A disclaimer: as I write these lines, I know not where I am heading nor how it will end.

There are no other two Latin American countries as alike or as endeared to each other as Colombia and Mexico. We were even neighbors exactly 200 years ago.

In 1821, 11 years after we began fighting for our independence from Spain — Colombia on July 20, 1810, and Mexico on September 16 of the same year — we shared a border that today is the boundary between Costa Rica and Panama. This was when México, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica were part of the (short-lived) First Mexican Empire that had Mexico City as its capital and when Colombia, Panamá, Venezuela and Ecuador comprised the (ephemeral) Great Colombia, for which the capital was Bogota.

There are probably no other two nations as blessed by nature and as cursed for their proclivity for living on the edge: Colombia, the one with a War of the Thousand Days and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude; and Mexico, the one with the Mexican Revolution and Octavio Paz’s The Labyrinth of Solitude.

Both countries are privileged by their geographies, natural resources, histories, cultures and public-spirited peoples yet beleaguered by poverty, violence, corruption, drug trafficking and political demagoguery.

Blessed are we both by our two coastlines — the Pacific and the Atlantic — and their marine natural resources, as well as the rainforests of the great Lacandon Maya jungle in Chiapas, and Colombia’s part of the vast Amazon rainforest and the indigenous peoples that live there.

Blessed are both countries by the mighty Amazon and Caquetá rivers in Colombia and the Usumacinta and Grijalva rivers in Mexico. Mexico has part of the Mesoamerican Reef, the world’s second largest barrier coral reef, and Colombia is home to 60% of Earth’s stunning páramos — those neotropical high-altitude ecosystems that extend between the upper tree line and the perennial snow border (3,200 to 5,000 meters above sea level), which creates a sky island archipelago.

Blessed are we both for having 1.7% of the planet’s total area, where together we are home to 20% of Earth’s biodiversity. Colombia has the highest number of species of birds, orchids and colorful butterflies on the planet, and it is second in diversity of amphibians and vascular plants.

Mexico has the highest number of pine species and is second in diversity of reptiles, third in mammals and fifth in amphibians.

Volcanoes, dead and alive, also bless us: Pico de Orizaba, Popocatépetl, Iztaccíhuatl, Nevado de Toluca and Malinche (“the one with the blue slopes” in Nahuatl) and Nevado del Ruíz, Nevado de Tolima, Nevado de Huila, Galeras and Puracé (“the mountain of fire” in Quechua).

We are also blessed with ancient indigenous cultures — Aztec, Maya and Olmec, and Muisca, Tairona, and Inca. Mexico is the world’s fifth most linguistically diverse country (it has 364 living languages), and 7.4 million Mexicans speak an indigenous language while

Colombia has 65 living languages and 1.4 million Colombians speak an indigenous language.

Mexico is the country with the most Spanish-speaking people, while Colombia is second. Spain is third.

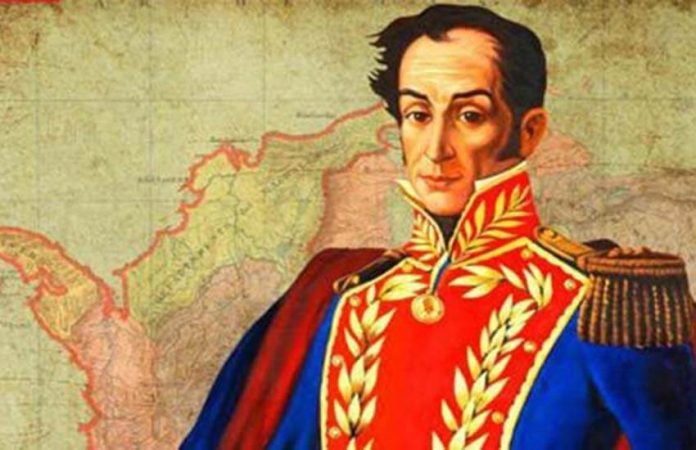

In 1821, Colombia was the first country to recognize Mexico’s independence. In fact, the first congratulatory message Mexico got as a free nation was from Simón Bolivar, el Libertador himself, on behalf of the Gran Colombia. The two countries established diplomatic relations on October 3, 1823, with the signing of the Treaty of Friendship.

That same year, Colombia and Mexico together laid out the basis for the Hispanic American asylum doctrine in a treaty of nonextradition for political crimes created in order to protect the heroes who had launched independence movements in the region.

