Righting the historical wrongs enacted by colonizers, or a politically correct enforced rewriting of history? Rape and pillage of artifacts, or legitimately acquired entities that are no longer owned by the original maker — the case with the vast majority of objects on Earth?

Whatever the truth of it, the ongoing project to create a national identity based on antiquity is felt in few places as keenly as it is in Mexico, where the overthrow of the ancient civilizations meant the foreign acquisition of both a material cultural heritage and an identity tied to one of the oldest civilizations in the world.

As a part of this, Mexico has been struggling for the return of its archaeological goods from museums and collections across Europe and the United States, especially recently under the populist López Obrador government.

Internationally, too, debates surrounding the contents of museums have increased in intensity over recent years. Calls to restore cultural property to places of origin are increasingly being felt by institutions whose history is steeped in colonial practice and old money.

The question of cultural restitution is undoubtedly a complex one. Where efforts seem to be underway, there is a significant backlash not just from the old, “colonial” lobby — that is to say those who seek to influence policy in favor of retaining the power imbalance between former colonies and their colonizers — but also those who more straightforwardly argue that items end up in museum collections for a variety of reasons which do not include looting and theft, including legitimate gifting.

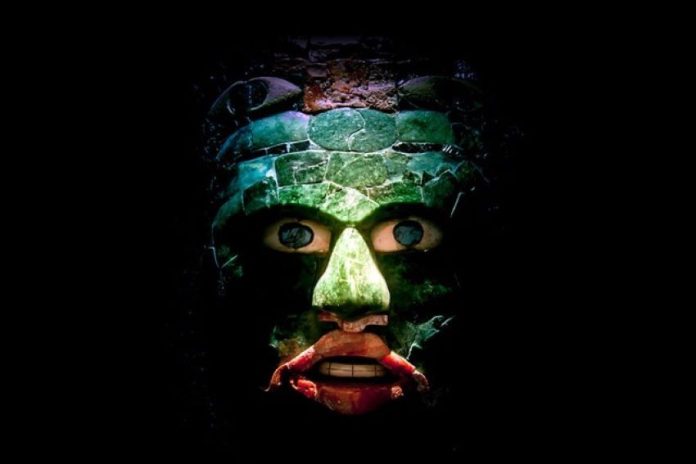

A recent and very literal figurehead in this debate is the Quetzalcóatl Headdress, often known as Montezuma’s Headdress. Standing at over a meter high, the piece is the ongoing subject of such back-and-forth reprisals.

Dubiously purported to have been given to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés as part of a collection of 158 items by Montezuma himself, the last Aztec emperor, the headdress is considered one of the most important historical relics in Mexico and has long been the subject of tensions between Mexico and Austria, given that several unsuccessful requests for its return have been made.

Moreover, some museum professionals argue that the headdress is “better off” left in the care of the museum in which it resides.

The curator of Vienna’s Museum of Ethnography has made claims that the headdress cannot be moved because it is too fragile to travel, suggesting that even loaning it to Mexico would risk damages that might destroy the object.

A rebuttal to this statement regularly points out that most of the professionals making judgments such as this are white European men of a similar age and education who, it would seem, either cannot or will not acknowledge that disputes over cultural property are part of a broader project — one that asks that former colonial powers take ownership of their histories.

The decolonization of museums — that is to say clearly stating the ways they have benefitted from a colonial past and addressing ongoing power imbalances — is increasingly being recognized as a necessary aspect of contemporary museum work. The movement toward more critical representations of empire within the very institutions that empire built has spawned some attempts at providing extra context for items in collections — namely pointing out where an item is linked to a part of the colonial past.

Occasionally, attempts are made by museums to circumvent the issue of decolonization and the restitution of cultural artifacts by “diversifying” their collections. At best, these attempts still beg the question, is it enough? At worst, they are tokenistic gestures to mollify protesters that do little to combat the underlying dominant narratives of historical supremacy.

A demonstrably multifaceted issue to begin with, it is exacerbated by the ongoing pillaging of historical sites across the world, especially in Mexico. According to the Institute of Anthropology and History, more than 40% of Mexico’s archaeological sites have been looted despite laws meaning that perpetrators face up to 12 years in prison if caught stealing objects and attempting to export them.

Prosecutions are rare, however, due to lax oversight and corruption among officials. As a result, a large number of looted items end up in Europe and the United States, making their way into collections from which they may only be extricated by complicated legal battles.

On the flip side, there are rare instances of international cultural cooperation that testify to the possibilities of repairing some of the damage done by earlier generations.

One such example is the repatriation of a Mayan urn, to the Museo de los Altos in Chiapas, from where it is believed to have originated, alongside a twin urn already on display there. For the past half a century, it has resided at Albion College in Michigan.

The urn came into the college’s possession as part of a bequest by alumnus Marvin Vann, who spent many years in Mexico mapping areas such as Chiapas and helping himself to native artifacts. Upon his death in 2003, Albion College received a large collection of photographs, papers and artifacts, including the urn.

The repatriation of the stolen urn is an important recognition that the history of a culture or place is intrinsically tied to the communities who live there and that any objects or stories originating in these places are rightfully theirs.

As these questions creep forth in the international consciousness, the future of museums increasingly comes into question. Whatever the fate of artifacts held by institutions for centuries, there is no doubt that museums must face, head-on, the colonial power imbalances in which their very existence is steeped.

Shannon Collins is an environment correspondent at Ninth Wave Global, an environmental organization and think tank. She writes from Campeche.