In the late 1980s, I completed my social service, a standard college requirement for Mexicans, aboard a longline shark-fishing vessel in the Pacific Ocean. I examined the large, freshly-caught sharks as they wriggled and struggled on the vessel’s deck, sometimes slicing them open. As the fishermen reeled in the longlines, so many desperate and dying animals filled the deck that it was difficult to move around safely.

The scene left me pensive. It seemed unfair that a creature that evolved as a top predator hundreds of thousands of years ago would end up being treated like that, only to become a piece of meat. In those years, even less was known about the biology of sharks. It was then that I saw clearly in my mind that my destiny was to become a shark researcher.

Sharks are a strange kind of fish: normally, fish lay eggs and warm-blooded mammals (like humans) have live babies with an umbilical cord. But sharks have been swimming the world’s oceans for so long that some shark species have independently evolved the ability to give birth to live babies, giving their young a greater chance at survival. They are also incredibly ancient creatures that evolved over 400 million years ago, long before the first dinosaur was born.

Shark fishing in Mexico dates back to the time of the Olmecs and the Aztecs. It started as a small-scale subsistence activity for coastal communities. At first, it was just an artisanal (small-scale) industry. Fishermen used small boats (canoes and pangas) to capture coastal sharks with harpoons, hooks, and later nets. The fishery spread throughout the country’s coastal areas, and became more commercial, using large vessels with greater autonomy and storage capacity.

According to the CONAPESCA Fisheries Statistical Yearbook, in terms of catch the shark fishery in Mexico is one of the most important worldwide. Historically, catches are reported into two categories: tiburón for adults from large species (more than 1.5 meters) and cazón for young sharks from large species and adults from small species.

In Mexico, shark meat has long been a low-cost protein as well as a source of employment and income. The meat is eaten fresh, dry-salted, or smoked, and it is the base of many typical regional dishes, such as pan de cazón, a traditional dish in Campeche and Yucatán.

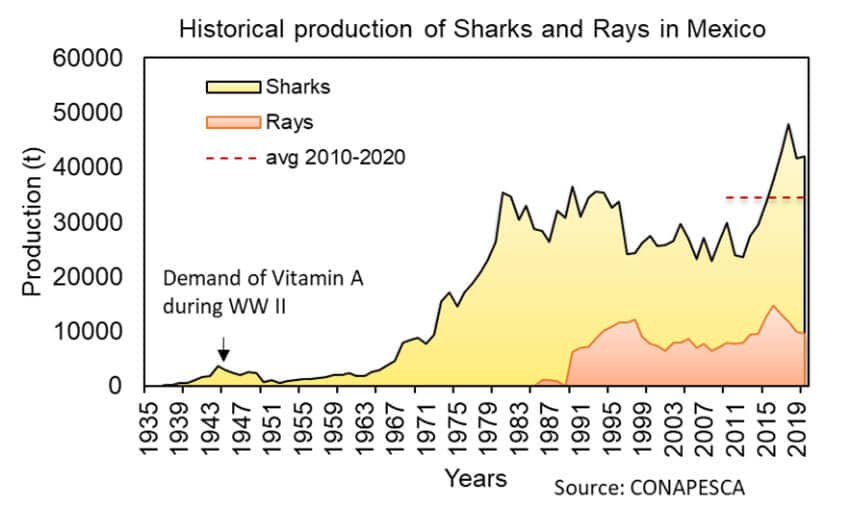

Other shark byproducts have their uses as well. There is demand for the skin, cartilage, fins in the Asian market and shark liver oil can be a source of vitamin A, a use which was common during World War II. Demand from the shark leather and shark liver oil industries was reflected in the first uptick in national shark catches in the 1940s. At that time, no one knew that Mexico would become one of the top ten nations in the world in shark production, catching an average 35,000 tonnes per year over the last decade.

Rays, which are closely related to sharks, are also targets of fishing. Both species belong to a group of fish called chondrichthyans, which have a skeleton made of cartilage rather than bone. Both sharks and rays also share traits that make them vulnerable to fishing. They grow slowly, are generally long-lived and take many years to become sexually mature. When females finally reach maturity, they produce just a few young after a prolonged gestation period — longer than 12 months in some species. These life history traits mean that shark and ray populations grow very slowly compared to species like sardine and shrimp.

The artisanal ray fishery, which dates back to at least 1986, is small-scale and coastal, and provides food and employment to workers, just like the shark fishery. The industry caught 14,700 tonnes of rays in 2016. Both fisheries have been able to develop thanks to factors including the privileged geographical position of our country, favorable ocean dynamics and high diversity of species.

Over time, the industry has changed. Some species that were once common haven’t been seen for years. Fishermen are still bringing home the same quantity of shark meat, possibly because Mexico has a diverse shark population with a huge number of species. Though the yearly catch remains high, the size of the populations is still unknown, and in some cases the outlook is not very encouraging.

One of the most worrying trends is the frequent capture of young or pregnant sharks. Tropical species of sharks (and some rays) use shallow water areas such as bays, estuaries, and beaches for the birth of their young. These “nursery areas” provide food and protection for newborns during their early development. However, because Mexican artisanal fisheries occur in coastal areas, the nurseries and fishing zones overlap. As a result, pregnant females and juveniles often get caught in nets and by hooks, with potentially devastating effects for shark and ray populations.

In the entire world, there are 536 species of sharks and 670 species of rays. In Mexico, 200 species of sharks and rays have been recorded, a large proportion for just one country. In the Pacific Ocean, 63 species of sharks and 55 rays have been documented. In the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, 75 sharks and 47 species of rays have been recorded.

There is now more shark fishery regulation than in the past, but lack of inspection and enforcement reduces the laws’ efficacy. Illegal fishing continues and sharks can become bycatch in other fisheries. In addition, the management of shark fisheries with deep-rooted socioeconomic relevance is complex, and reconciling social, economic, and ecological interests is challenging.

Shark fishing is an important source of employment and income for some coastal communities, but the frequent capture of juveniles and pregnant females puts shark populations at risk. The solution to this dilemma is not easy and requires dialogue between the fishing sector and decision-makers. At the same time, collecting information on the species’ basic biology will help guide those decisions. Sharks became top predators through millions of years of evolutionary adaptations but those same life history traits are a disadvantage in the face of the extreme exploitation of shark populations around the world.

Increasing awareness among authorities, fishing communities and shark meat consumers is a step toward making better decisions about shark research and fishery monitoring.

Fernando Márquez-Farías is a professor of fishery biology in the Ocean Sciences Department (Facimar) of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa.