I just finished reading last week’s CEO perspective, where Travis shares his outlook on

the return of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans to their homeland due to mass deportations and voluntary decisions by Mexican citizens to return to Mexico. Yet, as

I read, my thoughts wandered to challenges that lie beneath the surface of such

optimism.

Travis underscores the importance of closer collaboration between the private sector

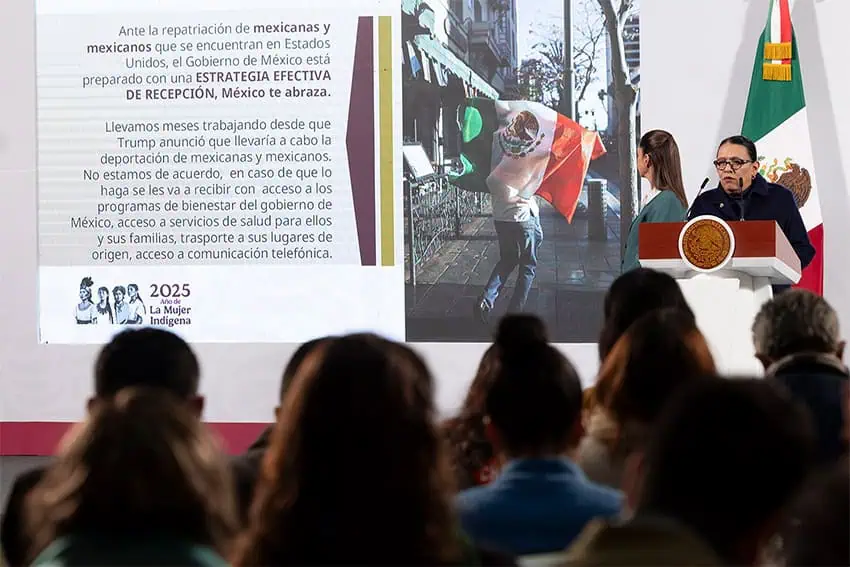

and government to create opportunities. However, a closer look at the government’s “México te abraza” (Mexico Embraces You) program tells a different story.

Jobs for the repatriated

This initiative aims to assist repatriates with reintegrating into Mexican society. Among its strategies is helping returning migrants find employment.

Upon arrival in Mexico, migrants are quickly approached at immigration offices by

officials from the Interior Ministry and the Labor and Social Welfare Ministry. They are informed about the program, advised on how to re-enter the workforce in Mexico that aligns with their previous skills — be it construction, services, manufacturing or technology — and guided through procedures to register with the SAT, Mexico’s tax collection agency, and IMSS, Mexico’s social security agency. Some companies even assist with opening bank accounts or updating legal status in Mexico.

According to the latest data available from the Interior Ministry, as of September, a total of 112,260 repatriated Mexican citizens had arrived from the United States across Mexico in 2025. The largest number of them, about 33,000, ended up in one of three Tamaulipas cities: Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa-Hidalgo and Matamoros. The other states that received the most repatriated citizens have included Sonora (15,734), Baja California (14,594), Chihuahua (13,808) and Tabasco (12,043).

In a year marked by declining employment prospects in Mexico, data from a report by Mexico’s Business Coordinating Council indicates that a coalition of 381 member companies in Mexico, in coordination with the federal government, had so far generated 70,500 job vacancies for the repatriated. These include major corporations in Mexico such as FEMSA, Bimbo, PepsiCo, CEMEX, Walmart, Lala, Bayer, Grupo Carso, Xignux and Grupo Posadas. Clearly, these efforts embody a partnership between private enterprise and government, as Travis noted, that Mexico needs more of.

However, a closer look at this good news shows that these new jobs are mainly concentrated in the following states:

- Nuevo León (10,092 jobs)

- Mexico City (8,147)

- Jalisco (5,418)

- México state (5,105)

- Baja California (3,386)

- Guanajuato (3,323)

- Querétaro (3,138)

- Coahuila (3,122)

- San Luis Potosí (2,515)

- Puebla (2,323)

In each of the rest of Mexico’s 32 federal entities, 2,000 or fewer jobs have been so far created under this initiative.

When you start to compare where Mexico says the repatriated ended up, one sees an unfortunate mismatch: While the highest level of job creation under this initiative was in the northern state of Nuevo León, that state wasn’t even on the list of states where the repatriated were received in 2025. A mere 1,187 jobs were created in Tamaulipas, the state in which the most repatriated persons — over 30,000 — arrived.

Salaries for these jobs range from as low as US $450 to as high as US $5,000 per month — roughly US $5,400 to US $60,000 annually. “México te abraza” also offers a small initial stipend of about US $110 intended to cover transportation costs back to the returnees

community of origin.

These facts begin to address a deeper question: Why do so many of these repatriados appear absent from Mexico’s labor market? While these job and immigration numbers provide some insight, the answer isn’t simple, it’s one woven from data, cultural bonds and perhaps something else more profound.

According to a study conducted in 2021 for the United Nations through the International Organization for Migration, 64% of Mexican migration to the U.S. is driven by the pursuit of a higher family income. The second most common motivation is fleeing insecurity and violence in cartel-controlled regions, which push people to seek safety elsewhere. The third is the desire to reunite with families already established in the U.S.

