Two lesser-known criminal groups have grabbed headlines in recent weeks for their suspected role in the brazen ambush and murder of women and children in northern Mexico, but how did these so-called “small armies” emerge in the first place?

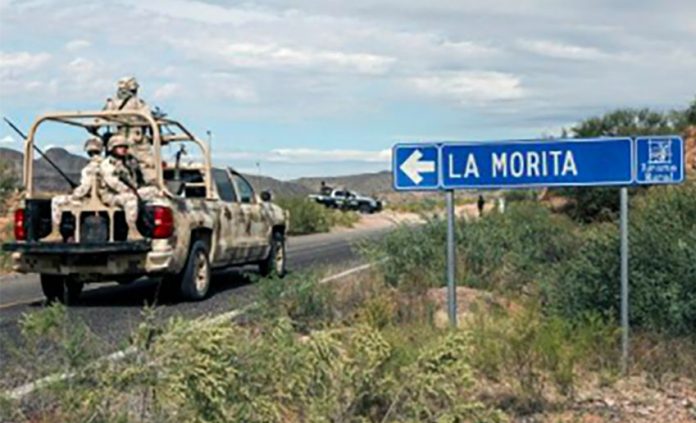

The group of 17 family members from a prominent American Mormon family were traveling in three vehicles when armed gunmen opened fire on the convoy. Nine U.S. citizens — three women and six children — were killed in the onslaught near the small town of Bavispe in northwest Sonora state along the U.S.-Mexico border.

At the center of what led to the attack weren’t Mexico’s traditional cartel powerhouses, but rather two smaller criminal groups: one known as Los Salazar that is linked to the Sinaloa Cartel and operates in Sonora state, and another called La Línea, a faction of the Juárez Cartel with a strong presence in Chihuahua state.

The LeBarón family had for years denounced the presence of and threats made by organized crime groups in this lawless frontier. In 2009, two of their family members were kidnapped and murdered in Chihuahua. More recently, however, the family and Los Salazar in Sonora had reached a peaceful coexistence.

“Basically, it was ‘We won’t bother you if you don’t bother us,’” one family member told The Washington Post.

That all changed on November 4.

There were rumors about an escalating turf war in the months leading up to the deadly attack. Los Salazar in Sonora had allegedly asked the LeBarón family living in La Mora not to buy fuel from neighboring Chihuahua, which they argued was funding their rivals in La Línea, according to The Washington Post.

On the other hand, La Línea perceived the potential incursion of Los Salazar into Chihuahua as a direct threat to their operations, and decided to send a violent message in response, according to General Homero Mendoza, chief of staff of the Defense Secretariat.

With the attack, La Línea made it clear to their rivals in Los Salazar who controlled the highway crossing from Sonora into Chihuahua and eventually up to the U.S. border. Such routes are vital for smuggling drugs and migrants and facilitating other lucrative criminal economies.

InSight Crime analysis

The armed group alleged to be behind the massacre in Sonora emerged years ago as part of the outsourcing of security by Mexico’s most dominant cartels. While starting out as small family-based operations, these networks eventually expanded, leading to rising profits and the militarization of their drug trafficking activities.

Beyond securing their own areas of influence, the cartels were now also competing for control of drug smuggling corridors known as “plazas.” By winning a specific plaza, the dominant criminal group could charge a “piso,” or tax, to any other group moving contraband like weapons, humans or drugs through the area. This tax system provided another significant revenue stream.

To win these plaza battles, however, it was essential to have a greater number of loyal foot soldiers willing to fight to the death.

For the Tijuana Cartel, the Arellano Félix family looked across the border to members of San Diego’s Logan Street Gang, which they provided with weapons and tactical training. Members of the Mexican Airborne Special Forces Group were employed by the Gulf Cartel to be its enforcer wing, which later became known as the Zetas.

For its part, the Sinaloa Cartel used an internal faction of the group known as the Beltran Leyva Organization to form a mini army supported by smaller street gangs in areas the group controlled along the U.S.-Mexico border to combat its rivals. The Juárez Cartel hired current and former Mexican police officers to form La Línea, in addition to working with an El Paso-based street gang known as the Aztecas.

Over time, however, the structure of Mexico’s cartels changed and became less hierarchical. These armed wings developed more financial and decision making authority, as well as more autonomy. This in turn allowed them to expand outside of just providing security to engage in their own criminal activities, such as demanding extortion payments from local businesses and kidnapping.

The Zetas, for example, would eventually break away from the Gulf Cartel and transform into one of Mexico’s most ruthless criminal groups for a time.

La Línea also rose to prominence, even finding itself in the crosshairs of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI). The group’s former leader, Carlos Arturo Quintana Quintana, alias “El 80,” made it onto the bureau’s most-wanted list before he was arrested in May of 2018 after a blood-soaked criminal career that spanned nearly a decade.

Under Quintana’s command, La Línea bought off several municipal police forces and co-opted political operators in northwest Chihuahua to facilitate the Juárez Cartel’s drug trafficking operations through Ciudad Juárez and over the U.S.-Mexico border.

The ongoing turf war for control of key trafficking and smuggling routes in the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora dates back more than a decade.

But while some of the country’s so-called “small armies” have come and gone, La Línea’s brutal show of force against Los Salazar at the expense of the LeBarón family suggests they might be a critical piece of the Juárez Cartel’s plans to reign supreme once again in their former stronghold.

Reprinted from InSight Crime. Parker Asmann is a writer with InSight Crime, a foundation dedicated to the study of organized crime.