This week in Mexico, President Claudia Sheinbaum defended her government’s transfer of 37 alleged cartel members to the United States as a “sovereign decision” even as opposition lawmakers questioned the legality and timing. Nine thousand kilometers away in Davos, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney declared a “rupture” in the international order and announced new trade partnerships — prompting Sheinbaum to dispatch her Economy Minister to Washington to smooth over relations before the formal review of North America’s free trade deal. Meanwhile, Spanish King Felipe VI shook hands with Mexico’s representatives at the FITUR tourism fair in Madrid — the first contact between the Spanish crown and Mexican officials since 2019’s diplomatic freeze. As FAA warnings alerted U.S. pilots to possible military activity over Mexican airspace and domestic tourism stagnated for the second consecutive year, the week illustrated Mexico’s simultaneous push for global prominence and struggle to maintain regional stability.

Didn’t have time to read this week’s top stories? Here’s what you missed.

Security and bilateral cooperation

The week’s most significant development came Tuesday when Mexico transferred 37 alleged cartel members to the United States in the third major prisoner handover since President Claudia Sheinbaum took office. Among those sent north were Ricardo González Sauceda, identified as a regional leader of the Northeast Cartel, and Pedro Inzunza Noriega, father of a senior Beltrán Leyva Organization figure. The transfer brings to 92 the total number of high-level criminals extradited during the current administration.

Mexico sends 37 alleged criminals to US in third major prisoner transfer

Security Minister Omar García Harfuch emphasized that all transferees were wanted by U.S. authorities and that Mexico received assurances the death penalty would not be sought against any of them. The move appeared designed to demonstrate cooperation amid mounting pressure from the Trump administration, which has recently threatened military strikes against cartels operating in Mexico.

President Sheinbaum defended the decision during Wednesday’s morning press conference, calling it a “sovereign” choice made in Mexico’s interests rather than a capitulation to U.S. pressure. Critics in opposition parties questioned whether proper legal procedures were followed, with some lawmakers demanding greater transparency about the terms of the transfers.

The bilateral security relationship also made headlines when Mexican authorities announced the arrest of Alejandro Rosales Castillo, an FBI “10 most-wanted fugitive” sought since 2016 for murdering his former girlfriend in North Carolina. Captured in Pachuca, Hidalgo, the arrest demonstrated ongoing cooperation between Mexican and U.S. law enforcement agencies.

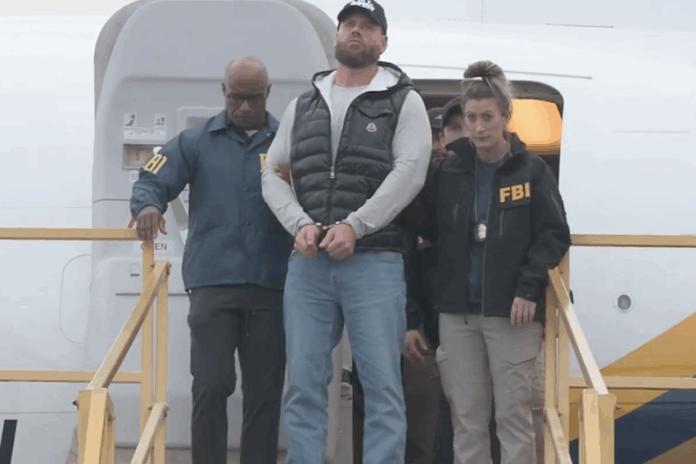

Thursday brought an even more dramatic capture when former Olympic snowboarder Ryan Wedding turned himself in to authorities in Mexico City. Wedding, a Canadian who competed in the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics, allegedly ran a transnational cocaine network that imported 60 tonnes annually while living a “colorful and flashy” lifestyle in Mexico for over a decade. FBI Director Kash Patel flew to Mexico City to personally escort Wedding and Castillo back to California, calling Wedding “a modern day Pablo Escobar.”

FBI Director Kash Patel announces the capture of Ryan Wedding, a former Olympian and accused drug lord, after years on the run.

“Just to tell you how bad of a guy Ryan Wedding is, he went from an Olympic snowboarder to the largest narco trafficker in modern times,” Patel said.… pic.twitter.com/GZgAFQqvd5

— CBS News (@CBSNews) January 23, 2026

Adding to the week’s security-related news, questions arose about a U.S. military plane that landed at Toluca airport Saturday. During Monday’s press briefing, Sheinbaum clarified that the flight had been authorized in October for training purposes, with Mexican security officials boarding the aircraft to travel north for a month-long program. Security Minister García Harfuch elaborated during Friday’s conference that U.S. Northern Command had invited Mexican personnel to a Mississippi base for tactical training in shooting and investigation. While Sheinbaum acknowledged it would have been preferable to use a Mexican military plane, she stressed no U.S. troops had entered Mexican territory.

