Mexico is taking steps toward technological independence by developing four Earth observation satellites that could be launched over the course of several months beginning in December 2026.

The satellites, collectively called Mission Ixtli, are being designed to monitor phenomena related to climate change and national security, allowing the country to generate its own information without relying on foreign sources.

Ixtli aims to end Mexico’s dependence on foreign satellite information by using its own technology to generate data and strategies to address forest fires, forest health, landslides, crop health and species monitoring, as well as a variety of national security issues.

Ixtli means “eyes to see” in Nahuatl, the Indigenous language spoken throughout central Mexico.

With a first-year budget of 100 million pesos (US $5.4 million), researchers, students and academics at four institutions — the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), the Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education of Ensenada (CICESE) and the Popular Autonomous University of the State of Puebla (UPAEP) — have been in charge of designing the satellites since December 2024.

A larger budget is anticipated next year so that more domestic technology — perhaps up to 50% — can be included progressively in the design, components, satellite integration and ground stations.

“We want to grow as a technologically independent nation that can make its own decisions,” José Francisco Valdés Galicia, coordinator of the UNAM Space Program, told the news magazine Expansión.

More than 50 government institutions, including the National Forestry Commission, the national statistics agency INEGI and the Environment Ministry, rely on satellite imagery acquired by companies in the U.S., France, and other nations, at an annual cost of roughly 250 million pesos (US $13.6 million).

Valdés said the development of satellites tailored specifically to the country’s needs will help Mexico achieve independence. Additionally, Ixtli will help Mexican scientists gain experience and knowledge in these techniques for the first time, he said.

“The tangible benefits of the project might not be seen for another 10 years,” Valdés said. “But what we will see in concrete terms is that Mexico is entering the space age.”

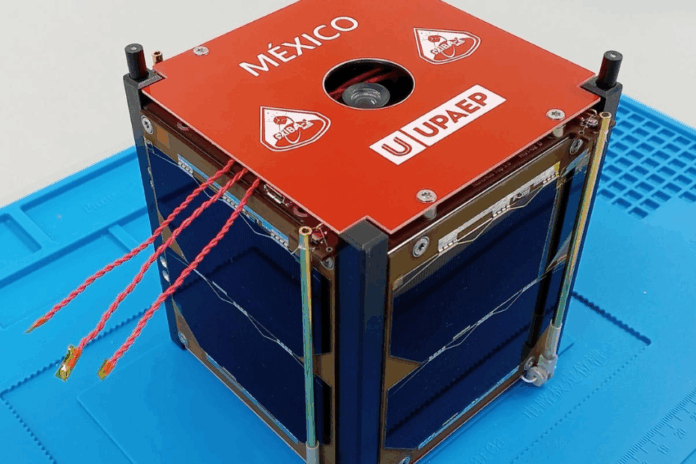

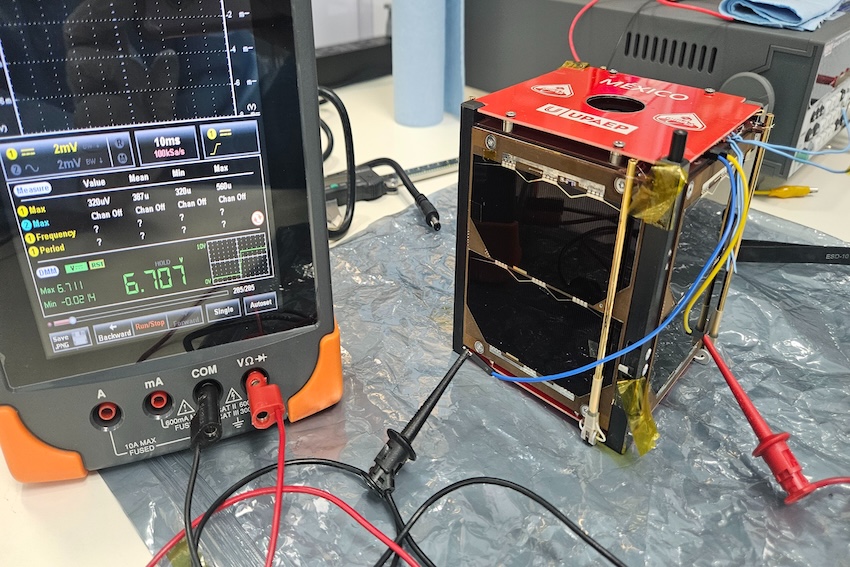

In a related development, the UPAEP will launch its second nanosatellite on Oct. 20. This CubeSat, Gxiba-1 — part of Mission Ixtli — will be launched from Japan’s Tanegashima Space Center and is designed to monitor Mexico’s active volcanoes in the hopes of developing prediction models for possible eruptions.

Gxiba-1 — which means “universe” or “stars” in the Indigenous language Zapotec — is equipped with sensors to measure changes in volcanic gases such as carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

CubeSats typically measure 10 centimeters on each side and weigh approximately one kilogram. They have gained popularity as a viable replacement for traditional satellites in space programs due to their low cost as they can be built with readily available commercial parts.

UPAEP’s first nanosatellite — AztechSat-1 — was launched by Elon Musk’s SpaceX in 2019 and recognized by NASA.

With reports from Expansión, Mundo Ejecutivo Puebla, CarlosMartín.com and La Jornada de Oriente