It was all over the news in Mexico on Tuesday: more than 100 countries had signed an international pact against deforestation, but Mexico was not on the official list.

A few hours later, however, a new list was released, this one signed by Mexico but apparently at the last minute and, according to some observers, only because of pressure by environmental groups.

Adding to the mystery of the affair was the fact that clarification of Mexico’s having signed the Glasgow Declaration at the COP26 climate change conference in Scotland came from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, rather than the Ministry of Environment, whose minister was still in Mexico at the time.

At his morning press conference on Wednesday, President López Obrador questioned how Mexico could not possibly have signed an agreement which he claimed was inspired by his reforestation program Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life).

“Where do you think [the deforestation accord] came from? From Sembrando Vida; they said that Mexico didn’t sign onto the reforestation program … we proposed [it],” the president said, observing that it is “the most important reforestation program in the world,” adding, “There’s no other country in the world that is investing $1.3 billion a year in reforestation.”

López Obrador also thanked Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard for representing the country’s interests at COP26 — even though he wasn’t there. The president appears to have confused the climate conference with last weekend’s October G20 summit of world leaders in Rome, which the foreign minister did attend, where he pleaded for funds to help developing countries address climate change.

Environmentalists criticized both the nation’s tardy acceptance of the reforestation accord and the president’s Sembrando Vida project.

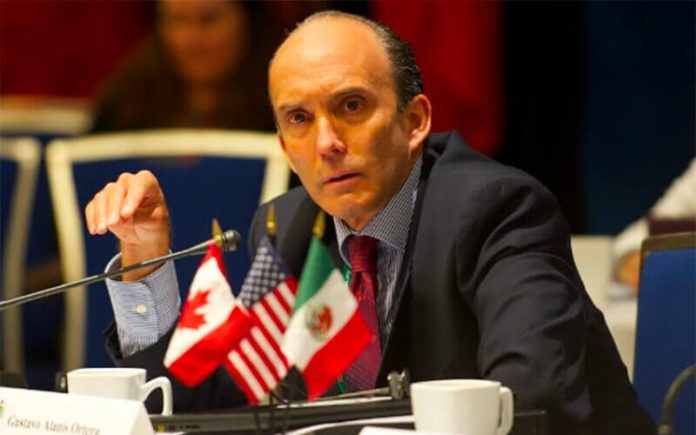

The president of the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA), Gustavo Alanís Ortega, called the president’s statements a “flight of fancy,” saying that Mexico did not sign the reforestation accord until pressure from the domestic and international environmental community forced them to.

Alanís said the president’s tree-planting program has in fact caused tens of thousands hectares to be deforested, according to information from the World Resources Institute. He also called the government’s request for climate change funds hypocritical given their policy record.

“There’s a very strong contradiction in Mexico asking for those resources and building a refinery, promoting carbon-based electric plants and with the electricity reform it is promoting the use of fossil fuels,” Alanís said. “With the Maya Train they are deforesting, with the Dos Bocas refinery they illegally cut down at least 80 hectares of mangrove and with Sembrando Vida they have deforested 72,000 hectares, so they are not being consistent. We are simply talking about yet another flight of fancy of the president of the republic.”

In the Glasgow Declaration, more than 130 countries agreed to reverse current deforestation trends by 2030. Even “climate rebels” including Brazil, Russia and China agreed to the accord, which some environmentalists criticized for its lack of ambition. Greenpeace, for example, called the 2030 deadline for change a “green light for another decade of forest destruction.”

With reports from Reforma, Expansión Política and Animal Político