It is supposed to show that the United States is back in its own neighbourhood. Yet three weeks before its opening, the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles threatens to expose Washington’s weakness in the region.

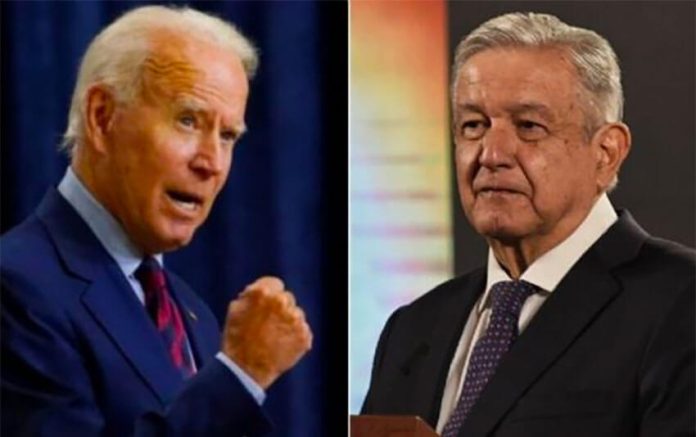

President López Obrador of Mexico, the United States’ most important ally in Latin America, has dropped a bombshell by vowing not to attend the triennial heads of government meeting unless the U.S. invites Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua — something the Biden administration had previously ruled out.

Caribbean nations backed López Obrador’s position, as did Bolivia. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro has still not decided whether to go and Argentina is wavering. Iván Duque, president of Latin America’s fourth-biggest economy, Colombia, could end up being the most important invitee.

“We’re in crisis mode now and it’s really embarrassing,” said Ryan Berg of the Americas Program at the Washington-based think tank CSIS.

“I cannot believe that we are three weeks out [from the summit] and we are where we are,” said Rebecca Bill Chavez, director of the Inter-American Dialogue think tank in Washington.

The U.S. has announced a partial relaxation of Trump-era restrictions on Cuba and dispatched a team to Mexico to bend López Obrador’s ear. But the struggle to persuade a key ally to attend what should be an indispensable meeting has already underlined America’s weakness.

China, by contrast, has been rapidly growing trade, investment and influence as it pursues Latin America’s abundant supplies of key commodities such as soy, copper and lithium.

Berg contrasted the troubled preparations for Los Angeles with a smoothly run Chinese virtual summit with Latin American and Caribbean foreign ministers in December, which agreed to a three-year action plan.

The row over summit attendance disguises a bigger problem: the lack of an ambitious agenda. Latin American officials complain that the Biden administration has not yet advanced anything comparable to the bold proposal for a Free Trade Area of the Americas floated by Bill Clinton in 1994, the last time the U.S. hosted the summit.

Beijing has been making diplomatic hay from the U.S.’s woes. The Chinese foreign ministry quickly supported Mexico’s argument that Los Angeles should not “be reduced to a ‘Summit of the United States of America’” adding: “Instead of benefiting Latin America . . . the U.S. has brought Latin America wanton exploitation, wilful sanctions, inflation, political interference, regime change, assassination of politicians and even armed aggression.”

China has already bought goodwill through US $130 billion of state bank loans to Latin America and the Caribbean over the past 15 years and $72 billion of corporate acquisitions over the past decade. Following a successful bout of vaccine diplomacy during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is now promoting its Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, which at least 20 Latin America and Caribbean nations have joined.

Washington has belatedly started to circulate proposals for the summit, which may include harnessing the financial firepower of institutions such as the Development Finance Corporation and the Inter-American Development Bank to help the region exploit nearshoring opportunities, said Cynthia Arnson, outgoing Latin America director at the Wilson Center in Washington. “If there is one way to rescue the summit it is to provide that kind of bold initiative.”

Whether even a successful meeting in Los Angeles can stem China’s inexorable advance in Latin America is questionable.

Among its trump cards, Beijing — unlike the Biden administration — prefers to talk business rather than criticize governments over democracy, human rights and corruption.

“The United States is rather like the Vatican,” said one top Latin American diplomat. “It’s very difficult to be accepted, you have to follow lots of rules, go to confession and you may still end up being damned, rather than going to paradise.

“The Chinese on the other hand are like the two well-dressed young men who knock on your door and ask you how you are feeling. They say they also believe in God and want to help. It’s the Mormon strategy.”

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.