What do carnitas – pork simmered for hours in its own lard – and an ancient Mayan stone tablet have in common? Apart from their shared mexicanidad, or Mexican-ness, not much, one might think.

But the two are inextricably linked in the discovery of the long-lost capital of an ancient Mayan kingdom in the southern state of Chiapas.

In June 2014, Whittaker Schroder, then a grad student at the University of Pennsylvania was touring archaeological sites in Chiapas looking for inspiration for a dissertation topic when he saw a carnitas vendor waving at him on the side of a highway in Ocosingo near the border with Guatemala.

Believing that the vendor was encouraging him to buy some tacos, and being a vegetarian, Schroder continued on his way. However, the day before he was leaving Chiapas, the student saw the same man in the same place waving at him again.

This time, Schroder, who had been visiting the same area for years, pulled over.

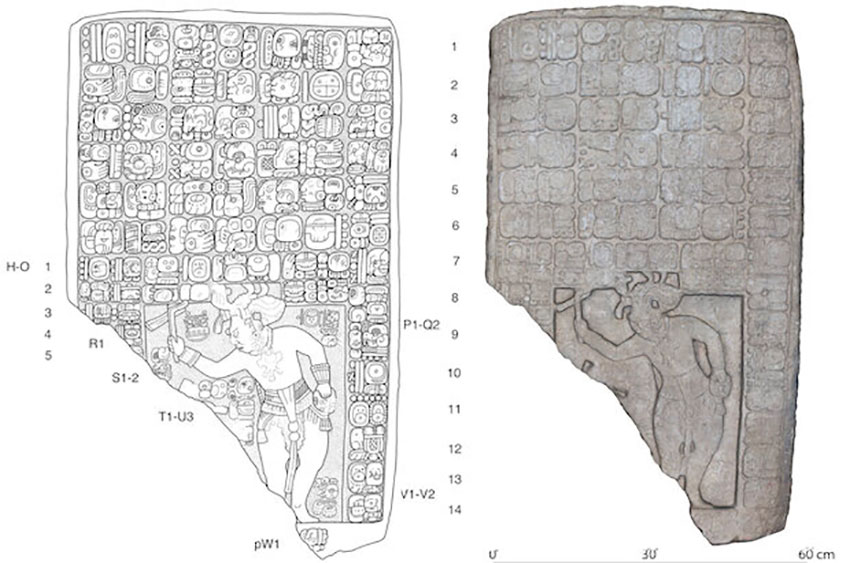

The carnitas vendor, it turned out, wasn’t interested in selling any of his succulent pork but instead wanted to alert the student – who he knew was interested in Mayan history – to a discovery made by his friend: an ancient stone inscribed with stories of rituals, battles, a mythical water serpent and the dance of a rain god.

The following day, Schroder and another grad student, Jeffrey Dobereiner of Harvard, met the vendor’s friend, a cattle rancher, convenience store owner and carpenter, who showed them the Mayan stone.

Schroder would later tell Charles Golden, an associate professor of archaeology at Brandeis University, and Andrew Scherer, a bioarchaeologist at Brown University, about what he saw, prompting them to hatch a plan to excavate the site where the stone was found.

It took them years to get permission but along with a team of researchers from Mexico, the United States (including Schroder) and Canada, they began excavating the site – the backyard of the cattle rancher – in June 2018.

What they discovered amazed them – the ancient capital of the Sak Tz’i’ Mayan kingdom. According to a report published by science and technology news website Phys.Org, academics have been looking for evidence of Sak Tz’i’ since 1994.

Named Lacanja Tzeltal after the nearby community, the site discovered by Golden and Scherer was likely settled by 750 B.C. and then occupied for more than 1,000 years.

As a result of excavations, the archaeological team has found remnants of pyramids, a royal palace and a ball court as well as a treasure trove of Mayan monuments. The team has also found remnants of fortifications believed to have been built to keep out invaders.

Sak Tz’i’ – which means white dog, although for what reason is unknown — was far from the most powerful Mayan kingdom, and the structures that once stood in its capital are very modest when compared with the pyramids of such sites as Palenque and Chichén Itzá.

But Golden says that the discovery still contributes a lot toward a greater understanding of ancient Mayan culture and politics. It’s a “big … piece of the puzzle,” he said.

He and his collaborators published the results of their research in the December edition of the Journal of Field Archaeology.

Pending permission from the Mexican government and the local community, the archaeological team plans to return to the Sak Tz’i’ capital in June to continue mapping the ancient city using the laser surveying method known as lidar (light detection and ranging).

They also intend to stabilize ancient structures that are in danger of collapsing, carry out further studies of sculptures and other monuments found at the site and explore an area believed to have been a marketplace.

Golden said that the team will seek to continue working closely with members of the local community, many of whom are the descendants of the builders of pre-Hispanic Mayan cities.

“To be truly successful, the research will need to reveal new understandings of the ancient Maya and represent a locally meaningful collaboration with their modern descendants,” he said.

Source: Phys.Org (en)