We have been in the process of renovating our recently acquired pile of bricks for three weeks as of this writing. All of our truly disruptive demolition has taken place over the past three weeks and real construction has begun.

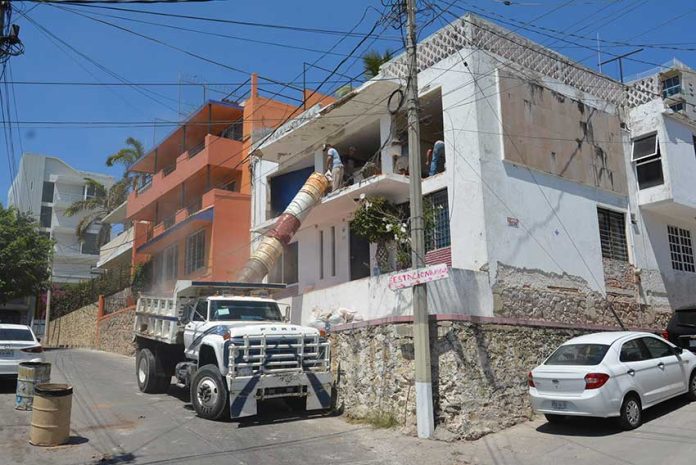

Of the three original laborers, two remain and have been joined by two more. Their capacity for pure destruction is admirable. So far, we have removed three, dump truck loads of rubble and have another two to go.

I utilized tarps and duct tape to erect curtains between the demolition and the still livable portion of the house. This technique is capable of eliminating 95% of the dust generated by concrete saws and rotohammers. However, even with the best of dust prevention measures, the 5% that finds its way into the living space is substantial.

After work the other day, I went to the refrigerator to retrieve a cold beer. When I pulled it out, something did not look quite right. Upon closer inspection, I realized it was the only thing I had seen all day that did not possess a layer of fine dust.

Fortunately, The Captured Tourist Woman fled to Australia after the first week of major demolition and will return when her fine counsel will be required for the installation of the finishes.

By the second week, it was time to start building new interior concrete block walls. The albañil (mason) showed up on Monday morning ready to lay block.

Concrete block has been around for over 100 years and has been used in Mexico for the last 50-plus years. In this area of Mexico, the block is used as a brick replacement and simply serves as infill between reinforced concrete castillos (columns) and dalas (beams).

In other parts of the world, concrete block is used as the manufacturer intended, as a CMU or concrete masonry unit. With a typical CMU the block cavities are filled with reinforcing steel and concrete and the wall becomes a structural component capable of carrying the load of a multi-story building.

On my first morning briefing with our new albañil I explained the process of building a CMU with just a bit of trepidation. My experience with several other albañiles had shown me that many tradespeople will only perform work in the same manner as their father or grandfather or uncle, or whomever they learned from.

I know there are trade schools throughout Mexico, but I have only come across one of the graduates in the last 12 years.

When the albañil said he had no problem putting the concrete and steel in the block cavities, I put my hands in the air, and exclaimed, “Halleluiah.” The ancient Aztec gods of construction have certainly smiled down upon me.

I knew that later I would need to make a sacrificial offering to properly demonstrate my gratitude. The yappy chihuahua next door would fit nicely on the stone altar.

My albañil is 32 years old and learned his trade from his father, but had spent a lot time laying block the Mexican way. He was more than willing to place steel and concrete inside the blocks, and expressed his opinion that it had always seemed to be the proper way to use concrete blocks.

After hearing this, I knew I needed to find a second chihuahua.

By the third week of the project, his father became our second albañil and we began the process of replastering the north wall of the house. When I wheeled out the air compressor and the stucco sprayer, they were ready to take their skills into the 21st century.

I had purposely started on the north wall of the house because it is the least visible of the exterior walls. Since I am mixing color in the last coat of plaster, the north wall gave me a large canvas to hone the new procedures.

Just so there is not any confusion about cementitious coatings, I need to interject a brief explanation. In the countries north of the border, stucco is the cementitious coating applied to the exterior of buildings, while plaster is the proper term for the same type of coating, but on the interior walls.

In other words, stucco and plaster are the very same thing. But since I am in Mexico, I will call it plaster, no matter how or where it’s placed.

Our two albañiles are working with one peón and have mastered the spray and then trowel method of plastering.

When I asked the younger albañil his opinion after the first day with the sprayer, he thought for a minute and then responded, with a big smile. “A toda madre,” which I am told is Spanish for “It’s really swell!”

In my next installment of this continuing saga, we will explore the wonderful and wacky world of residential electrical systems in Mexico.

The writer describes himself as a very middle-aged man who lives full-time in Mazatlán with a captured tourist woman and the ghost of a half wild dog. He can be reached at buscardero@yahoo.com.