Aviation alerts raise concerns

The Federal Aviation Administration issued seven NOTAMs (notices to airmen) Friday urging U.S. pilots to “exercise caution” over Mexico’s Pacific coast and the Gulf of California due to possible military activities and satellite navigation interference. Mexico’s response characterized the warnings as precautionary, with the Ministry of Infrastructure, Communications and Transport asserting there were no operational implications for Mexican airspace.

The FAA alerts, valid through March 17, sparked speculation about potential U.S. military operations in the region. However, Sheinbaum maintained Sunday that no U.S. military action was occurring in Mexican territory, pointing to coordination between Mexican authorities and the U.S. Embassy to clarify the situation.

International diplomacy and trade tensions

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Mexico’s presence addressed both environmental and economic priorities. Environment Minister Alicia Bárcena used the platform to stress urgent climate action, warning that current efforts remain insufficient. She outlined Mexico’s development of three circular economy parks and its commitment to achieving net-zero emissions, while seeking international partnerships to accelerate the country’s green energy transition.

Perhaps more consequential for Mexico’s economic future were remarks by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, whose speech Sheinbaum publicly endorsed during Wednesday’s press conference. Carney’s assertion that the rules-based international order is undergoing a “rupture, not a transition” — with veiled references to U.S. President Donald Trump’s policies — could signal challenges ahead for the USMCA trade agreement’s upcoming review.

The escalating tensions between Trump and Carney prompted immediate action from Mexico. After Trump called Canada ungrateful in his Davos speech, Sheinbaum promised Mexico would hold the deal together as Economy Minister Marcelo Ebrard went to Washington to smooth ruffled feathers. “We are going to work so that it doesn’t break,” Sheinbaum said of the USMCA deal.

Adding to economic developments, the Mexican peso strengthened to below 17.5 per U.S. dollar this week — its strongest level since 2024. Banamex economists predicted the “superpeso” could sustain strength for the next two years, offering a rare bright spot amid economic uncertainties.

Tourism and cultural promotion

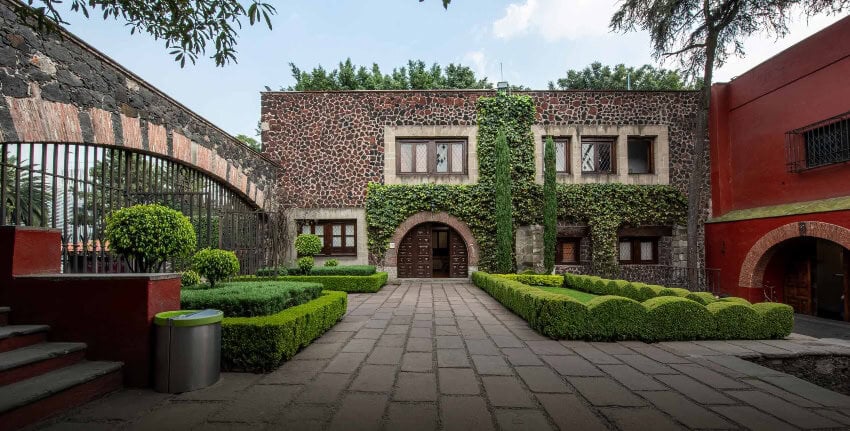

Mexico took center stage at Madrid’s International Tourism Fair (FITUR) this week as the event’s partner country. The country’s comprehensive showcase featured all 32 states, with cultural performances including Oaxaca’s Guelaguetza and Michoacán’s Danza de los Viejitos drawing international attention. Mexican artist César Menchaca created a striking Huichol-inspired interpretation of Madrid’s iconic Bear and Strawberry Tree monument, placed prominently at Puerta del Sol.

FITUR was also the site of a significant diplomatic moment when Spanish King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia visited Mexico’s fair pavilion — the first contact between the Spanish monarchs and Mexican officials since former President López Obrador’s 2019 demand for an apology for the Conquest. Sheinbaum characterized the visit as “symbolic,” noting the royals’ interaction with Indigenous representatives could help “heal wounds.”

