“My day begins with the night,” Fabiola — a weather-beaten veteran researcher of sea turtle nesting sites — tells me before we depart on her ATV to patrol the beaches of El Cuyo, Yucatán. El Cuyo: where endangered green and hawksbill sea turtles have come to lay their eggs year after year since the dawn of time.

We putt-putt over two kilometers down the beach on a night with no stars, moon, breeze or people. It smells of the sea, and the only sound to be heard (other than our ATV) is the echo of the Caribbean waves on a humid June night. We move forward until the high tide stops us and, to my joy, we are forced to leave to its dark fate the horrendous, noisy, four-wheeled vehicle that doesn’t permit one to contemplate the night or listen to the sea in peace.

I told myself that I would rather walk the full five kilometers that night, patrolling the beach and feeling the wet sand under my feet. These are the times when I need to feel the Earth directly, without intermediaries. I’m now convinced that the only valid reason ATVs exist is to help biologists look for sea turtle nests, and for that reason only, we humans must put up with those dreadful machines.

Fabiola carries in her backpack a small GPS device, a notebook and a few test tubes in which she will preserve samples from the turtles’ skin — upon which genetic studies will be performed. She also carries measuring tape, tags for turtle fins, alcohol to sterilize and who knows what other trinkets. Both of us have red-light lamps on our forehead that, she told me, don’t bother the turtles.

Then, there is me, Fabiola’s accidental field assistant, the one who on his back carries 37 of the thousands of bamboo stakes that she has patiently painted bright red; tonight, she has chosen stakes that number 583 to 620. We will bury them in the sand to mark the turtle nests we find.

Fabiola recycles those stakes from the leftover wood of the jimba de caña brava, one of Mexico’s five native species of bamboo, the same bamboo that fishermen use to catch octopuses along the coast of the states of Campeche and Yucatán. The jimba technique is a diurnal, drifting artisanal fishing method that, I’m told, is environmentally sustainable but is disappearing because the new generation of fishermen don’t want to use it anymore.

I had heard of this bamboo fishing gear’s existence for the first time just the day before while chatting on the beach with Tatiana and Gerardo, two cheerful young fishermen in love who came to El Cuyo from the states of Chiapas and Tabasco years ago. I listened to them while Tatiana’s dad was fishing on a small skiff, accompanied by his old mixed-breed dog, in a nearby area where pelicans and herons feasted on fish and frigate birds soared in slow motion.

At a distance, gluttonous pink flamingos filtered lagoon water with their bills, removing the brine shrimp, Artemia salina, those 15-millimeter-long crustaceans equipped with three eyes and 11 pairs of legs to live in hypersaline water.

These shrimp are stuffed with carotenoids, the pigment responsible for the pink feathers of the flamingos. Brine shrimps are primitive invertebrates that, like us vertebrates, contain hemoglobin in their blood, but they’ve hardly changed over 100 million years of existence — just like sea turtles.

I frequently dreamed of seeing sea turtles laying their eggs on a starry night. Maybe that is because the first time I ever saw Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night I was deeply touched by the subtle dark night colors of browns, grays and pale blues in that sublime painting. Vincent was, of course, hallucinating (for himself and for us) at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

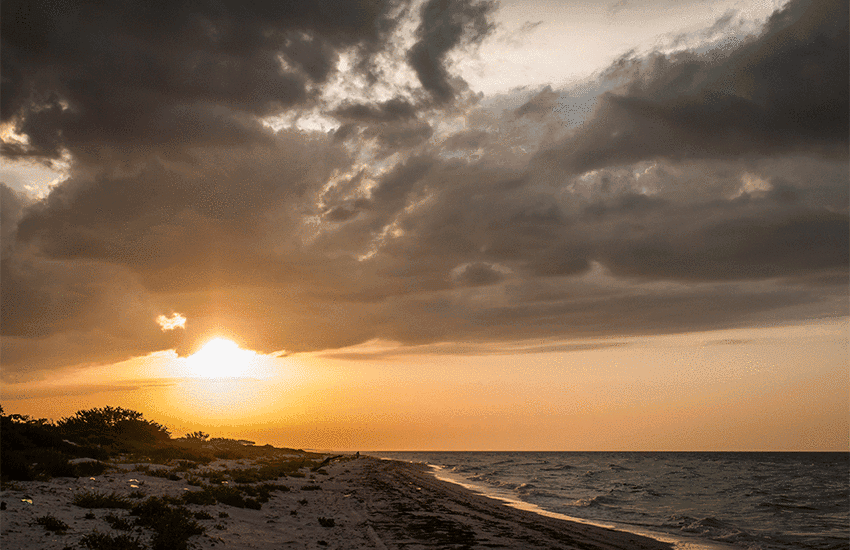

Sadly, my second night in El Cuyo was another non-starry night, a night when, after wandering across several kilometers of beaches, my voiceless frustration had built after seeing, once and again, only the tracks that the turtles left on the sand. No live turtles; only the traces of their zigzagging forward and backward movements from the sea and toward the sea, as if they were undecided where to make their nests.

