It’s always the same story. The election, the passion, the waving of the fist, the belief. Mr. ‘manifesto-of-change’ stands on the steps of the town hall, in the parliamentary chamber, or in front of the presidential residence, and professes a revolution in government. An end to corruption, an overhaul of burgeoning bureaucracy, a new way forward for the Mexican people.

Then comes the inevitable descent, often more insipid than dramatic, and so the process begins again.

Mexico is bored stiff, more than bored: disdainful at best, furiously distrustful at worst. The country sees this on a daily basis, the self-perpetuating actions and processes of institutionalized politicians, the literal systemic nature of the problem. But what is rarely seen or acknowledged is that the beginning of a sea change is already quietly rolling through society.

This isn’t a new phenomenon, it fact it’s been around us the whole time, but is now perhaps starting to reach (whisper it) a critical mass; and these initiatives are harder to identify because inherent in their genus is not placing importance on the validation of being lauded. Moreover, the structures inherent in these parallel systems are civilian-led, structured from the bottom up allowing for a foregrounding of real people over grand projects, grass-roots development and concerted local participation over bloated grand designs.

A particularly interesting individual in this context is Anielka García Villajuana, president of the independent non-profit Patronato de la Ciudad de Campeche. The Patronato was set up 20 years ago to oversee Campeche’s transition to a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but under García has morphed into a multi-directional body, which while retaining that initial focus now also works across wide-ranging socio-environmental programs in the city and its environs.

Perhaps the greatest signpost to this evolution is García’s instinct for people: “There really are good people everywhere, all too often fighting a daily fight against the odds just to be allowed to get on with things. We try to work alongside existing projects and just give them agency. None of it can be about us, we’re just here to say: ‘We believe in you, how can we help?’ And then get our hands dirty too.”

Projects can take the form of environmental initiatives, cultural events, educational workshops, even medical programs. Essentially, the aim is not to introduce a higher standard of living, fix a road with an x amount of net spend or provide a particular service, but to participate intrinsically alongside and within society, to act and encourage action across existing progressive, civic endeavors and in that way to encourage more change-making from the bottom up. It’s not a physical evolution of society, but a cultural one.

