A Zapotec priestess named Yezari loses her powers of divination after giving birth to her daughter. As Yezari seeks to recover her abilities, she dreams that she becomes a mountain lion.

Terrified, she tries to scream. Instead, she lets out the roar of the big cat in an onomatopoeic expression that is its name in the indigenous Sierra Zapotec language: “Nkui nkuau, nkui nkuau.”

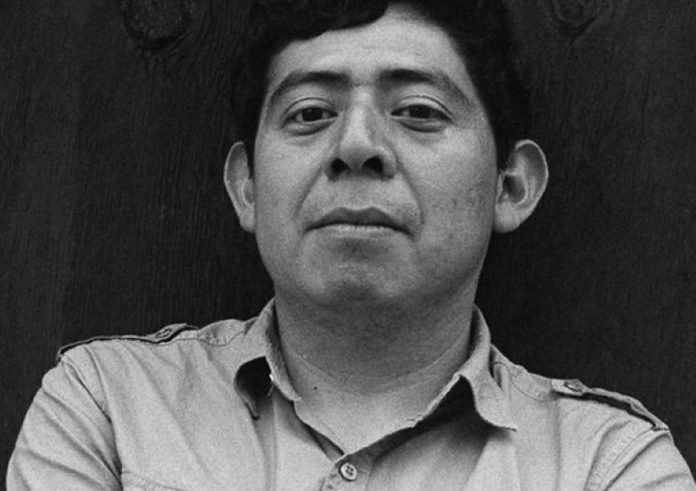

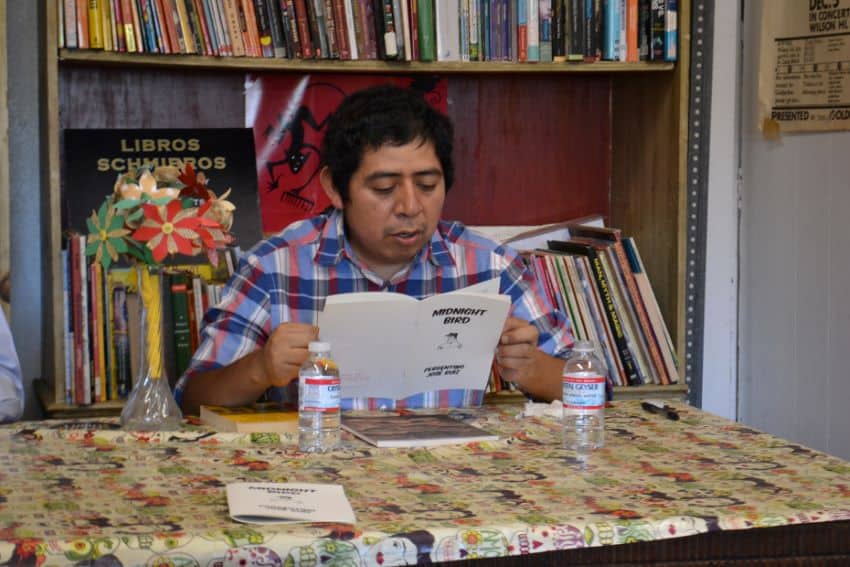

This is part of the plot of “The Priestess on the Mountain,” a short story in the collection Hormigas rojas (Red Ants) by Zapotec writer Pergentino José.

Published in English by Deep Vellum Press, the collection represents a groundbreaking step: it is the first literary translation by a publisher of Sierra Zapotec fiction into English.

“I think there is a great vitality in the Zapotec way of thinking, a unique way of thinking about things that have been very little appreciated, because in general there has been scant dialogue on how reality is thought about from an indigenous language,” José said.

Sierra Zapotec is José’s mother tongue, and he is a champion of keeping Zapotec languages alive. When he worked for nearly a decade as an elementary school teacher in San Agustín Loxicha, Oaxaca, he translated books for children into his language and often visited K-12 schools to talk to children about Zapotec culture.

He uses the expression yanayee, yanabànd — a tree that is green, a tree that is alive — to denote what he calls a Zapotec way of thinking about life itself.

For José, Sierra Zapotec reflects a vast oral tradition, including storytelling, and he writes fiction in his mother tongue to channel this orality.

A challenge, he said, is conveying the Zapotec culture’s orality through written Spanish. Yet this intersection represents his work’s starting point.

The stories in Red Ants are set in the Oaxaca highlands, where José was born in 1981 in a Zapotec village. He has gone on to a career of achievement in literature, including being published in the México20 anthology honoring the country’s top young fiction writers, while earning membership in a government-run fellowship program for writers and artists, the Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte.

