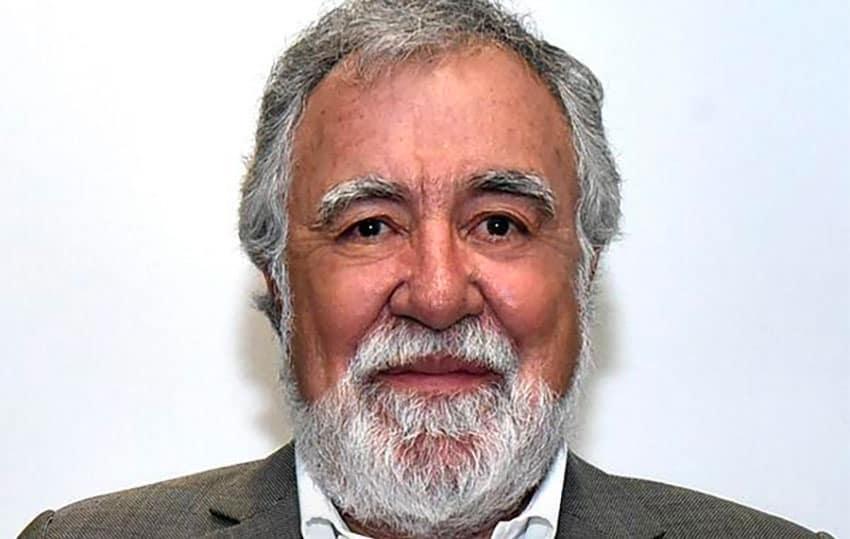

The August 19 jailing of former attorney general Jesús Murillo in connection with one of the most disturbing atrocities in recent Mexican history has two possible interpretations, neither of which is encouraging.

One is that the top law enforcement officer in the 2012-2018 Peña Nieto administration was complicit in the September 2014 disappearance and presumed murder of 43 teachers college students in Iguala, Guerrero – the very crime he was in charge of investigating.

The other is that the arrest has more to do with politics than evidence, that it panders to the incumbent president’s supporters while exacting revenge on his predecessors, and confirms his detractors’ suspicions that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) is at heart an authoritarian.

Both are realistic at this point, but a third, alas, is not. There’s little chance that this action, bold as it is, will lead to a credible explanation of what happened that night in Iguala, and with it some kind of justice for the victims and closure for their families.

Murillo faces three accusations — torture, forced disappearance, and what amounts to obstruction of justice or coverup. The general feeling of the punditocracy — mostly anti-AMLO, it should be noted — is that only the torture charge might stick, presumably based on the unspoken assumption that everybody does it.

The other two? Not so much. The commentators mostly agree that to convict the former attorney general of forced disappearance would require strong evidence that he personally participated in it. As for the coverup, the prosecution must overcome the obstacle that Murillo’s November 2014, official version of the events in Iguala, which prosecutors cite as purposefully misleading, is seen to have much in common with the current government’s version.

Even Reforma’s Sergio Sarmiento, one of the more cautious members of the commentariat, had this to say: “If the charges were just for torture, perhaps they’d make sense. But to accuse Murillo of forced disappearance is without rhyme or reason. And to try him for giving a version of the events that fundamentally coincide with what the (current) prosecutor’s office maintains is perverse.”

Of course, the legitimacy of the charges remains to be seen. For now, however, few observers dispute that there’s a certain amount of political propaganda involved with Murillo’s detention. Some say the whole thing is nothing but actos mediáticos — a useful Mexican expression for a “media show,” though it might be more bluntly translated as “publicity stunt.”

For example, they say, a simple citation might have been sufficient for a 74-year-old former public servant in poor health who seldom left his house. Instead, agents from the FGR (the Attorney General’s Office, a more autonomous version of the office, then called the PGR, that Murillo had headed up) moved into his neighborhood, supported by the navy, to take him in a high-profile operation.

There was a certain Keystone Cops element to the proceedings. According to the online news site Animal Político, the agents started escorting their target’s brother to custody before realizing their mistake and going back for the appropriate Murillo. Then, as they sought permission to hold him, FGR agents got a scolding from the judge for not coming “to the hearing prepared and not giving information clearly.”

