexican wild turkeys in the foot and lapping up (not sucking) some of their blood. Then the Spaniards introduced corrales, which resulted in great numbers of cows and horses being practically immobilized outdoors.

For Desmodus rotundus, every corral was a free restaurant, and the number of vampire bats in Mexico has been growing steadily for centuries, creating a kind of Koyaanisqatsi, or Life-Out-of-Balance, situation in rural Mexico.

Besides leaving unsuspecting cows and horses with open wounds, vampire bats often leave them with paralytic rabies. When a rancher sees one of his animals after another die a slow, horrible death like this, he can’t be blamed for wanting to seek out the culprit’s home and blow it to bits.

If a rancher or farmer has never had a close-up look at those mysterious flyers of the night, he may easily assume that all bats are vampiros. And that’s a problem.

This was precisely the situation we found in the hills above El Ojo de Agua (the spring), a Jalisco town we were visiting because we had heard rumors that there was a cave in the area.

The first person we met was a one-armed man named Paulo. Though he didn’t know us from Adán and Eva, Paulo gave us a warm welcome, invited us to a tatemada (barbeque) and a dip in a spring-fed pool. He even offered to put us up in the guest house of the local hacienda.

Paulo was delighted to discover that we were cave explorers as he was one of those many country people who are thoroughly convinced that every cueva contains a hidden treasure, which you will surely find if you dig long and hard enough.

The following day, we followed Paulo up a steep mountain trail for about four hours, heading for a cave he knew about. This is easier said than done when the temperature is in the neighborhood of 30 C and the humidity is 100%.

However, Paulo’s frequent reminders that “this cave goes all the way through the mountain” kept us moving, even though we had heard such claims before (only the caves usually ended a mere five meters beyond their entrances).

Finally, we came to the cave entrance at the bottom of a bushy fold in the hills. To our surprise, the opening was completely covered by a patchwork of chicken wire mesh held tightly in place by barbed wire and a framework of stout branches. “What’s this all about?” we asked.

Paulo explained that the cave had been filled with dreaded vampiros, but luckily, the local ranchers had “taken care of the problem.”

With Paulo’s permission, and with the help of pliers, we undid one end of the formidable barricade and climbed inside.

We found ourselves in a passage about two meters high and strewn with large chunks of fallen rocks from the ceiling. Following this slowly for about half an hour, we checked for side passages and photographed several large stalactites. Then we saw a light.

“Maybe we’ve finally found a cave that does go straight through the mountain,” we quipped. To our surprise, it turned out to be true.

Then, as we entered a wide room with a high ceiling, we saw that this second entrance was sealed with another bat barricade.

We backtracked, and as we approached our starting point, my wife Susy spotted a very low crawlway on the side. She disappeared into it and a few minutes later we heard a tiny voice shouting: “It goes! I’m in a huge room!”

A few minutes later, we were in a spacious new section of the cave. The floor was covered with a thick, spongy layer of guano. Examining it closely, we could see the wings and legs of countless digested insects.

The farther we walked, the more we were convinced that many thousands of insect-eating bats had once lived here. Now there was not one to be seen.

The texture and the reddish color of the walls brought a special beauty to this passage. Soon we were threading our way among giant boulders.

We did plenty of climbing both up and down but never needed a rope. This challenging and enjoyable passage finally came to an end … and, yes, there in front of us was light — and once again the ominous silhouette of chicken wire and branches.

At this moment, we could almost feel the panic that all those bats must have experienced. Had they been caught on the inside like us — trapped, flying desperately from one entrance to another in a futile attempt to find a way out?