His influences include writers Juan Rulfo, Franz Kafka, the Japanese novelists Junichiro Tanizaki and Dazai Ozamu and the Argentine writer Ernesto Sabato.

His next upcoming book involves the duality between an actual Zapotec town named Quelobee, the setting of some of the stories in Red Ants, and its fictional urban counterpart, Tepexipana.

For the cover, Deep Vellum is seeking to acquire the rights to an image by the late Mexican artist Martín Ramírez, a migrant who was confined to a psychiatric hospital in California.

Ramírez did all his paintings from the hospital, and his collective work, José said, “shows … the descent into the underground and the alienation that results from being transplanted into a different culture.”

Some of Red Ants’s stories were originally written in Sierra Zapotec, and others were originally in Spanish. All were written between 2009 and 2011 and originally published in the journal Almadia of Oaxaca in 2012. In Deep Vellum’s collection, the stories were translated by London-born writer Thomas Bunstead.

The challenge of translating Zapotec into English was augmented by the stories’ stylistic approach. They have been described as magical realism, but for José, something else is at work:

“In my stories, there is not magical realism. What exist in my stories are atmospheres, spaces of indetermination, stories that take the structure of a dream, something close to the oneiric,” he explains.

He notes that one such story, “El témpano,” was particularly difficult for Bunstead to translate. In this story, all that the reader is left with is the facade in which a long wait transpires.

A stream of Sierra Zapotec names, places and expressions flows through the stories.

In “The Priestess on the Mountain,” the main character Yezari has a Zapotec name, while the city priests pray and sacrifice to two Zapotec swamp gods, Mbdan and Mbsiand.

In “Room of Worms,” a Zapotec expression is used to describe workers destroying bamboo trees on a coffee plantation — “the murmur of people moving closer, ñee mend mbchas mbii mend, as though they were floating on the air.”

When José uses a Zapotec expression in a story, he follows with its translation. “[If] the conversation continues in Zapotec without a translation, this would simply disappear from the comprehension of the reader,” he said.

His characters are heirs to an indigenous culture rooted in the natural world, but their customs and language are at risk.

Relocating to urban housing is offered as an alternative to their traditional lifestyle, but it disconnects them from nature while introducing threats such as unemployment, violence and exploitation.

In “Room of Worms,” for example, the coffee plantation workers cut down the bamboo because the owner, Don Elpidio Alonso, decides only to grow coffee trees.

Although Don Elpidio has not paid his workers in some time, they are so eager to complete the job that they enlist children to help. They hack away with machetes and burn the bamboo, startling the birds and butterflies.

The titular story “Red Ants” also involves arduous work on a coffee plantation. A woman named Georgina Navarro spends a day collecting coffee beans with her young daughter, Lubia, who only speaks Zapotec. They do the work in a driving rain, and all they have to protect them are plastic bags that the owner gives them to wear. Gnats assail Georgina, she loses track of her daughter and things take a mysterious turn when the narrator later encounters Georgina in a courtyard.

José uses imagery of chairs, ferns and thorn-covered creeping vines in the courtyard to symbolize the characters’ desperate life.

“This allegory represents the reality of marginalization and exploitation in which indigenous communities live,” José said.

As José explains, red-colored ants symbolize ill fortune and the inevitability of death in the Zapotec cosmic vision, while yellow ants represent long life. Zapotec children try to capture and keep them in matchboxes for good luck.

In the titular story, red ants swarm the chairs, ferns and vines of the courtyard where the narrator goes in search of the missing Georgina.

“[Because] the stories speak of abandonment, mothers who have lost their children, broken agreements, long waits and rupture [caused by waiting], it seemed appropriate to call the book Red Ants,” he said.

The ill fortune these ants symbolize is present throughout the collection, including in José’s favorite story in the book — “Threads of Steam,” in which the protagonist participates in a fake employment agency that is actually a kidnapping ring preying on the unemployed.

“There is an intention, aesthetically and through social criticism, [to address] the problem of unemployment in Mexico, and an even more serious problem — disappeared persons in the country,” he says of the story.

Although José said that “Threads of Steam” reflects a stylistic distancing from the themes of the other stories in the book, he sees commonalities across his characters.

“My characters are on a continual search,” he said. “They have all lost something. These characters show themselves through literary fiction to be part of a world shaken by violence, heartbreak, certain rules of the Zapotec gods to which they have submitted themselves.”

He calls his characters “individuals embodied by hopelessness, facing the state of being spiritual orphans, living in an upheaval in which they cannot speak their mother tongue.”

Now, English-speaking audiences are getting a chance to learn about the Sierra Zapotec language and the wider culture it represents.

“The book has had a good reception,” José said. “It has created expectations that it is possible to write in an indigenous language while complementing it with the Mexican literary tradition.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.