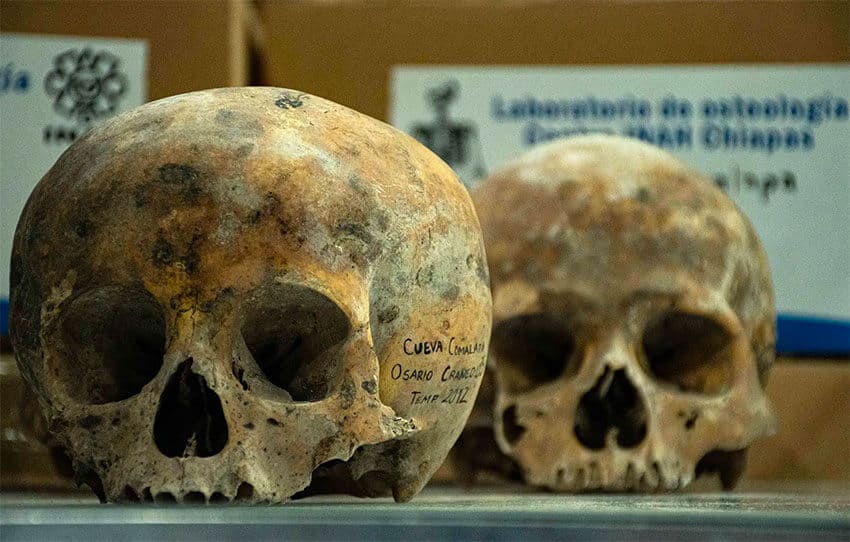

Some of the 150 skulls found in a Chiapas cave 10 years ago had been deformed to look like jaguar heads, according to a National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) researcher.

INAH announced earlier this year that the skulls found in a cave in a municipality on the border with Guatemala in 2012 are not the craniums of recent victims of violent crime as investigators originally thought but belonged to Mayan people who were likely killed in a sacrificial ritual between A.D. 900 and 1200.

Javier Montes de Paz, a researcher with INAH, told the newspaper Reforma that the skulls belonged to women, children and men who were captured and decapitated by a rival group. Teeth were removed from the skulls, which were placed on a skull rack called a tzompantli, according to INAH, which has studied the craniums over the past decade and determined they are approximately 1,000 years old.

“It was an altar — not to venerate so much as to show to the opposing people,” Montes de Paz said.

He said that some of the skulls showed signs of “intentional cranial deformation,” but they weren’t deformed by the captors. Rather, the skulls of people destined to become warriors were modified from birth to resemble jaguar heads, Montes de Paz said. The plasticity of young skulls allowed them to be modified, he said, adding that the purpose of the distortion was to make them look ferocious. In addition, the jaguar is revered by Mayan people, and there are numerous jaguar deities.

“They deformed the head because they wanted to look like [jaguars],” Montes de Paz said. The desire for would-be warriors to resemble the feline was so great that they didn’t just modify the shape of their heads but also performed “surgery to cause a squint because the jaguar has stereoscopic vision,” he said.

“The deformation mainly occurred among warrior groups or those who were destined to be military chiefs, because they had to instill fear in the enemy,” the researcher added. To achieve the desired cranial alteration, he explained, a couple of thin wooden boards or ceramic slabs were attached to a person’s head to place pressure on certain parts of the skull. The sought-after effect could take up to five years to achieve, Montes de Paz said.

The researcher said that warriors or would-be warriors who were captured were stripped of the ferocity their deformed skulls afforded them via decapitation and the removal of their teeth, which were also altered to resemble those of jaguars. He said it hasn’t yet been determined whether the teeth were removed before or after the victims were sacrificed. Montes de Paz predicted that further study of the skulls will allow researchers to understand even more about the people they belonged to and those who captured and killed them.

The researcher noted in a previous interview that 124 toothless skulls were found in the 1980s in a cave in the Chiapas municipality of La Trinitaria, which is also on the border with Guatemala. Five other skulls that were also probably part of a tzompantli were found in 1993 in a cave in Ocozocoautla, a municipality in Chiapas’ northwest.

With reports from Reforma