Tijuana was the most violent municipality in Mexico in the first five months of 2021 in terms of sheer homicide numbers, federal data shows.

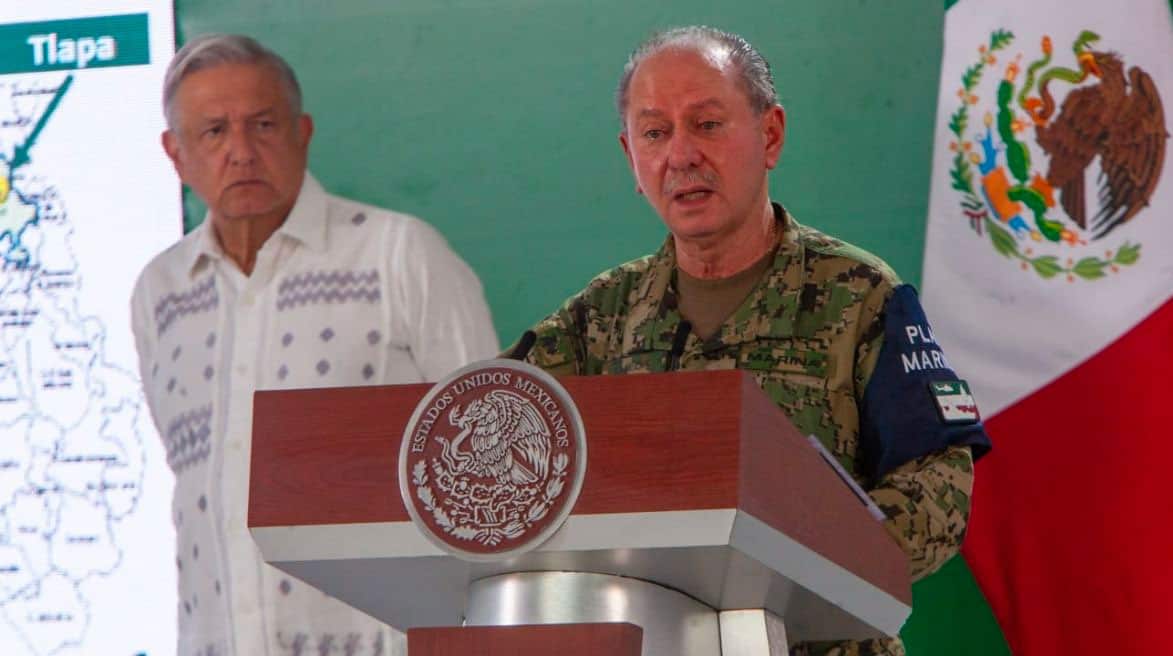

Navy Minister Rafael Ojeda presented a graph at President López Obrador’s news conference on Monday that showed the 50 most violent municipalities between January and May this year.

Tijuana, Baja California, ranked first with 749 homicides for an average of 150 per month or five per day. Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, was second with 515 homicides between January and May followed by León, Guanajuato, 295; Cajeme (Ciudad Obregón), Sonora, 225; and Acapulco, Guerrero, 197.

In sixth to 10th place were Fresnillo, Zacatecas, 190; Guadalajara, Jalisco, 186; Chihuahua city, 158; Ensenada, Baja California, 158; and Celaya, Guanajuato, 151.

Among the other 40 municipalities on the list were three Mexico City boroughs – Iztapalapa, Gustavo A. Madero and Venustiano Carranza – and Ecatepec, Naucalpan, Tlalnepantla, Nezahualcóyotl and Cuautitlán Izcalli, which are in México state but part of the greater metropolitan area surrounding the capital.

In addition to Guadalajara and Chihuahua city, nine state capitals were among the 50 most violent municipalities in the first five months of the year. They were Culiacán, Sinaloa; Morelia, Michoacán; San Luis Potosí city; Hermosillo, Sonora; Mexicali, Baja California; Monterrey, Nuevo León; Cuernavaca, Morelos; Zacatecas city; and Puebla city.

