A proposal by President López Obrador that the National Guard be incorporated into the Ministry of National Defense (Sedena) appears doomed after the Labor Party (PT), an ally of the ruling Morena party, indicated that it doesn’t support the plan.

López Obrador said Tuesday that he intends to propose a constitutional amendment in 2023 so that the National Guard, a two-year-old civilian security force, can become a branch of the army.

Such a reform would require two-thirds support of Congress. But Morena and its allies don’t have a two-thirds majority in the Senate and are set to lose their supermajority in the lower house as a result of the June 6 elections, although the president raised the possibility that the government could seek the support of some Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lawmakers.

López Obrador justified his plan by saying that he doesn’t want the National Guard to suffer the same fate as the Federal Police force, which he charged was left to rot after it was established during former president Felipe Calderón’s 2006–2012 government.

“It was spoiled to such an extent that he who was public security minister in the government of Felipe Calderón is in prison,” he said, referring to Genaro García Luna, who was arrested in the United States in 2019 on charges that he colluded with the Sinaloa Cartel in a drug trafficking conspiracy.

“In addition, that police [force] didn’t do its duty and didn’t act with professionalism,” López Obrador said.

The president wanted the National Guard to be part of Sedena and to have a military commander from the beginning but changed tack amid pressure from a range of non-government organizations, which argued that incorporating the new security force into the military would perpetuate the failed militarized public security model introduced by Calderón in 2006.

The National Guard is officially the responsibility of the civilian Public Security Ministry, but during the first five years of its existence, its operation is overseen by the army and navy in order to instill military-style discipline in the new force and ensure that it meets the same standards as those required of the armed forces.

López Obrador said Tuesday that his administration doesn’t want responsibility for the National Guard to be transferred to “the Interior Ministry or another institution” and for it to be “spoiled” six years after it was established.

He added that he doesn’t want to leave office without having proposed “the things I believe the country needs.”

However, getting the Congress to approve a constitutional reform that incorporates the National Guard into the army will require the support not only of lawmakers affiliated with Morena but also many of those from opposition parties, especially if the ruling party’s allies — the Green Party and the PT — don’t vote in favor of the initiative.

PT lawmakers indicated Wednesday that they don’t support the president’s plan, although they reaffirmed their commitment to continue backing López Obrador in a general sense until the final day of his presidency.

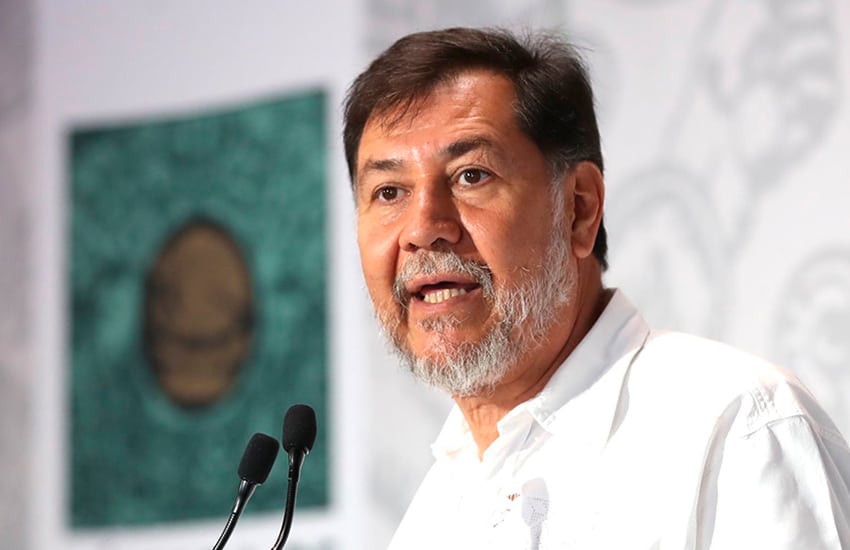

Speaking after a meeting with his fellow deputies, Gerardo Fernández Noroña said the government has a commitment to withdraw the army from the streets in March 2024 and López Obrador’s proposal would contravene that promise.

“We share the concern about [the need] to combat insecurity and to keep the National Guard out of corruption but I believe that there is a way to achieve that without incorporating it in the Ministry of Defense,” he said.

The coalition made up of the National Action Party (PAN), the PRI and the Democratic Revolution Party also rejected the president’s proposal.

PAN Senator Julen Rementería described the plan as “madness,” asserting that the president is attempting to “completely militarize” public security.

López Obrador has also indicated that he intends to propose constitutional amendments to reform the energy sector and to get rid of the election of lawmakers via proportional representation.

The PT said that it would support an energy sector overhaul – the president is aiming to wind back the previous government’s reform that allowed private and foreign companies into the Mexican oil and electricity market – but was not enthusiastic about the latter proposal.

With reports from El Universal and Milenio