Representatives of civil society organizations have denounced a proposed tax reform that was approved in general terms by the lower house of Congress on Monday, warning that they will receive fewer donations if it becomes law.

The ruling Morena party is seeking to reduce the percentage of income a worker can claim in deductions.

An individual can currently claim deductions for an amount equivalent to up to 32% of their income but if the proposed reform passes Congress the figure will decline to just 15% in January. The 32% figure includes claimable deductions of up to 15% of one’s income for expenses such as medical, education and transport costs, 10% for retirement fund contributions and 7% for donations made to civil society organizations.

But under the proposed reform – whose objective is to collect more tax revenue to increase funding for government social programs – there will be no specific quota for tax-deductible donations. Instead, the makeup of the 15% maximum deduction will be at the discretion of the individual taxpayer.

Representatives of several organizations say the proposed reform will take away the incentive for citizens to make donations.

“People don’t donate to deduct taxes … but rather out of conviction, [because they want] to support causes and help the neediest people. But the act of removing these kinds of tax incentives doesn’t contribute to the strengthening of a philanthropic culture that is sorely needed in Mexico, especially in a context of pandemic, violence and economic crisis,” Dominique Amezcua of the organization Alternativas y Capacidades told the news website Animal Político.

Abril Rocabert of the same organization – which aims to strengthen the “ecosystem” in which Mexican civil society organizations operate – said the removal of the tax incentive for donations would affect more than 5,000 civil society organizations.

“In many cases donations allow civil society organizations to pay for their entire operations so losing them or seeing them seriously reduced could compromise thousands of social assistance services,” she said, noting that more than 700,000 people are employed by such organizations.

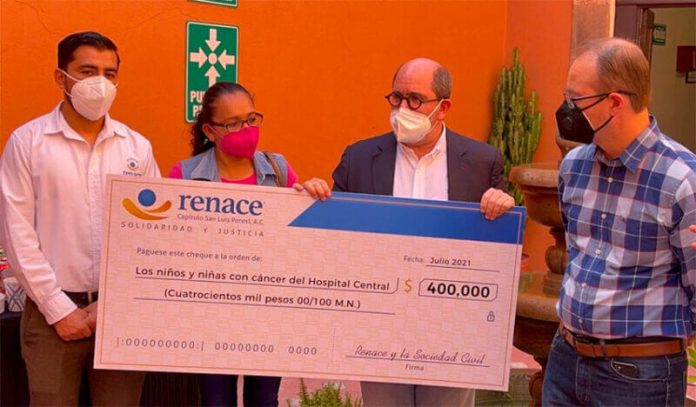

Among the groups that would be affected are those that support cancer victims, assist migrants, provide free legal help to low-income people, run shelters for victims of domestic violence, defend human rights and protect the environment.

The director of the Network for Children’s Rights in Mexico told the newspaper Reforma that the tax bill is a “disproportionate measure.”

Tania Ramírez said the extra revenue the government would take in as a result of the reform would not be significant in terms of overall tax collection. However, the amount of money civil society organizations receive in donations – some 8 billion pesos (US $395.1 million) annually – is very significant for them, she said.

Ramírez said it was regrettable that the parliamentary majority led by Morena has not listened to the concerns of civil society.

Edith Olivares, executive secretary of Amnesty International in Mexico, said the survival of thousands of organizations will be threatened if the proposal passes Congress.

“Many civil society organizations live off small donations from private citizens,” she said, adding that the money, in Amnesty International’s case, is used to denounce human rights violations.

“We think that a measure of this kind adds to the constant federal government narrative of insulting the work of civil society organizations; we can’t see it outside this context and that’s why we’re so worried,” Olivares said.

President López Obrador has railed against civil society organizations he sees as opponents of his government, such as Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity and press-freedom group Article 19, and even sent a diplomatic note to the United States government asking it to explain why it funds such groups.

José Mario de la Garza, a lawyer and president of an organization that provides free legal advice to low-income people, said that “reading between the lines” one could reach the conclusion that the federal government’s objective with the tax reform is to weaken civil society organizations, especially the ones that are most critical of the government.

“… [The text] of the proposed reform doesn’t say it but in practice it would seem that the interest of the government is to limit the resources organizations receive so that their participation [in Mexican society] is greatly reduced and counterbalances are avoided,” he said.

“In other words what this reform is seeking to do is to weaken the system of checks and balances on government by limiting the funding possibilities of civil society organizations that depend on donations.”

David Pérez Rulfo of the Jalisco-based community organization Corporativa de Fundaciones noted that only 35% of donated amounts are tax-deductible and therefore less than 3 billion pesos out of the approximately 8 billion pesos donated annually can be deducted from people’s tax obligations.

The amount tax authorities are currently missing out on due to tax deductions is minimal when compared to the size of the federal budget, he said.

If, as expected, the reform passes both houses of Congress and becomes law, Mexico runs the risk of being left without a range of services that vulnerable people depend on, according to Ricardo Bucio, president of the Mexican Center for Philanthropy.

“The government is seeking to attend to needy people with its [social] programs and that’s good,” he said.

“But civil society organizations provide services to needy and vulnerably people that the state – the three levels of government in other words – doesn’t have the capacity to look after. For example, a child with a disability is not taken care of with a bimonthly scholarship of 2,700 pesos [US $133] nor do you improve the life of a female victim of violence with a monetary transfer,” Bucio said.

“That’s why the permanent presence [of civil society organizations] is needed, … their participation [in society] is essential,” he said.

With reports from Reforma and Animal Político