Other notable cities that appeared on the list included Benito Juárez (Cancún), Quintana Roo; Tecate, Baja California; Irapuato, Guanajuato; Uruapan, Michoacán; Manzanillo, Colima; Nogales, Sonora; and Reynosa, Tamaulipas.

The 16 most violent municipalities all recorded more than 100 homicides between January and May, while those ranked 17th to 44th registered at least 50. The 45th to 50th most violent municipalities saw between 47 and 49 homicides in the first five months of 2021, a period in which Mexico recorded 14,243 murders – a 2.9% decline compared to the January-May period of 2020.

The presentation of the graph came just days after López Obrador told Morena party governors and governors-elect that the federal government will concentrate its anti-crime efforts on the 50 municipalities with the highest rates of insecurity.

Ojeda also presented a graph that ranked the 32 states according to the number of homicides recorded between December 2018 – the month the current federal government took office – and May 2021.

Guanajuato ranked first with 7,646 homicides in the 30-month period followed by Baja California, 6,622; México state, 6,169; Chihuahua, 5,462; and Jalisco, 4,791.

Eleven states – the five above plus Michoacán, Guerrero, Veracruz, Sonora, Mexico City and Puebla – were above the national average of 2,277 homicides, while the other 21 were below the average. The five states with the fewest homicides in the period were Yucatán, 106; Baja California Sur, 171; Aguascalientes, 193; Campeche, 194; and Tlaxcala, 320.

On a per capita basis, Colima was the most violent state in the first 2 1/2 years of the government’s six-year term with 199.9 homicides per 100,000 people, according to another graph presented by the navy chief. Baja California ranked second with a per capita rate of 175.7 followed by Chihuahua, 146; Guanajuato, 124; and Zacatecas, 111.6.

Yucatán maintained its status as the least violent state on a per capita basis with just 4.6 homicides per 100,000 people between December 2018 and May 2021. Aguascalientes was the second least violent followed by Coahuila, Querétaro and Durango.

Here are Mexico’s 50 most violent municipalities:

- Tijuana, Baja California

- Juárez, Chihuahua

- León, Guanajuato

- Cajeme, Sonora

- Acapulco, Guerrero

- Fresnillo, Zacatecas

- Guadalajara, Jalisco

- Chihuahua, Chihuahua

- Ensenada, Baja California

- Celaya, Guanajuato

- Zamora, Michoacán

- Culiacán, Sinaloa

- Morelia, Michoacán

- Benito Juárez, Quintana Roo

- San Pedro Tlaquepaque, Jalisco

- Tecate, Baja California

- Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Jalisco

- Ecatepec de Morelos, México

- San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí

- Irapuato, Guanajuato

- Iztapalapa, Mexico City

- Hermosillo, Sonora

- Mexicali, Baja California

- Uruapan, Michoacán

- Zapopan, Jalisco

- Tonalá, Jalisco

- Iguala de la Independencia, Guerrero

- Manzanillo, Colima

- Monterrey, Nuevo León

- Apaseo el Grande, Guanajuato

- Salamanca, Guanajuato

- Guaymas, Sonora

- Nogales, Sonora

- Gustavo A. Madero, Mexico City

- Cuernavaca, Morelos

- Guadalupe, Zacatecas

- Naucalpan de Juárez, México

- Jacona, Michoacán

- Zacatecas, Zacatecas

- Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco

- Caborca, Sonora

- Reynosa, Tamaulipas

- Tlalnepantla de Baz, México

- Nezahualcóyotl, México

- Puebla, Puebla

- Cuautitlán Izcalli, México

- San Luis Río Colorado, Sonora

- Venustiano Carranza, Mexico City

- Juárez, Nuevo León

- Yuriria, Guanajuato

Mexico News Daily