The former head of Mexico’s state oil company, Emilio Lozoya, was extradited from Spain more than a year ago over alleged bribes. But it was only after pictures of him eating Peking duck in an upscale restaurant triggered public outrage last month that prosecutors requested he be put into pre-trial detention.

President López Obrador called the lavish dinner “provocation.” Lozoya’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment, though local media has reported he denies wrongdoing. But for the government’s critics, the saga was illustrative of the Mexican authorities’ approach to fighting corruption: a strategy deeply influenced by politics and little to show for it.

Speaking at the United Nations this month — his second trip abroad in three years — López Obrador said that corruption in “all its forms” was “the biggest problem on the planet.” He added: “[In Mexico] we’ve applied the formula of banishing corruption and put the money saved into helping the people.”

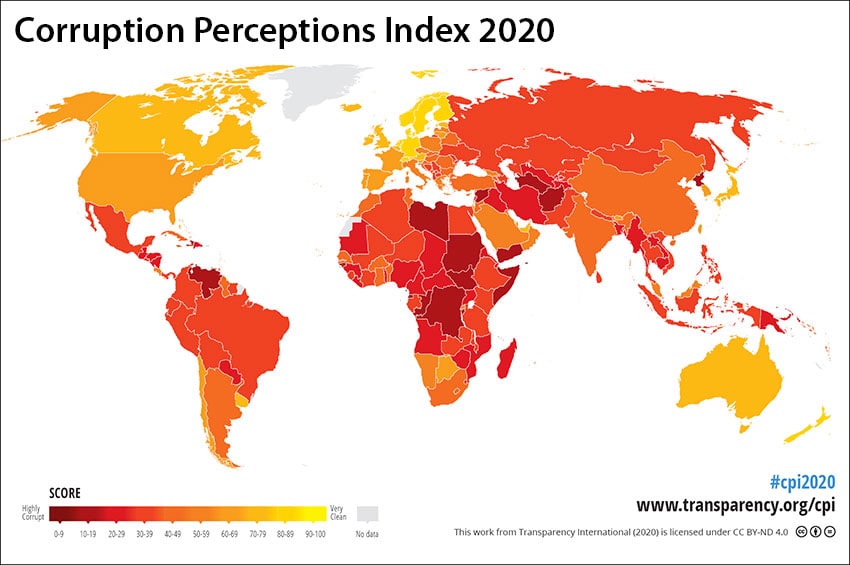

But analysts say there are few advances back home to shout about. Mexico has long been plagued by corruption, from payoffs to avoid speeding tickets to multimillion-dollar theft from public works contracts. Each year, Mexicans pay hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes to public officials for basic day-to-day paperwork such as starting a company or paying car taxes, statistics body INEGI estimates. Transparency International ranks Mexico in 124th place of 180 countries.

The federal anti-corruption prosecutor has only managed to secure two sentences for offences in more than 2 1/2 years in the job, one expert said. High profile cases are slow to advance.

“They don’t have a criminal prosecution policy . . . they choose cases for very unclear reasons,” said Eduardo Bohórquez, head of Transparency International in Mexico. “That arbitrariness is a bad sign in a prosecutor’s office.”

More worrying is the apparent pattern of exoneration of political allies and the pursuit of government critics and political opponents by both the administration and the nominally independent federal prosecutors.

“Before, corruption wasn’t being fought so that people in power could make money illegally,” said Miguel Alfonso Meza, a former civil society lawyer who now works in the municipal government of Monterrey, run by an opposition party. “Now corruption isn’t being fought to allow the group in power to consolidate itself but also to hurt democracy and pursue critics.”

López Obrador insists corruption is being fought in his government and that more than 200 criminal complaints have been made. “No one is being protected,” he said. The Attorney General’s Office did not respond to a request for comment.

The president’s image of being personally uninterested in amassing money for himself — something even many opponents believe is real — gives him credibility with voters on corruption. The problem is that institutions lack the independence or resources to sustain a real anti-corruption fight, activists said.

Thousands of accounts blocked by the Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF) have produced scant results in criminal cases. Earlier this month its head, Santiago Nieto, resigned after being rebuked by the president for his lavish wedding in Guatemala.

Other key oversight bodies like the Federal Auditor’s Office — part of the lower house of Congress — have presented far fewer criminal complaints during this administration than in previous years.

López Obrador has also undermined the National Anticorruption System — meant to co-ordinate different institutions — by calling it the “last straw” in a “pretend” anti-corruption fight.

“We still have the same problem, we don’t have institutions . . . that really work,” said Edna Jaime, director of think tank Mexico Evalúa. “The president hasn’t invested any of his political capital or resources, it’s not part of his project to strengthen these institutions.”

At one of his daily morning press conferences last month, López Obrador promised to publish details of those who have been sanctioned or accused of corruption. The subsequent release said thousands of officials had been barred from government and hundreds of criminal complaints had been made, but didn’t mention a single criminal conviction.

© 2021 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.