I moved to Mexico the same year as ex-president Felipe Calderón began his disastrous war on drugs, in 2006.

That year, the murder rate for the state of Sinaloa was 22 people per 100,000. Just the year before, it was only eight per 100,000. (The United States has five per 100,000.) By 2011, it had jumped to 50.

Mr. Calderón’s actions fragmented the cartels from three major criminal organizations, which had been somewhat organized and stable, into a full-blown free-for-all.

For several years afterward, full-color pictures of men and boys with ventilated craniums and with thumbs wired behind their backs were plastered across the pages of the local rags every single day. Just standing in front of a local newsstand and perusing the front pages was not for the faint of heart.

The Zetas — a spinoff of the Gulf Cartel that happen to be the most vicious of the cartels, offering murder for hire, extortion and kidnapping in addition to their drug business — were challenging the Sinaloa Cartel throughout western Mexico.

Here in Mazatlán, there were shoot-outs in the colonias (residential neighborhoods), executions in several cantinas and shootings in nightclubs, along with the daylight murder of a Mexican man directly in front of gringo tourists at a popular hotel. At this point, even the expat community was nervous, and many did not venture out at night.

In 2011, when Calderón came to town to assure the general population that he was doing his best to kill or capture the bad guys, he was greeted with a large banner erected in the plaza where he was due to speak. It simply said: “Mr. Calderón, leave the Zetas to us.”

By the following year, the Sinaloa Cartel had eliminated the threat of the Zetas in western Mexico. Of course, at the end of that year, the body count was approaching that of a central African nation after an election, but things felt safer.

During these troubled years, all the Anglo news services were slamming Mexico like a screen door in a hurricane. Month after month, for almost four years, the Canadian and the United States state departments were issuing dire travel warnings about Mexico: don’t go — you’ll die.

Ten years ago, the excessive carnage in Mexico was due almost exclusively to bad guys whacking bad guys. When I wrap what’s left of my mind around this concept, I ultimately think I’m OK with it; let them kill each other.

I know that a few people who are not targeted will die, but for the most part the narcos were fairly selective with their exterminations, very much unlike Detroit or south central Los Angeles, where a kid could get shot for his tennis shoes. (I have often wondered why they don’t issue travel warnings for certain U.S. cities where random violence is not uncommon.)

However, as capture nets were flung far and wide by law enforcement, cartel members scattered into splinter groups and began forming their own criminal cartels. Soon, besides drug cartels, there were avocado-stealing cartels, gasoline- and diesel-stealing cartels, extortion cartels and human trafficking cartels. Carjacking has also increased, but unlike carjacking in the U.S., here in Mexico the passengers are rarely harmed.

Lately, several of the newer and more vicious cartels have begun to kill entire families, as well as reporters who have written unflattering anecdotes about their activities. The violence is also more widespread but is still always connected to some type of criminal enterprise.

The unfortunate consequence of this ill-conceived war on drugs has been to violently stir a seething cauldron of greed and corruption. When you have an activity that generates US $35 billion to $50 billion each year, there is no hope to control it, and the idea of stopping it is pure fantasy.

One school of experts tells us that the only way to make it disappear is to eliminate its lucrative nature; take the money out. But all views concede that while the legalization of all drugs would likely end the drug wars, it would also unleash a horde of newly unemployed criminals upon society. The displaced narcos would have an extremely limited set of skills, most of which fail to contribute to the common good.

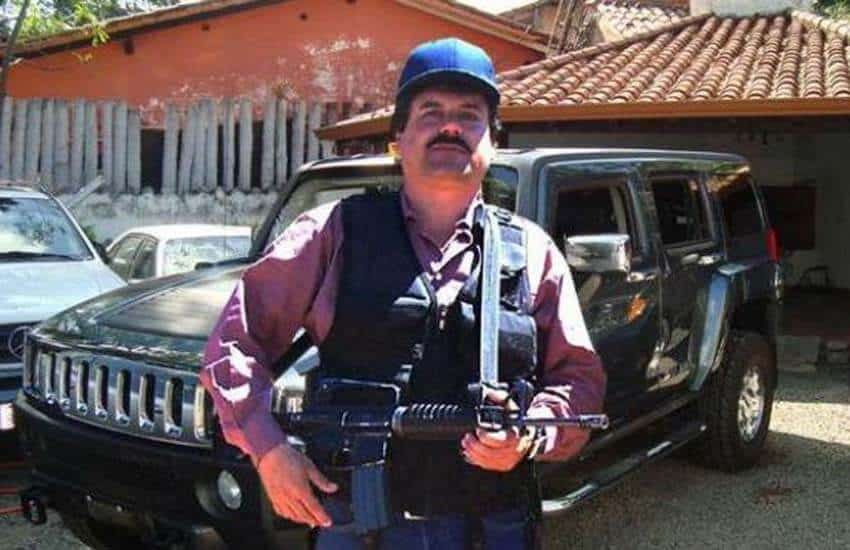

So, what does all this mean for those of us who live here? I have always felt safe living in Mexico, even during the worst years of the violence. But how do you convey your sense of safety to friends and families who think El Chapo is your next-door neighbor? Do we need to run out and get Kevlar vests and armored vehicles? “Barricade the condo, Mabel, the narcos are storming the gates!”

The simple answer is that those of us who live here cannot adequately express our feeling of personal safety to someone who has never been in the country. Most people north of the border equate the violence in Mexico as similar to that of the worst of the urban areas in the U.S. but with a higher body count. But the difference between the two is the random nature of the bloodshed in the United States. Here in Mexico, post offices are not free-fire zones and school shootings are nearly nonexistent.

This does not mean that as an expat you are safe from any type of criminal encounter; it’s just that you stand a far better chance of surviving one in Mexico.

However, I still have a few friends in the States who think I am going to be gunned down any day now. I don’t mean to downplay the violence and corruption, but criminal cartels are now a part of life in Mexico — and will be for the foreseeable future.

I believe that all the expats who live in Mexico have their own set of guidelines for steering clear of the criminal elements; I know I do.

For example, gone are my days of handling large amounts of cocaine or bales of pot. I have also given up my opium smoking and no longer make rude hand gestures to SUVs with blacked-out windows.

So, always be aware of your surroundings and act accordingly. We are still better off here than in urban areas of the U.S.

(Note: Bodie Kellogg was kidnapped two weeks ago. Last week, his captors raised their offer to 10 cases of Pacífico to anyone who will come and take him off their hands.)

The writer describes himself as a very middle-aged man who lives full-time in Mazatlán with a captured tourist woman and the ghost of a half-wild dog. He can be reached at buscardero@yahoo.com.