In 2015, Germany returned two 3,000-year-old Olmec wooden statues to Mexico. They had been seized from a dubious Costa Rican art collector and kept in the Bavarian State Archaeological Museum until the courts could settle the issue of ownership. Their return was described as “an important precedent in favor of Mexico.” In fact, getting its artifacts back has been a Mexican concern for several years now.

The issue of returning archaeological items to their original country is very much in the spotlight, most famously with the ongoing demand for the Parthenon Marbles to be returned to Greece. Mexican items, however, do not tend to attract quite the same headlines.

Compared, for example, with ancient Egypt, there are relatively few Mexican items in European and American museums, and although many of these are of considerable interest, they tend to be smaller items — and undramatic compared to the Rosetta Stone or the Beard Of The Sphinx.

Returning items to their nation of origin is not always a clear-cut issue. Few would argue, for example, against returning items stolen from the Baghdad Museum in the recent post-invasion chaos of the U.S. takeover of Iraq, but older items, acquired legally — if perhaps immorally — become a gray area.

Many items in the world’s big museums are there as a result of a formal sharing agreement between a university — who took on the cost of a dig — and the home nation (although this is not always the case). This links with the idea of “cultural internationalism,” which argues that cultural property is not tethered to one nation but belongs to everybody.

There are certain advantages to spreading human art around the world. How many tourists, pouring money into the Egyptian economy, have been inspired by a visit to the British Museum? Having objects in foreign museums also gives some protection from wars and natural disasters.

What would you say are the highlights of Mexico’s rich precolonial past now sitting in world museums? This is a very personal choice, and I’d love to hear your input. As a historian, librarian and archivist myself, here are what I consider my five highlights:

5. Human and animal figurines: the Arizona Museum

The Arizona Museum is billed as a natural history museum, and dinosaurs are indeed the main attraction. However, the curators are aware that their town — located just 300 kilometers from the Mexico-U.S. border — shares much of its culture with northern Mexico, and so the entrance to the Mesoamerica and South America Gallery is dramatic: a giant replica of an Olmec head.

The museum’s collection is largely from Jalisco, Nayarit and Colima, where there was, as the museum describes, “a culture contemporary with, but isolated from, the better known Mexican civilizations.”

This region of Mexico was noted for its figurine artifacts of humans and animals, largely collected from shaft tomb burials. Dogs were a favourite subject of these ancient ceramic artists since the animals were believed to be guides to heaven and protectors of ancestors. I love the one titled “Dog with Red-Orange Burnished Slip,” a particularly fine example of the type, featuring a nice touch of humor as the dog scratches its ear, presumably to get rid of annoying fleas.

4. Olmec objects: NYC’s Met Museum

The Met houses one of the most impressive archaeological collections in the world, and is particularly rich in Egyptian, Greek and Assyrian artifacts. The collection of Mexican items is smaller, but it does contain some gems, with the “Seated hollow figure with helmet” being a personal favorite. It dates from between 1200–800 B.C., which makes it at least 2,000 years older than the Mexica civilization.

The statue shows a well-fed child, with folds of fat, gazing upwards, hand to its mouth. Several of these pudgy Olmec babies have been found, with one theory about them being that they were created to advertise how wealthy the society was. Although the origins of the “Seated Hollow Figure with Helmet” are uncertain, it is thought to come from the central highland site of Las Bocas, in the state of Puebla, a region where a number of Olmec-style ceramic objects have been unearthed.

3. Mexican collection: Berlin Ethnological Museum

This museum houses 500,000 works of art and culture from outside Europe, making it one of the largest and most important such collections in the world. The Mexican collection was started in the middle of the 19th century by Ferdinand Conrad Seiffart, the Prussian General Consul in Mexico, and was continued by the merchant Carl Uhde and the scholar Eduard Seler.

