The Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) overcharged 27,000 customers by nearly 142 million pesos between 2011 and 2018.

During the eight-year period, the CFE received just over 223,000 complaints from customers who claimed that billing for their power consumption had been excessive.

The commission has investigated 55% of the complaints and found that in 27,412 cases, customers’ bills were indeed higher than they should have been.

The excessive charges totaled 141.99 million pesos (US $7.5 million at today’s exchange rate) – 40% higher than they should have been – but with 45% of cases still unresolved, that figure can be expected to increase significantly.

One of the reasons why the CFE overcharges customers is that in some cases it calculates bills by estimating consumption rather than by checking meters.

According to the Federal Auditor’s Office, just under 3% of bills are based on estimates, and the practice has been particularly prevalent in parts of central Mexico, including the capital, where the now-defunct state company Luz y Fuerza del Centro once operated.

The CFE told the newspaper El Universal that in all cases where billing errors are detected, electricity rates are adjusted and customers are compensated.

But for some consumers, the commission’s recognition of its mistakes either came too late or they are still waiting for their complaint to be investigated. People in both situations have been forced to close their businesses.

One such person is a 62-year-old man identified by El Universal only as Sergio.

For more than a decade, Sergio worked as a grocery store employee but lost his job in 2003 after which he used his severance pay to set up a small store in southern Mexico City.

The main consumers of energy in his tiendita were two fridges, two large lights, a refrigerated display case and a deli meat slicer.

During his first decade as a small business owner, Sergio never paid more than 2,500 pesos (US $130) for his electricity use during a two-month billing period.

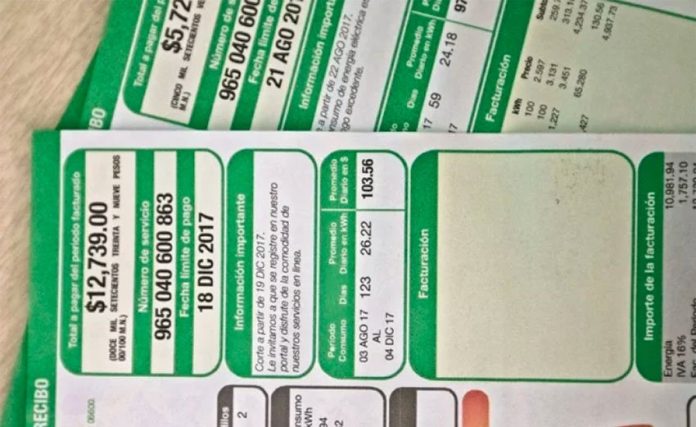

But in 2012, the bills unexpectedly began to rise, showing charges of 5,000 pesos in some cases and 7,000 pesos in others.

In October 2015, Sergio’s electricity bill hit a high of almost 15,000 pesos, six times the maximum amount he paid between 2003 and 2012.

For three years, Sergio allocated the entirety of his profits to paying his electricity bills but with his business’s ongoing survival under threat, he filed a complaint in 2016 with the federal consumer protection agency, Profeco.

Profeco officials told Sergio that while his complaint was under investigation he was not obliged to pay his electricity bills, and that in fact if he did it would be interpreted as a sign that he accepted that the charges were correct. Sergio heeded Profeco’s advice.

But it wasn’t long before CFE personnel arrived at his store to cut off the power. The store owner produced the record of his complaint but the technicians disconnected his service regardless.

Sergio managed to get his power reconnected but after it was cut a second time he decided to close his store and sell off all his equipment out of fear that he would run up a debt with CFE that he would be unable to pay.

And so after almost a decade and a half of investing all of his time and significant amounts of money into his sole source of income, Sergio’s business was shuttered for good.

Statistics show that the CFE practice of cutting off electricity supply despite the existence of investigations into excessive electricity charges is fairly common.

The National Human Rights Commission has received 3,042 complaints over the practice since 2010.

While small businesses such as that owned by Sergio have suffered and in some case closed as a result of excessive charges, the CFE attempted to overcharge some industrial businesses by much larger amounts.

One factory in Chihuahua received a bimonthly bill in 2016 for 4 million pesos although it challenged the charge and managed to have it reviewed and overturned.

In addition to being able to use their clout to challenge the CFE, large businesses have the option of abandoning the company altogether.

Since the 2014 energy reform took effect, the number of electricity suppliers in the country has grown to 43, according to the National Energy Control Center.

But none of the private companies that have entered Mexico’s electricity market offers basic power packages to homes and small businesses.

Thus, Sergio and others like him have been forced to stick with the CFE despite its shortcomings, unfair treatment and excessive charges.

With a view to once again being able to open his store, Sergio has joined a committee in southern Mexico City that is lobbying the government to apply a “clean slate” to electricity debt, as the CFE has agreed to for more than half a million customers in Tabasco.

The committee is also seeking the introduction of “social rates” in which economically-disadvantaged electricity customers and owners of small family businesses pay no more than 3% of their income on power bills.

But Sergio is not overly confident of success, at least in the short term, telling El Universal that he believed that any such commitment from the government might only happen at some point in the distant future.

Source: El Universal (sp)