Since Spain didn’t recognize the independence of any of its colonies or former colonies in the Americas, in 1823, Colombia fostered an alliance with Mexico against Spain’s aggressions with a flotilla of cannon-carrying ships to harass Spanish maritime trade in the Caribbean.

They also incited Cuba’s quest for independence — as documented in Germán de la Reza’s 2015 essay published in the journal Secuencia, “The Attempt to Integrate Santo Domingo into Gran Colombia (1821–1822).”

Those bonds between Colombians and Mexicans are even stronger today: Mexico is the third-highest source of visitors to Colombia, and Colombia is Mexico’s second-highest source of tourists. Colombians are the most numerous Latin Americans to study in Mexican universities.

Colombia is Mexico’s second most important Latin American commercial partner, and Mexico is Colombia’s third most important import partner, and sixth in terms of direct foreign investment. Mexico is the second largest Latin American economy and Colombia is fourth.

So if those are our blessings, what are our curses?

Some people say that Colombians and Mexicans are innately violent and corrupt, respectively. Nonsense.

However, it’s true that Colombia’s fratricidal wars between conservatives and liberals during 1946–1958 left 300,000 dead and 2 million displaced — at the time, nearly a fifth of the country’s population. From 1812 to 1902, Colombia faced thousands of deaths and the havoc caused by nine civil wars.

And since the 1960s, the armed conflict between the government and the left-wing guerrillas, the right-wing paramilitaries and the drug cartels and other organized crime has killed more than 220,000 Colombians. Millions of families were devastated.

In Mexico, it has been estimated that 1 million people died between 1910 and 1920 in the wars of the Mexican Revolution. It was the continent’s deadliest civil war and the world’s ninth deadliest.

More recently (2006–2021), Mexico’s war against drug cartels and organized crime has resulted in the death of more than 372,000 Mexicans, leaving hundreds of thousands of orphans and widows.

And let us not forget that both Colombia and Mexico are globally among the countries where the most environmental defenders have been killed.

According to the United Nations, Colombia is currently the country with the most internally displaced citizens due to war, violence, and persecution: 8.3 million people (10% of the world’s total), including millions of children, have been forced to abandon their homes, leaving everything behind, resulting in even more displaced people than in Syria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Sudan, Mozambique, Yemen or Afghanistan.

Paradoxically, Colombia also ranks second on the planet in accepting refugees (it is home to 7% of the world’s total, including 1.7 million Venezuelans). And in August of this year, Colombia and Mexico were the first Latin American nations to offer asylum to refugees from Afghanistan.

As of December 2020, Mexico had 357,000 internally displaced people, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council. Regrettably, our current policy on refugees is contradictory, to say the least.

On the one hand, Mexico was the first Latin American country to take refugees from Afghanistan (some 500 so far), but on the other hand, we seem to be turning our homeland into a despicable wall to stop refugees who are desperately fleeing hunger, crime and the impacts of climate change in Central America and the Caribbean.

Finally, two of the worst and most deeply rooted curses in Mexico and Colombia are their inequality and corruption. According to the United Nations Development Programme, between 2000 and 2019, Latin America was the second most inequitable region, only after Sub-Saharan Africa. And both Mexico and Colombia are among the countries with the most income concentration among the fewest people.

Mexico is Latin America’s second most inequitable country and Colombia is its sixth. Ten percent of Mexico’s population holds 59% of the national income, while 1% of Mexican citizens hold 29% of the nation’s income. And Transparency International, a global coalition working in over 100 countries to end corruption, has reported that Mexico is 124th and Colombia 92nd on their list of corrupt countries among 180 analyzed (the higher the position, the higher the corruption index).

As I admitted at the beginning of this essay, I don’t know how to close these thoughts.

That is why, with humbleness, I would only share the words that my Colombian and Mexican compatriot Gabriel García Márquez said in Mexico City on October 22, 1982, after receiving the Order of the Aztec Eagle, Mexico’s highest distinction to a foreigner:

“It is not, then, my second homeland, but another one, different than was given to me without conditions and without contesting the love and fidelity I profess for my own homeland, and the nostalgia with which she demands both from me without truce … My sons have grown here; I have written my books here; I have planted my trees here. … Thank you for these open doors. May they never be closed, please, not under any circumstances.”

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and is the former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.