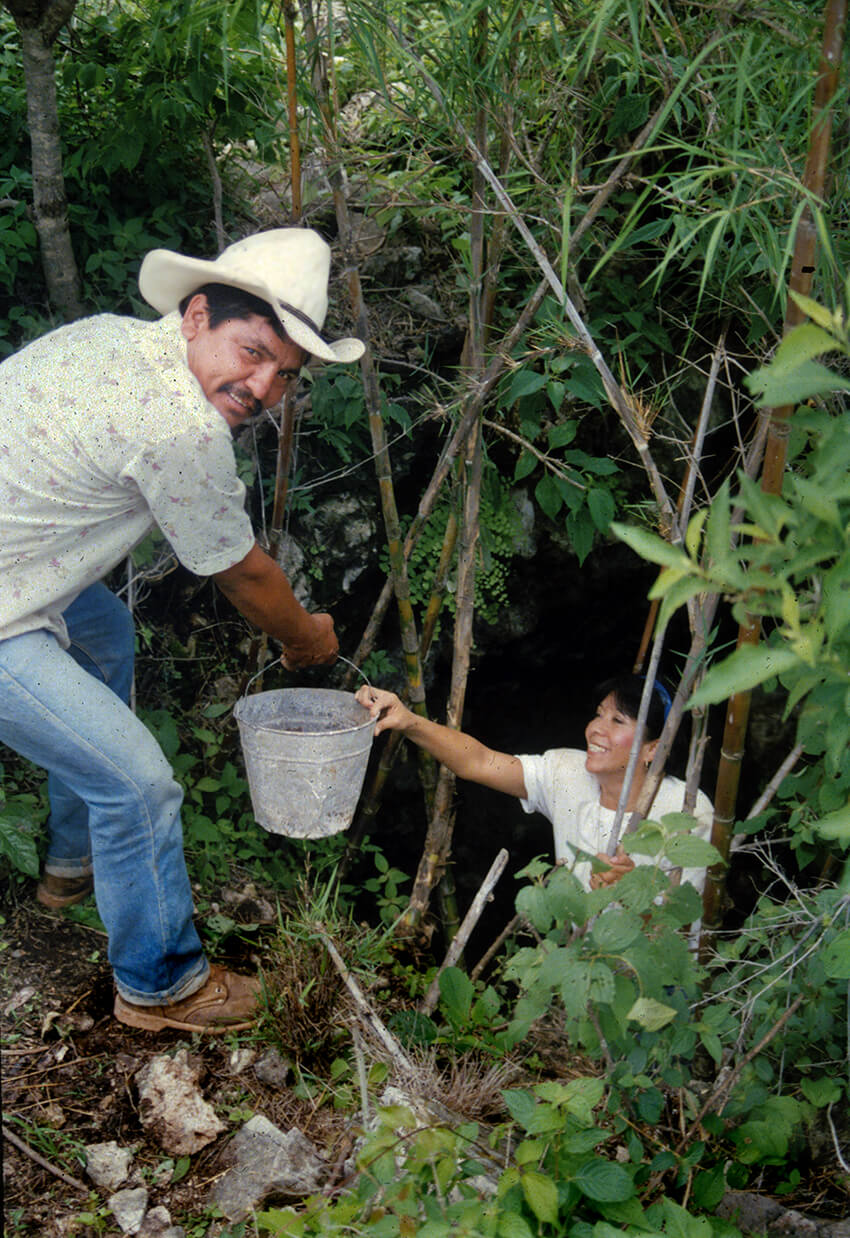

When we left the cave, we removed as much of the first barrier as we could (with Paulo’s permission) but suspected that it would soon be put back in place. Since the cave had no name, we baptized it “La Cueva de Rogelio y Teresa” after the humble couple living in a little cabin nearby who treated us totally unexpected guests to an incredibly delicious hot dinner.

During the long walk back to Ojo de Agua, we came upon a group of men, each with a metal tank strapped to his back. They were fumigating their crops. They saw our helmets, and we told them that we had been exploring the big cave up the hill.

“We checked every inch of that cave and never found the slightest sign of vampire guano,” I told them. “Those were insect-eating bats in there, and now you people have to spray your crops with poison to keep down the bugs.

“If there’s treasure in that cave (I said with a glance at Paulo), it’s the tons of good fertilizer lying on the floor. But, of course, somebody has killed off the bats that make the fertilizer. Why would anyone put up a barrier against helpful murciélagos that eat bugs and pollinate plants?”

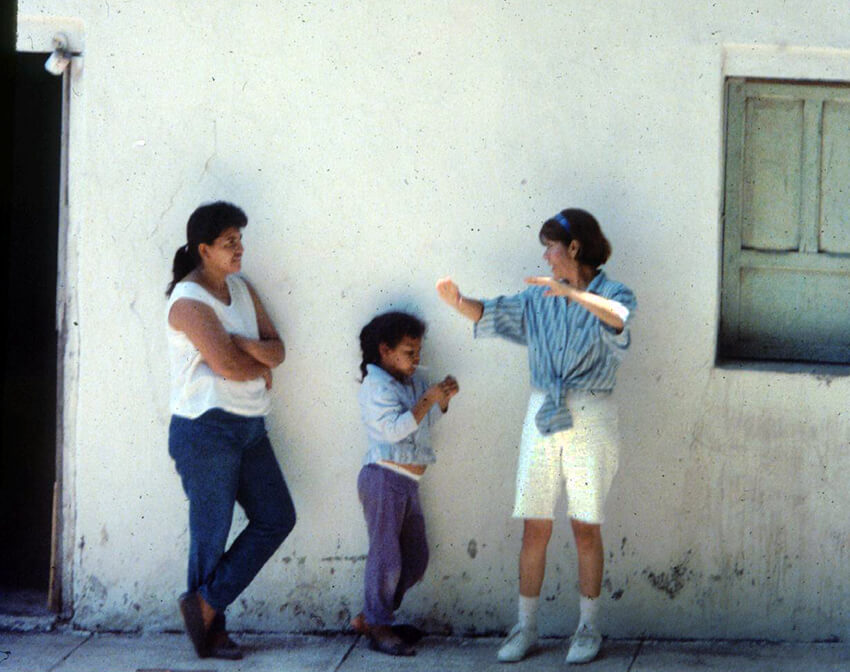

That night, in Ojo de Agua, we put on a slide show made by Bat Conservation International. To our surprise, just about everyone in the rancho and the neighboring pueblito of Coatlancillo showed up and the keenest questions came from a little old lady who could barely walk.

Several months later, we were back in Ojo de Agua with survey equipment to map the cave. Once again, we were heading up the steep, narrow trail but this time riding horses and mules that “might come in handy for carrying back the treasure,” according to Paulo, the eternal optimist.

Equestrian caving is definitely for me. Instead of arriving pooped out, we reached the entrance in high form, raring to go.

Later, in the course of mapping the cave, we received two wonderful surprises: first, the local people had apparently believed us city slickers and had actually ripped aside three of the four chicken wire barriers.

Second, when we walked into the guano passage, we were greeted by hundreds and hundreds of flying creatures! There were so many swirling around us and bumping into us that we had to crouch on the ground and wait several minutes for them to get used to our presence. The bats were back!

Our visit to Ojo de Agua took place several years ago. Today, thanks to the work of people like Mexico’s Bat Man, Rodrigo Medellín, the kind of people in Mexico who watch documentaries can now make a distinction between insect-eating and pollinating bats and blood-feeding vampire bats.

Whether the news has reached the ears of people who live in those remote spots where caves abound, I’m not so sure. Years ago, I suggested that radio spots about bats be placed on those ranchero music stations that can be heard even in the middle of nowhere.

All a rancher needs to know is how to distinguish between the guano of vampire, insect-eaters and fruit bats. After that, he can figure the rest of the story out by himself.

Once again, I repeat the call for radio spots, because today we need bats more than ever.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.