Mexico’s efforts to recover thousands of pieces of art and archaeological artifacts from beyond its borders scored another victory this week.

On Wednesday, it was announced that more than 50 items have been repatriated — most notably an urn of Zapotec origin that was made between A.D. 600 and A.D. 900 and a column fragment taken from a palace in the Santa Rosa Xtampak archaeological site in Campeche.

The items in this recent batch were given to Mexico voluntarily by citizens of Austria, Canada, Sweden and the United States. They were handed over to Mexican embassies and consulates abroad as part of #MiPatrimonioNoSeVende (“my heritage is not for sale”) campaign, an effort to recover historical items that were stolen from Mexico or somehow ended up in foreign lands.

So far, nearly 9,000 pieces have been recovered over the past three years, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs — although experts warn that there is a lack of infrastructure to house, restore, preserve and display the items.

The collected works have been taken in by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). In a statement, INAH said the purpose of the campaign is twofold: “the recovery of [Mexico’s] cultural heritage illegally stolen from the country,” and raising awareness that these often valuable items are out there and should not be sold or put up for auction.

“Each object tells us a story that helps us understand our identity as a nation,” INAH said in the statement. The newly returned items are pieces “belonging to different cultures from different periods of the pre-Hispanic era.”

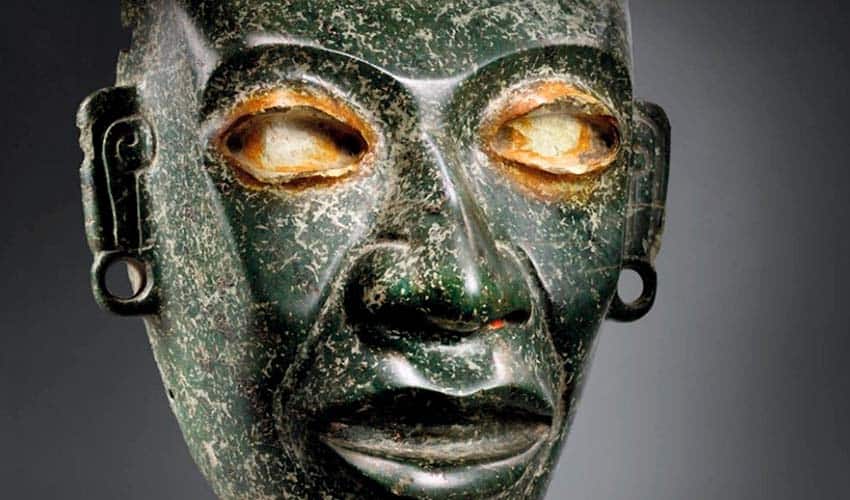

The program has met with success, such as last year when the Mexican Embassy in Germany received 34 pieces such as bowls, pottery vessels and an anthropomorphic mask from the Olmec culture. Also last year, a French family returned four pre-Hispanic artifacts, including a pipe, vessel and figurines that might have been more than 2,000 years old, to the Mexican Embassy in Paris.

However, despite Mexico’s efforts, some of the country’s heritage items have been sold at private auctions.

Last year, for example, an auction at Christie’s in Paris sold some 50 Mexican pieces for US $1.8 million, including a Mayan hacha or ax (a Mayan ballgame accoutrement) that sold for US $839,396. Also last year, a Maya stone effigy sold for US $352,800 in an auction at Sotheby’s in New York that brought US $657,500 for two dozen artifacts from states such as Veracruz, Colima, Jalisco and Zacatecas.

According to Mexico’s Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Culture, the campaign to repatriate artifacts during the administration of President López Obrador has dwarfed the results of the previous administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, which brought back 1,300 pieces between 2012 and 2018. The current government claims 8,970 objects have been recovered in the past three years.

“We must applaud the initiative to recover our archaeological heritage abroad,” said Jesús Sánchez, an INAH archaeologist for 42 years. “However, it’s not just about getting the pieces back. Our work centers have very small warehouses [that are] in poor condition, and the museums are saturated. There are thousands and thousands of archaeological pieces that are stored in warehouses, simply because there is no way to study them, classify them and later display them.”

Indeed, only a fraction of the recovered pieces are on display. Some of the 2,500 objects recovered from Spain are on exhibit in the Templo Mayor Museum in Mexico City, but most others remain in warehouses, perhaps never to be seen by the public.

The legal adviser of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Alejandro Celorio, explained that officials are trying to “stagger” the arrival of objects in the country while they are guarded in embassies or consulates abroad. “There are going to be many pieces and more returns,” Celorio said. “Perhaps we are victims of our own success.”