FITUR also yielded concrete results for Mexican states, with Guanajuato Governor Libia García announcing that Air Europa will establish direct flights from Madrid to the Bajío International Airport starting this year. The new route is expected to strengthen international connectivity and boost European tourism to central Mexico.

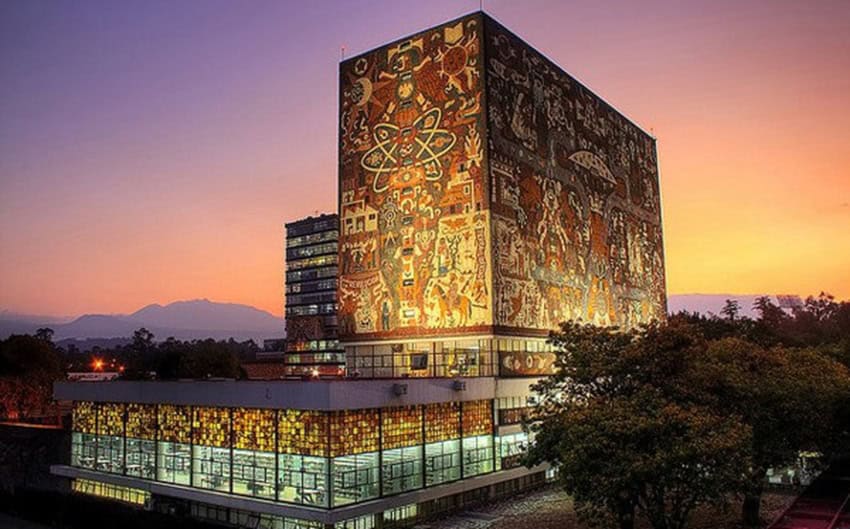

The promotional effort aligns with the Sheinbaum administration’s ambitious goal of positioning Mexico among the world’s five most-visited destinations by 2040. However, this aspiration faces headwinds from stagnating domestic tourism, which saw essentially flat growth in 2025 after declining in 2024. Experts attribute the trend to a weakening economy, reduced household purchasing power and security concerns affecting certain destinations.

Domestic health initiatives

On the home front, President Sheinbaum announced plans during Tuesday’s press conference to issue universal health care identification cards to all Mexicans, representing a step toward integrating the country’s fragmented public health system. The cards will link to electronic medical records and allow citizens to identify their health care provider while facilitating future cross-institutional treatment.

The registration process, costing approximately 3.5 billion pesos, will begin March 2 with 14,000 Welfare Ministry workers staffing registration modules nationwide. The initiative comes as measles continues spreading throughout all 32 states, with over 7,100 cases and 24 deaths reported in the past year despite vaccination efforts.

Judicial reform questions persist

Questions about Mexico’s controversial judicial reform resurfaced during Friday’s press conference in Veracruz when a reporter asked Sheinbaum whether the Supreme Court showed bias toward the ruling Morena party. The question followed an El Universal report finding that the newly elected Supreme Court — whose nine justices won their seats in Mexico’s first judicial elections last June — had ruled in favor of government-backed reforms at least six times without a single ruling against them. Sheinbaum deflected, saying the court itself would have to answer such questions, while noting that sessions were now public rather than conducted “in the dark” as before.

Weather and natural conditions

As the week ended, Mexico’s National Meteorological Service issued winter weather alerts for northern states, warning of the third major winter storm of the season. Border states including Baja California, Sonora and Chihuahua faced predictions of significant temperature drops, strong winds and heavy rainfall, with possible snow or sleet. The warnings coincided with a potentially historic winter storm system affecting the United States from the Texas Panhandle to the Northeast.

Looking ahead

As the USMCA review approaches, Mexico faces critical decisions about how to navigate an increasingly complex North American relationship. The week’s events — from prisoner transfers demonstrating cooperation to aviation alerts suggesting ongoing tensions, from FITUR’s diplomatic breakthroughs to Davos clashes threatening trade stability — illustrate the delicate balance required. The Sheinbaum administration must maintain sovereignty while strengthening partnerships essential to economic growth, all while addressing domestic challenges from public health to tourism sector weakness and adapting to shifting geopolitical realities where Canada pursues alternatives to U.S. dependence. The coming weeks will test whether Mexico can successfully walk this tightrope.

This story contains summaries of original Mexico News Daily articles. The summaries were generated by Claude, then revised and fact-checked by a Mexico News Daily staff editor.