If economic factors are the main driver, the numbers reveal a stark reality. According to recent data from INEGI’s National Employment and Income Surveys, wages in Mexico fluctuate between roughly $500 and $3,000 per month, depending on the region, sector and education level.

This range of income, even considering recent increases in the minimum wage, illustrates a persistent gap: Mexico’s wages still lag significantly behind those in the United States.

|

Category |

Mexico (2025 estimate) |

U.S. (2025 estimate) |

How much does the U.S. pay more? |

|

Unskilled / Agricultural / Service Jobs |

~$235 – $315 USD |

$2,200 – $3,200 USD |

About 7-14 times more |

|

Skilled / Specialized Jobs |

$631 – $1,052 USD |

$3,500 – $6,000+ USD |

About 4-10 times more |

*Adjusted for currency exchange rates ($1 USD = $19 MXN). Data sourced from INEGI and the Immigrant Research Initiative.

And if these returnees didn’t migrate primarily for economic reasons, security might have been their main concern.

The majority of those returning come from states like México state, Jalisco, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Puebla, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Chihuahua and Mexico City. With the exception of Oaxaca, all of these states rank high on insecurity, meaning many are likely returning to towns where they once felt unsafe. In some cases, they might have faced threats or violence that compelled them to flee — making the idea of returning to their hometowns seem perilous rather than promising.

A personal view

Guanajuato and Michoacán — places where I spent summers as a child — have long

been marked by social and economic shifts driven by migration, remittances and,

increasingly, cartel activity. Take, for example, Andocutín, a small Guanajuato town just five minutes from the state of Michoacán where my grandparents’ ranch is located.

With fewer than 200 homes and fewer than 800 inhabitants in this village, finding a decent-paying job is nearly impossible. About 80% of the population is made up of the elderly, young women and kids; their incomes are the remittances that their fathers, husbands, sons or grandsons send them. Nearby towns like Irámuco and Zinapécuro, though more prosperous, are also shadowed by extortion, violence, and the influence of narcotraffic—factors that have shattered local economies and social cohesion.

Returning to communities like Andocutín isn’t really an option, and so most returnees would need to migrate elsewhere — probably to larger cities, where there are more work opportunities and safer environments. And if everything these immigrants had was left behind in the hometowns they fled, would they really want to go back there to start from scratch?

Imagining myself in their situation, I would prefer to fight to return to the place where I had migrated, back to where I had worked hard to construct an entire life — rather than going back “home” and return to a cycle of uncertainty in Mexico.

I agree with Travis that emotional ties heavily influence these decisions—what he refers

to as the “disappearance” of repatriates from the labor market isn’t just about skills or

opportunity but also about profound personal and cultural connections. This emotional

burden might explain why so many seem “absent” from available jobs — perhaps they’re

simply not present in a straightforward sense, at least not immediately or easily.

How returnees can help Mexico

Trump’s immigration crackdown could have a silver lining for Mexico: A perspective from our CEO

And like Travis, I see a silver lining if some of these returnees choose to stay and engage

with their communities. Their bicultural experience, bilingual abilities and understanding

of both U.S. and Mexican societies could serve as powerful catalysts for change. If I

were in a position of influence — either in a company or in government — I would view

these returnees not just as labor but as cultural bridges, guides capable of reshaping

Mexico’s social and economic landscape.

First, I would seek to interview them, listen to their stories and understand their

perspectives. Their unique dual cultural identity is a tremendous asset — one

that, from another vantage point, is a strength rather than a weakness. Their experience navigating two worlds can be a catalyst for innovation and cultural exchange, especially in industries like tourism, where the understanding of foreigners and their culture is paramount.

Second, many of these returnees could be invaluable as advisors within immigration

and employment programs. Their personal stories, adaptability and language skills

position them perfectly to help design policies that are compassionate, culturally

sensitive and more effective. Engaging them in this way could transform programs from

mere bureaucratic procedures into opportunities for genuine inclusion and growth.

Most importantly, they hold the potential to become agents of a new kind of

resilience — if they are embraced and guided properly. Mexicans are renowned for their

hospitality, resilience and ability to turn hardship into strength. The unique perspective

of returnees — those who straddle both worlds — could be integral to building a more

inclusive, dynamic Mexico.

Ultimately, their stories transcend jobs; their stories are about identity, belonging and the hope of building a better future rooted in the roots they carry back. If Mexico can harness this potential, it might find its own version of a silver lining — one that stems from the

strength, ingenuity, and resilience of its people.

Travis concludes his article by suggesting that this situation presents an opportunity for

Mexican-Americans to reconnect with their heritage. For me, the real challenge isn’t just making them feel welcome but making Mexico appealing enough for them to choose to

stay — especially in the communities their parents and grandparents came from.

How can we revive the vibrancy of places like Andocutín? European governments, for example, use targeted incentives to revitalize small towns — boosting local agriculture, investing in education, and fostering safe, strong communities. I long to see similar efforts to revive the economic activity once fueled by my grandparents’ ranch. But to do that, I would need the certainty that my family, land, and community would be safe. Without that security, even the strongest ties to home risk being uprooted again, leaving a cycle of hope and abandonment in its wake.

If Mexico can create environments where returnees feel valued, well-paid, protected and truly at home, perhaps we can transform these stories of departure and return into stories of renewal, resilience and lasting connection.

Maria Meléndez is an influencer with half a degree in journalism