Five years ago, Rosa Carpio’s youngest daughter was shot in the face by gang members in El Salvador when she failed to make the weekly payment they demanded. After the girl recovered from six months in a coma, Carpio decided to send her daughters, now 16 and 18, to the U.S. with her parents.

Carpio set off a year later to join them. The journey, born of desperation and fueled by hope, swiftly turned into a nightmare.

Along the way, she said, she gave birth to her son, suffered a miscarriage, left her abusive husband, was kidnapped, beaten and raped by Mexican cartel members and saw them kill two women who had been seized with her. She managed to escape, and now she and 4-year-old Geovany have finally made it to the U.S.-Mexico border — only to find it shut.

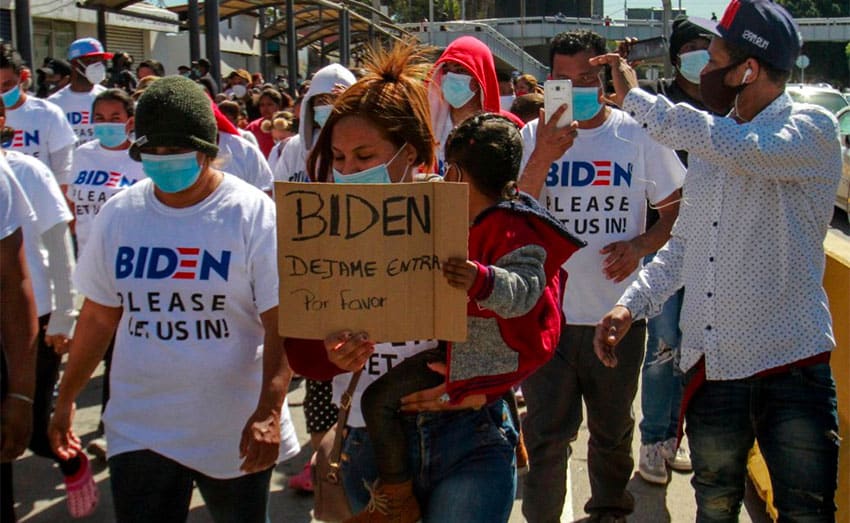

They are among hundreds of migrants camped out in a tent city outside the El Chaparral pedestrian crossing in Tijuana, praying President Joe Biden will eventually let them in.

“I’ve done nothing wrong for all this to happen to me,” said Carpio, 34. “We have faith in God that Biden will let us cross, that there’s a shelter on the other side for us. That’s the only hope we have.”

As things stand, it is a faint one. The only migrants sure of getting across at the moment are unaccompanied children, who have been arriving in near-record numbers in recent weeks.

This has alarmed Republicans in the U.S., who blame the Biden administration for encouraging migrants to attempt dangerous border crossings. Democrats in turn have accused the Trump administration of leaving behind a broken system, while expressing concern about thousands of minors being held in detention centers at the border.

It has also raised the question of how far Mexico will go to help deter what the U.S. says could be the highest migrant influx from its southern border in two decades.

Biden has been rolling back many of Donald Trump’s most controversial zero-tolerance immigration policies, including ejecting children and forcing more than 71,000 migrants to await their asylum hearings in Mexico.

The U.S. said more than 100,000 people tried to cross the border in February. That includes almost 9,500 unaccompanied children, a 62% rise since January and the highest since May 2019, when Donald Trump threatened tariffs on Mexican exports unless it clamped down on migrant flows. The scenes have stirred memories of 2014, when there was also a leap in children traveling solo.

Word that children can get in alone has spread among migrants stuck in Mexico and their families in the crime and corruption-plagued Northern Triangle — Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador — where twin hurricanes last November have increased poverty and desperation.

Norma Claros, a Honduran migrant who has been in Tijuana for two weeks, is now considering sending her daughter Diana, 12, on alone. They had been living in Piedras Negras, 2,000 kilometers away, for two years and tried unsuccessfully to cross into Texas, “but they deported us here.”

“If my girl can go, I’d wait a while here and find a way to get across,” said Claros, 44, who has a brother in North Carolina who could take her in. Diana shook her head furiously.

Experts said Biden’s decision to exempt minors from expulsion will keep the numbers flowing. “It’s a no-brainer,” said Jasmin Singh, a New York-based immigration lawyer.

“It’s all kids at the moment,” said one person in Guatemala involved in the smuggling, or trade.

While the Biden administration has relaxed Trump-era rules on unaccompanied minors, it has kept in place what Sarah Pierce, an analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, called the “draconian” expulsions of migrant adults and families.

“The same day I thought America could change — January 20, 2021 — I was sent back,” said Josiane, a migrant from Cameroon, referring to Biden’s inauguration. While most migrants are Central Americans, there are also Haitians, Africans and Mexicans.

![]()

The estimated 1,500 people in the makeshift camp are in limbo. Many have been in Tijuana for a year or more, trying to get in line to claim asylum. But proceedings were suspended last March because of Covid-19, so they have no way to apply, even if they could cross. And that is proving impossible.

“If you cross unauthorized, you’re usually sent back within two hours, and sometimes in the middle of the night or to small towns — with the excuse of Covid, authorities say they can’t risk having them in their custody too long,” said Savi Arvey, a fellow at the Central America and Mexico Policy Initiative at University of Texas at Austin.

Some families with children under 6 have been allowed in along the eastern end of the border, one of the most dangerous parts of Mexico where 19 mostly Guatemalan migrants were murdered in January with the suspected involvement of state police. But migrant advocates said that is not universally applied, nor is it the case along the entire 3,145-kilometer frontier.

At the border, prices for families desperate to cross have shot up, and some smugglers are offering package deals for a specified number of attempts. Jocsan Avilés, a Honduran, said the going rate in Tijuana was now $7,000.

Even staying put can be costly, with migrants in camps charged 10 pesos (50 cents) to use a local toilet and as much as 80 pesos for a shower — an exorbitant amount for those who have no work and rely on aid from relatives in the U.S.

Mexico was derided as being Trump’s border wall after President López Obrador defused Trump’s threats by mobilizing security forces to deter and expel migrants.

![]()

Toeing the U.S. line on migration still appears advantageous. As Mexico announced this week it was restricting travel on its southern border, Washington acceded to López Obrador’s appeal to share Covid-19 vaccines.

The White House denied there was a quid pro quo, but “I fully expect the Biden administration to lean in on Mexico to step up enforcement as a way to quell rising numbers at the southern border because that’s how this story goes,” Pierce said.

Andrés Rozental, a former deputy foreign minister of Mexico, said the White House remained distrustful of the populist López Obrador and “aren’t sure what he’s really committed to doing — I assume that test will come.”

In the Tijuana camp, rumours were flying that migrants would be evicted on March 21. Biden has also toughened his tone, saying in an interview with ABC on Tuesday: “I can say quite clearly — don’t come.”

For many already on the border, going forward may be impossible but going back is out of the question.

“They’d recruit me into the mara and kill my family,” said Yoima Carías, 13, referring to brutal gangs whose extortion and threats forced them to flee Guatemala City in the middle of the night two years ago.

“We’re not terrorists, we don’t mean any harm,” said Rosy Belloruíz, 35, from the Mexican state of Guerrero. “We just want a better life for our children.”

© 2021 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.