The cost of the Maya Train railroad will be one-third higher than originally anticipated due to a range of changes to the project, according to the federal official in charge of its construction.

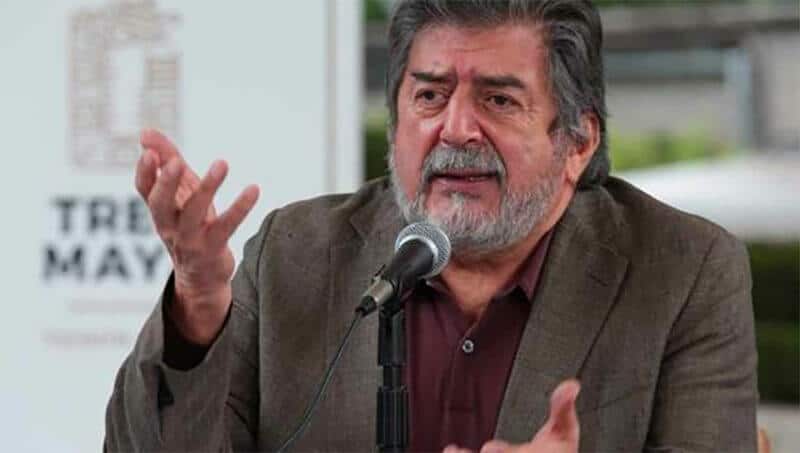

Rogelio Jiménez Pons, director of the National Tourism Promotion Fund (Fonatur), told the newspaper Milenio that the construction of double tracks on half of the 1,500-kilometer route and the electrification of almost 50% of the railroad will increase the cost of the project, which had been estimated at 150 billion pesos (US $7.3 billion).

The total cost is now estimated to be above 200 billion pesos (US $9.8 billion), he said before stressing that the government has sufficient resources to complete the railroad without the need for private investment.

“[The railroad] won’t be more expensive due to minimal reasons but rather because the project will have a better and greater scope,” Jiménez said.

Other changes to the original plan include the construction of a 48-kilometer elevated stretch of track between Cancún and Tulum and modifications to the route in Campeche.

Jiménez said paying for the changes is not a problem because the government’s fight against corruption has generated significant savings.

“Public resources are being released, there are more and more savings and the macroeconomic aspects of the country are sound,” he told Milenio.

Despite the changes to the project and construction delays related to the pandemic, the railroad – which will connect cities and towns in Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo – remains on track to begin operations in December 2023, the Fonatur chief said.

Tourist, freight and regular passenger services will run on the railroad, one of several major infrastructure projects currently under construction by the federal government.

The electrification of almost half the tracks raises initial investment costs but will generate savings in the long term because maintenance costs will be lower, Jiménez said.

According to Fonatur plans, sections between Mérida and Cancún and Cancún and Chetumal will be fully or partially electrified.

Jiménez said the route had to be changed in some places due to archaeological discoveries and other technical issues.

In Campeche, for example, a pre-Hispanic city the size of Palenque was found, he said, explaining that the discovery precludes construction of tracks at ground level. Instead, an elevated section will be built in the area, Jiménez said.

Another change to the project is that the railroad won’t run through the center of Campeche city due to opposition from a group of residents that the government was unable to overcome.

Jiménez said earlier this week that the change will actually reduce the overall cost of the project by approximately 2 billion pesos (US $98.5 million) because it will simplify the project and the government won’t have to rehouse residents who would have been forced to abandon their homes.

However, he acknowledged “it’s a shame” that passengers won’t be able to disembark from the Maya Train and walk to the historic center of Campeche, a UNESCO World Heritage Site surrounded by a wall built in the late 17th century. Under the new plan, the Campeche city station will be a seven-minute drive from the historic center, Jiménez said.

A group of Campeche residents obtained an injunction in March against the forced eviction of people who lived on or near the proposed route. The government hoped to reach an agreement that would allow it to continue with its original plan but was unable to do so. Residents of Ermita, Santa Lucía and Camino Real expressed their satisfaction with the route change on social media.

“The residents … thank our President Andrés Manuel López Obrador for listening to and attending to our request to remove the tracks from our neighborhoods … [due to] the risks the passing of the Maya Train within our beautiful and calm city of Campeche represented. … Thank you for respecting our neighborhoods,” they said.

With reports from Milenio and Obras por Expansión