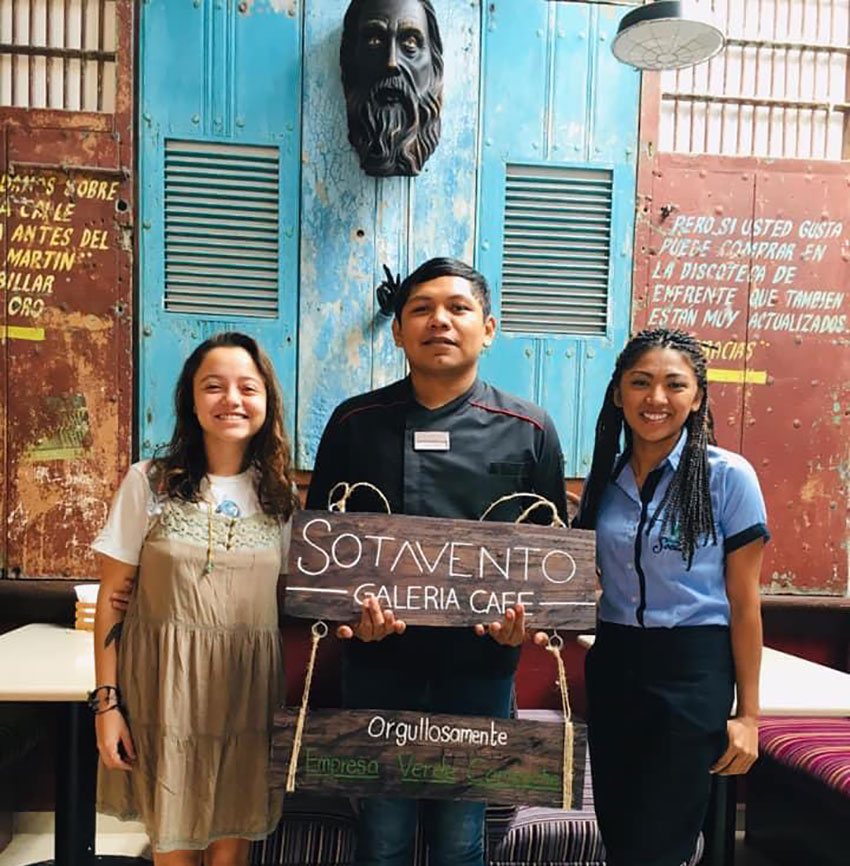

Obvious to all is that there are gaps in governmental works in Campeche, and where these demonstrate their slack, García has picked it up, working in areas where there is often a clear absence of state systems, such as sustainability in businesses. Enter Empresa Verde, an expanding citywide collection of sustainable businesses, working on everything from intelligent purchasing to elimination of single-use plastics to waste separation and reuse.

This then feeds into El Campanario, a piece of land on the outskirts of the city loaned by local businessman Juan Pérez Hernández that serves as a not-so-final destination for organics from these businesses and that also doubles as a space for urban growing courses, animal rescue and organic small-scale farming. This process has been infrastructurally supported by other local businesses including El Surco S.A. de C.V., which has helped clear land, transport materials, and much more.

Not to mention the now-famous “Doctor en Bici,” Luis Fernando Hernández, who visits marginalized communities on weekends to provide free medical consultations. “He is doing such great work,” says García.

“Nothing at all needed changing, but we realized we could help by encouraging people to donate medicines and be a reception center for these, so that’s what we’re doing. Not much really.” Her tone, unsurprisingly, is self-deprecating.

Essentially — perhaps without even realizing it — García, who is emphatically not alone in working this way, is fracturing a system that has failed so many. “Traditionally authorities would see an existing project which was working,” she says, “and — at worst — want to co-opt it, or at very best just get in the way. What very rarely happens, but in my view is exactly what we should be doing, is giving amazing people and projects licence to run … to just get on with things. It should involve us all sweating and bleeding together, because that’s how community comes together, and the better societies are formed.”

García’s words ring true from a local governmental level all the way through to national leadership. Normal processes involve each new political remaking and relaunching for ego’s sake, there is no vested interest in continuation or maintaining what works, rather pretending everything that came before was a waste of time, scorching the earth and presenting yourself and your new initiatives as those of the returning King.

Placing the people at the center of the change is quietly radical, but it’s also the next logical step. While the interventionist state may have its place (something that García herself understands), it perpetuates the resilient legacy of colonialism, an era in which something would be adopted, changed or quashed on the whims of plutocrats, not the affected people. At least remnants of this attitude linger on today, and the only way to reject a recklessly interventionist patronage seems to be in its restructuring, and the re-centering of the community.

On the face of it, it appears as though we have seen something similar enacted on a national scale before, through Mexico’s National Anti-Corruption System (NACS). Despite being introduced by the government, it is comprised entirely of non-governmental interests. The organization is essentially presided over by a board of civilians, with the goal being to kick the entire political football from the field of interests.

But this theorized structure hasn’t yet been able to yield the fruits imagined of a truly democratized institution, likely because generating an anti-system just ends up being co-opted by existing paradigms — it remains in discourse with the structures that created it. It may give the illusion of purity, but inevitably leaves the door wide open to the influences of the government they exist to challenge.

The NACS framework seems on face value to be a wider extrapolation of García’s networks, but it falls short in how it came to be and therefore its cross-societal structures. These initiatives cannot be brought to life from one place, they have to come from everywhere, and consequently be cross-societal, multi-sectoral, and a truly amorphous network. We can’t just replace the sullied with the unsullied. Instead, our answer may need to mirror the complexity of the society it seeks to unify.

Countless humble pioneers working in this way across the country display a clear message: they are here to help and get things done, but not by fixing the government’s mess, instead by existing in parallel. Such a philosophy is coming to be productive in Mexican society; it encourages change-makers and innovators, but recognizes that the political powers still have a responsibility to work with them and get their own house in order.

Meanwhile, behind closed doors, right across the country, incredible things are happening; pioneers of change continue to toil below our radar, quietly demonstrating the raw power of people.

Writer Jack Gooderidge is based in Campeche.