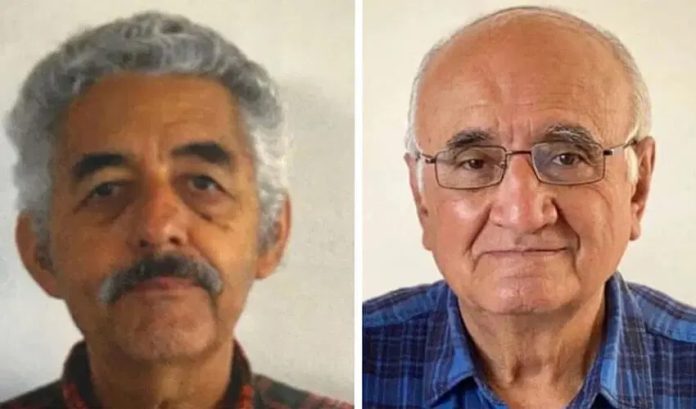

Dedicated to Javier Campos Morales, a.k.a El Gallo, and Joaquín César Mora Salazar, a.k.a. El Morita.

I visited Chihuahua’s Sierra Tarahumara for the first time some 15 years ago.

I arrived in Raramuri territory — this indigenous people’s name means “those with light feet” in their language — via El Chepe, one of only three passenger trains that today still exist in Mexico. I climbed onto that old choo-choo at 90 meters above sea level in the state of Sinaloa at the El Fuerte train station near the Gulf of California, gradually climbed in elevation until I found myself winding through the entrails of Copper Canyon and got off a few hours later in the state of Chihuahua at the El Divisadero train station at 2,238 meters above sea level.

The next morning, I was awakened at dawn by the aerial ballet of a dozen of zig-zagging hummingbirds in flight, their joyful 70 wingbeats per second impossible for the human eye to discern; they were right outside my window, overlooking a 2,000-meter-deep precipice. These are my favorite birds. I love their long-bent beaks, disproportionately long wings, and unending rush to get from one flower to the next. We call them “flower-licking birds” in the village where I was born.

Hummingbirds resemble multicolored butterflies, and from time to time — and without knocking — they sneak through the doorway of my studio/library in Mexico City. They study their own reflections in the glass of my large windows and then suddenly vanish across the terrace and back to the forest while I scribble away.

Late that night, looking through my window at the Mirador Hotel, on the edge of a colossal mountainous abyss, my mind could not shake the images of the three canyons one can see from there. Together with few other canyons, they comprise the Copper Canyon complex: the Urique Canyon (at more than 2,000 meters down, it’s Mexico’s deepest), the Tararecua Canyon and the Copper Canyon.

I recalled that many years back, an American friend, half-seriously and half-jokingly, told me that United States’ Grand Canyon had dreams to be like the Copper Canyon when it got older. “Canyon dreams,” I suppose you might call it.

Truth be told, the Grand Canyon has a long way to go; the Copper Canyon system is four times larger and almost twice as deep as the Grand Canyon.

Lying on the soft, white bedsheet without losing awareness of the shimmering moonlight crawling through my open window, I rested upon my belly a novel about the life of Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia — better known as Count Dracula.

The book’s black cover frames a red Transylvanian dragon with open jaws, from which a sinuous-arrowed tongue emerges. The thing is that, together with wrapping my head around the Big Bang and plate tectonics, vampires are my most irrational fears.

Here I am at one of planet Earth’s most mysterious, secluded and overwhelming natural areas — a portal of canyons through which one can be transported to parallel universes, even if only fleetingly. Meanwhile, the scent outside, the untamed Chihuahuan Desert and its bewildering biodiversity, lull the Raramuri land to sleep, and me as well.

But just over two months ago, on June 20, this idyllic version of the Sierra Tarahumara was suddenly ripped to pieces by a murder.

What happened that day revealed once again, to Mexico and to the world, the sad and brutal reality of day-to-day life in this region, the violence and anguish of a land that seems to belong to no one — much less to “those with light feet” who, for so many generations, have lived in extreme poverty and vulnerability in their mountain home.

I must confess that I have never cared all that much for priests — for a variety of reasons, but mostly because most of those I have met seemed fake, manipulative people who purport to sell, at all costs, a soulless version of Alice in Wonderland. But I always thought that Jesuits were a different breed of priest, that they were the ones who risk living — and dying — for what they believed in, the ones willing to fight for it.

One of the four or five times that I visited the Sierra Tarahumara, I was blessed to briefly meet Javier Ávila Aguirre, whose nickname was El Pato (the duck). He was a legendary Jesuit who since the 1970s has been fighting for Raramuri rights.

Not only did I like El Pato, he inspired me to do more for this forgotten land, though I now regret having done practically nothing.

Javier Campos Morales, a.k.a., El Gallo (the rooster) also made his appearance in this region in the 1970s, to be followed years later by Joaquín César Mora Salazar, known as El Morita (a diminutive of his last name). The two were also Jesuit missionaries — and they both were killed on June 20 at a church in Cerocahui, in the heart of Raramuri country.

When he was 16 years old, El Gallo joined the Jesuits and was ordained in 1972. He devoted the next half-century of his life to a pastoral mission in the Sierra Tarahumara — where he was nicknamed El Gallo because he could cock-a-doodle-doo like no one else. El Morita was 81 years old when he was murdered, having spent the last 23 years of his life in the Sierra, where he always dressed as a cowboy, in jeans and plaid shirts.

El Gallo and El Morita gave their lives for the Raramuri. They both were murdered while trying to help Pedro Eliodoro Palma, a tourist guide who, after being wounded, sought safe haven inside a chapel. He, too, was later murdered — in a series of events that could have been a scene taken from Gabriel García Márquez’s novel, Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

Both Jesuits were assassinated inside the Lord’s house, allegedly by José Noriel “El Chueco” Portillo Gil, a suspected local drug lord who then allegedly stole their bodies in an attempt to conceal the crime.

In the days after the murder, El Pato, the Jesuit I met all those years ago, told reporters that the two murdered priests had known El Chueco from childhood and that after killing them, El Chueco confessed his wrongdoing to another priest and begged for forgiveness.

Why were these two priests in the Sierra Tarahumara murdered? They were not simply killed by a sick, sad man. That is the easy answer.

They were also slaughtered by the insane violence, unpunished corruption and corrosive indifference that we all live among here in Mexico — which every day kills and disappears scores of women, young people, journalists, human rights activists, environmental defenders and many of my other compatriots.

Please take care of yourself, Pato.

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and the former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.