Due to these varied sources — and poor record-keeping in the museum’s early days — there is no precise information on where many of the objects were found. The item I have focused on, “A Clay Figure with Movable Limbs,” is perhaps the finest of a series of clay figures where the limbs are attached to the body with threads. Whether they were dolls, puppets, a child’s toy or created for a magical role is a subject of academic debate. Indeed, it is what we don’t know about this wonderful piece that makes it so exciting.

2. Borbonicus Codex: Paris National Assembly

One of the greatest crimes humans have ever committed against another culture is Spain’s destruction of Aztec art. Particularly targeted were the Aztec codices, stories recorded onto long sheets of fig-bark paper — known in Mexico as amatl — and primarily pictorial in nature. As a result of the conquistadors’ efficiency, only three codices dating to the precolonial period are believed to have survived. One of these is the Codex Borbonicus. It resides not in Mexico but in France.

This is a single sheet of bark paper, 14.2 meters long and generally accepted to have been created by Mexica priests shortly before, or possibly just after, the Spanish conquest of their civilization. The story of its survival is uncertain, but at some point, the codex was brought to Spain and then ended up in France in 1826, when it was acquired at auction and given a home in the library of the National Assembly in Paris.

The Codex Borbonicus describes Mexica divinatory and solar calendars through a range of colorful scenes that include animals, people and deities. It also contains annotations in Spanish, which is one reason the precolonial date is disputed. There are many who believe, however, that these were added sometime after its creation.

This is one Mesoamerican item that’s the subject of an ownership dispute: In late 2024, representatives of the Hñahñu — known more widely as the Otomi — wrote to French parliament ministers, asking them to support their call for the codex to be returned to its homeland. Some parliament members have promised to put the Hñahñu’s request as a written question before the legislative body, according to the French newspaper Le Monde.

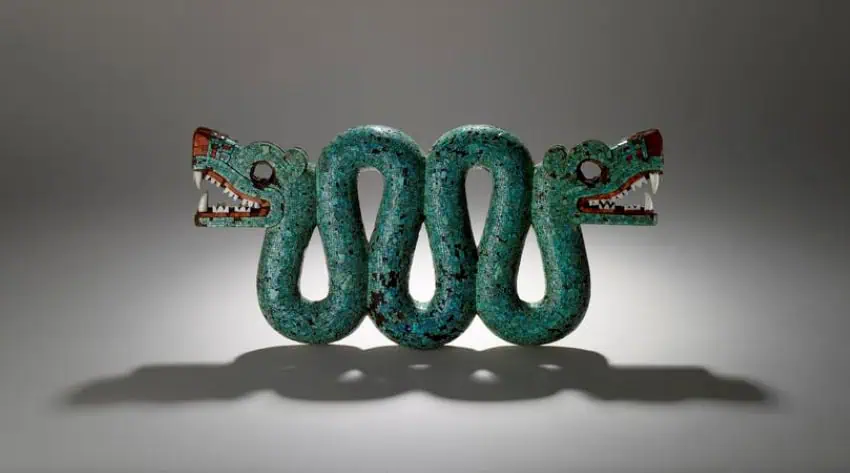

1. The double-headed serpent: The British Museum

There was little problem in selecting the item to take the top spot, a doubled-headed serpent kept in the British Museum. Made of cedro wood, it’s covered with over 2,000 pieces of turquoise mosaic. White and red oyster shell colors the serpent’s teeth and mouth. It is one of the finest gems of precolonial art anywhere. While there is a generally accepted history of the object, this history contains a fair amount of guesswork.

The serpent was probably made by the Mixtecs and offered to the Mexica as tribute. The journey from Mexico is undocumented, but it might have been among the gifts offered to conquistador Hernán Cortés.

Many such mosaics ended up in Florence workshops, where they were broken up so that the turquoise could be reused to make more contemporary objects. Somebody recognized the importance of the double-headed serpent, and it was spared, eventually finding its way to the English banker Henry Christy, a major collector who left numerous items to the British Museum.

There are only 25 Mexican turquoise mosaics in Europe — nine of which are in the British Museum — and the double-headed serpent is most beautiful and the most mysterious of them all.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.