But just hours ago, Dr. Melania López, an experienced Mexican scientist who leads the sea turtle program of Pronatura Península Yucatán — one of Mexico’s leading non-governmental environmental organizations — told me that El Cuyo is one of the two most important nesting beaches for green and hawksbill sea turtles in the entire Mexican Caribbean, the other one being Holbox Island in the state of Quintana Roo. So I continue walking, looking down in hopes of finding one of those turtles.

I ask myself: maybe they are not coming today, or it just isn’t the right time? Or perhaps they sense our presence and choose to nest elsewhere? Or, even worse, the monstrous and noisy ATV that we abandoned has frightened them away?

Suddenly, noiselessly, in the starless dark where the waves break on the beach, a ghostly turtle-like silhouette unveils itself. Crouching on the sand, just a few meters from the sea, my mouth opens in wonder and I stare at a moving sketch of a sea turtle emerging from the water slowly, almost as if in pain.

Magnificent Chelonia drags herself onto the beach with an unbreakable millenary evolutionary resolve to reproduce. It is a female green sea turtle that relentlessly swam who knows how many thousands of miles or from which far ocean, but she came to El Cuyo, probably the same beach where she was born decades before.

I stop breathing, motionless, sharpening my sight, hearing and sense of smell in the darkness and in the monotonous wash of the waves, trying to discern how this immense ancient marine reptile crawls slowly but meticulously up onto the beach. Unexpectedly, a flip-flop sound gets my attention and makes me look in the other direction.

Then I realize — first thinking for a moment that I’m hallucinating — that another turtle is crawling up the beach, its fins making the sound as it pads its way up the wet sand. I’m in the middle of the track that those two sea turtles must follow to reach the highest part of the beach and dig their nests.

And I have no idea what to do. I’m no more than 10 meters from the two giant turtles. What to do to avoid being bulldozed by them?

The only thing I can come up with is to try and hide motionlessly on the sand as I was instructed to do when in danger as a Boy Scout: hide and allow your eyes to stealthily scan the area.

As if she were smelling my terror (sea turtles have bad sight but a very good sense of smell), the turtle on my right turned to begin moving directly toward me. Instinctively, I turned my head down, placing it against the sand, signaling submission, gazing at that huge armored reptile, begging her not to crush my fragile human kindness.

In retrospect, I honestly don’t know why I behaved like that; it now seems an embarrassing reaction for a field biologist who has spent most of his life roaming the wilderness with wildlife.

I will never know if the turtle recognized my submissiveness ritual, but she stared at me with her big eyes, and when she was barely two meters from my head, she decided to change course and continue on her own path.

Surely, she had more important things to do than going after a frightened human — make her nest, lay her 100-or-so eggs, cover the nest with sand and return to the sea for what Dr. López calls the “lost years” of sea turtles. This is because sea turtles spend only 1% of their lives on land and the remaining 99% on the sea.

Once I recovered from my crushed pride, I joined Fabiola to study the other turtle. I saw how she dug and shaped her nest using her backward fins, a perfect nest as only chelonians know how to create.

I witnessed her slowly lay her eggs as she rolled back her eyes and entered a kind of trance. She then returned to the sea after carefully burying her eggs in the sand. She left with the same determination with which she arrived because she came to El Cuyo with a singular purpose.

And I don’t know why, but this big, slow-moving, single-minded female green turtle left me with a strange emptiness as I have never felt before.

I raised my eyes. The sky was still moonless, but the night was no longer dark. I gazed at shooting stars twinkling against a setting of palm trees that lull themselves to sleep with the breezes, and I had just one wish: to be able to see, one more time, a sea turtle laying her eggs.

But, to my surprise and amusement, those shooting stars proved not to be meteors but the sparkling of dancing fireflies over El Cuyo, that magic place in Yucatán where the days begin at night.

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.