But there was never much doubt that the hearing would result in Murillo’s incarceration, as did a second hearing days later. The decision was greased by Mexico’s “preventive detention” system, which you’ll be hearing more about soon as a movement to eliminate it gains steam. Preventive detention permits holding suspects before they are sentenced, or convicted, or tried, or even formally charged.

And said suspects can languish there for years. Just ask the controversial former Federal District interim mayor Rosario Robles, who was an ally of AMLO’s until she wasn’t. She spent three years behind bars without any solid accusations filed. As it turned out, she was finally released on the very day that Murillo was locked up. One out, one in.

As journalist Carlos Loret de Mola, something of a media star himself, put it, “How easy it is to put a rival in jail!”

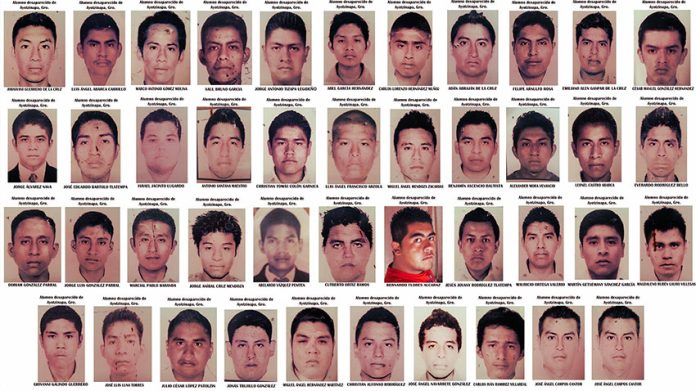

But this is no mere legal spat between Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and AMLO’s Morena. To grasp the enormity of the issue, you have to harken back to what it was like in the early fall of 2014 with the news that 43 young male students had vanished overnight. The anguish of the parents and the shock of the nation intensified as the PGR’s investigation seemed to stumble along haltingly, with no remains found save for three small body parts, and no satisfying explanation about how something like that could happen.

Less than two months after the event, Murillo issued the results of the investigation: The local police used force to detain the students. They then handed them over to the local criminal organization known as the Guerreros Unidos, who for reasons of their own killed them, burned their corpses, and tossed the bagged remains in the San Juan River. And that, Murillo emphasized, is the whole story. The term he used was “historical truth,” which has since become an ironic codeword for his version.

The cop-crime collusion is not disputed, though the fire-river part is. What’s really at stake, though, is Murillo’s assertion that the tragedy was a purely local affair. The victims’ families, along with the nationwide network of activists supporting them, would have none of that.

They knew that the students’ rural teachers college in the Guerrero locale of Ayotzinapa is a longtime hotbed of anti-government activism, spawning among others the 1970s revolutionary Lucio Cabañas, and thus ill-favored by the then-ruling PRI. It is that activism that led the students to commandeer buses in Iguala that day (unacceptable behavior, of course, but hardly grounds for an extrajudicial death sentence).

They also knew that the Mexican army has a strong presence in the area, that it was well aware of the cozy relationship between the Iguala police and the Guerreros Unidos, and that federal operatives are constantly monitoring all activity in Iguala and its surroundings. The massacre could not have taken place, they reasoned, without the federal government knowing about it.

Thus arose the battle cry “It was a crime of the state.” Murillo pooh-poohed the notion: “Iguala is not the Mexican state.”

And there things stood until the day before Murillo’s arrest, when the López Obrador administration released its own version of the events. AMLO’s man in charge of the investigation is Alejandro Encinas, a deputy minister of the interior who, like Robles and AMLO himself, is a former Mexico City mayor. Encinas is soft-spoken and articulate, with a seemingly gracious manner that may remind you of a favorite uncle who gives you a hundred-dollar bill on your birthday.

There was nothing avuncular about his explosive conclusions, though, or how he presented them at a press conference. What happened in Iguala, he said, “constituted a crime of the state.” With those words, he not only validated the activists’ contention by echoing their words, but also overturned eight years of the official position of the federal government. What’s more, he pointed the finger directly at the attorney general, calling his “historical truth” a fabrication intentionally designed to hide the role of the state in the crime.

The next day, Jesús Murillo was arrested and jailed. Scores of other arrest warrants were issued. How it will all turn out remains to be seen, but we do know one thing: Regarding the Ayotzinapa case, the federal authorities and the activists have come closer together.

Kelly Arthur Garrett has been writing from Mexico since 1992.