I understand the need to create a national identity in order to recover from a decade of bloody internal war. In the wake of the Mexican Revolution, promoting a nascent nationalism was no doubt a useful response to the recent and blatant violations of Mexico’s sovereignty. I get it.

But when a guy starts talking about the superiority of his race, that’s when I reach for my laptop.

The guy in question was José Vasconcelos, Mexico’s top public intellectual of the first half of the 20th century. In his work, Vasconcelos assigns Mexicans to a “cosmic race” which represents no less than “the fruit of all the previous ones and amelioration of everything past.”

Just what the membership requirements are for this dream team of a race are lost in a contradictory discourse that cites native values as its core principle even while calling for the dilution of indigenous traditions in the service of a Pan-American mestizaje.

Still, injecting race into the nationalist project effectively recruited the entire population to the cause of protecting Mexico’s sovereignty, whether it was actually threatened or not. From then on, any potentially invasive act or comment by a foreign member of an insufficiently cosmic race was not just a violation of your nation’s political sovereignty, but an affront to you personally, an attack on your very identity.

We can roll our eyes today, but Vasconcelos was by no means the only advocate of a racialized approach to sovereignty in his time. He was, however, the only one whose day jobs included minister of education, rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and director of the National Library of Mexico. It was from these perches that he inserted his ideas into the national curriculum, bequeathing words like raza and soberanía a special prominence in the political vocabulary to this day, and guaranteeing future presidents plenty of public support whenever they might play the sovereignty card.

“I think it has a lot to do with the way that Mexicans have been educated, myself included,” Denise Dresser, the bilingual Mexican columnist and commentator, said recently during an Americas Quarterly podcast. “Decades of an official narrative . . . all of the history books that were read by children, all of the speeches, even the iconography, are all based on the idea of the protection of sovereignty.”

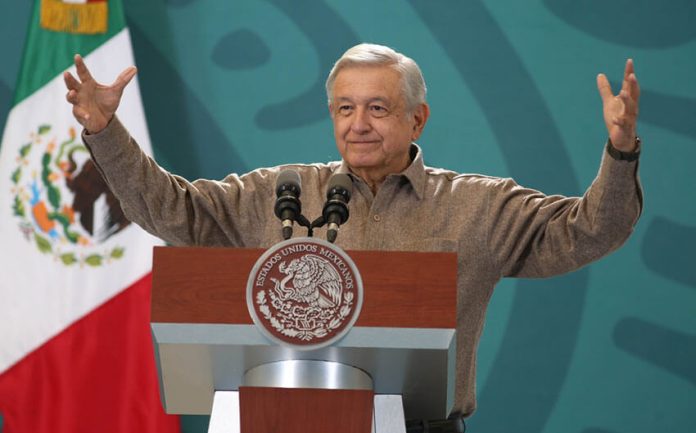

Fast forward to 2022, when Mexico and its two northern neighbors are carrying on a spat that could get ugly. The United States and Canada are challenging the current administration’s moves to semi-renationalize (to coin a term) the energy industry as a clear violation of the USMCA, the successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement, which guarantees a level playing field in electricity investment. That challenge, in turn, is seen by the López Obrador administration as a clear violation of Mexico’s sovereignty. Guess which position went over best with the public.

If you’ll forgive a stretched metaphor, President López Obrador played the sovereignty card in spades. Instead of quoting language in the USMCA that may support his argument, he launched into a greatest hits of time-honored grievances, including “we’re not a colony anymore” and that he’s “nobody’s puppet.”

U.S. and Canadian negotiators have surely learned to ignore nationalist noise, and even the Mexican press, once reliably on board with any accusation of violated sovereignty, isn’t buying it. In researching this article I had a hard time finding many media dissenters from the consensus opinion that the administration’s rhetoric is not only manipulative and irrelevant, but actually weakens the cause of sovereignty by jeopardizing Mexico’s credibility as a trading partner.

None of that matters. The president’s message wasn’t meant for President Biden, or Prime Minister Trudeau, or the USMCA interpreters, or the media. The target audience was the Mexican people. The motive was to galvanize his supporters and warn his adversaries that their refusal to defend Mexico’s sovereignty will be seen as traitorous behavior.

And – surprise, surprise – it worked. His support is strong. The sovereignty card has plenty of legs left in it. And President López Obrador, despite the impression left by the chattering classes, remains popular.

It should be made clear that the United States is no green angel here. Support from progressives for keeping private investment alive in the energy sector may seem out of character, but it’s seen as the shortest path to renewable energy — wind, solar, geothermal. However, that’s not the motive for the complaint. U.S. and Canadian corporations see the USMCA as guaranteeing them a piece of the Mexican energy action and they damn well want their share.

And, of course, U.S. politicians, mostly conservative, are themselves not above citing sovereignty when it suits them. It has suited them, for example, when justifying jailing children, tossing innocent asylum seekers back across the border to fend for themselves, implementing blatantly bigoted immigration rules and blocking international courts from sniffing around too close to home.

Strictly speaking, the USMCA does in fact chisel slightly at Mexican sovereignty in terms of energy policy. Any trade pact asks the signatories to cede some power for their mutual benefit. The parties go into the deal with their eyes wide open and agree to its provisions. That’s why they’re called agreements.

Mexico signed on to the USMCA as a co-equal partner (as opposed to a puppet or a colony) on López Obrador’s watch. Predictably, he’s taken a lot of razzing for labeling a document that he endorsed as being in violation of his country’s sovereignty – an own-goal if you will. But rolling back his predecessor’s energy privatization is a high priority for this president. He’s not going to give that up easily.

It’s sad that Mexico’s legitimate concern for protecting its sovereignty is so often hijacked for stirring up the masses. Mexico’s nationalist stance does not necessarily rule out resorting to a negotiated solution that the treaty provides for settling these disputes. It could just mean that Mexico gets a multimillion-member cheering section during the amelioration process. It’s possible that everyone can come out of this happy, however grudgingly.

But if Mexico decides to go to the mat and loses, observers say the consequences could be serious. Punitive tariffs would hurt the Mexican economy in ways that average residents will feel. The USMCA itself could be scarred, or worse. So might Mexico’s relations with the United States.

Kelly Arthur Garrett has been a reporter and columnist in Mexico since 1992.