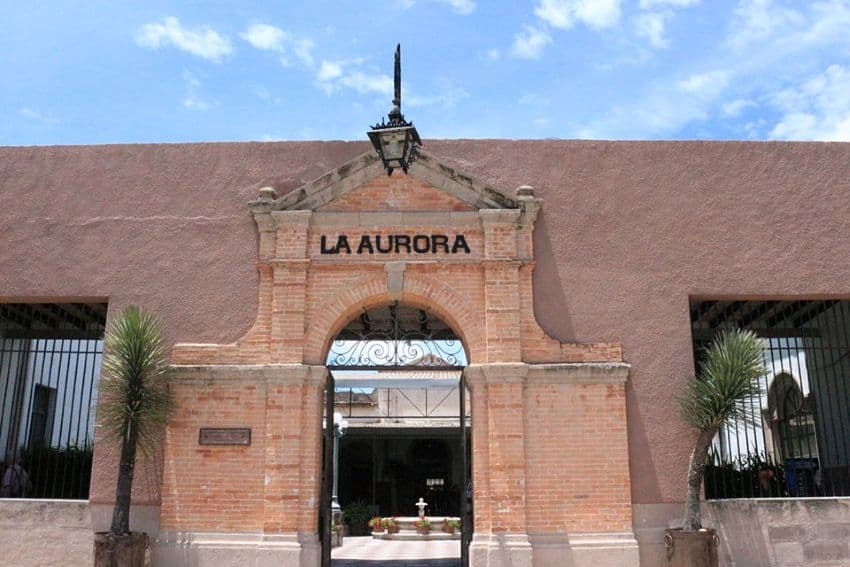

Back in the days before San Miguel de Allende became a world-class phenomenon (“The most beautiful small city in the world,” said Conde Nast), it was a sleepy little Mexican town where kids rode their bikes or played a rousing game of soccer in the middle of the streets. The city was then dominated, for 90 years, by a textile factory called La Aurora (now a dynamic art complex), which was the cornerstone of its economy, employing over 300 workers, all from San Miguel.

One of these men, José Cruz Gómez Corona, worked for the owner of La Aurora, Don Francisco Garay Sr., but he had different ambitions. In a glass shop that stood across from La Aurora, he learned to cut and etch and engrave glass, to bend and to shape it. He saw his newly acquired skill as the road to a better life, and in the back of one of the small houses built for Aurora’s workers, where he lived with his family, he made a studio. There, he invented a device that etched glass.

In the interim, local artisans were trying to sell small glass jewelry boxes to tourists, but with little luck. José saw something in that box and changed the look by adding a door and etching the glass — and voila! They sold!

Then along came a guy, Maya, from the U.S. He ordered boxes — first a few, then hundreds and then thousands — selling them to U.S. stores like Sears and Pier One, changing José’s life forever. His days of working for Don Francisco were over.

José taught his son Gustavo all he knew about glass, and when the boy was about 15, his uncle, Rafael, who worked for United Art Glass in Naperville, Illinois, asked if he’d like to come to the United States. He went.

The company’s owner, Joe Freeze, asked him to demonstrate his ability in glass work by making a lampshade, which Gustavo did. This led to a full-time job, and within a few months’ time, Gustavo, despite speaking very little English, was the workshop’s manager, and his uncle, his employee.

The company was known for its traditional leaded-glass windows, stained-glass repairs, and artistic workshops, catering to both hobbyists and professional artisans — and whenever Freeze had a job to install or to assess, he took Gustavo with him. Once he learned that Gustavo knew how to create shades in the Tiffany style, Gustavo’s horizons expanded, and so did his career.

Never leaving Freeze behind, Gustavo also worked part-time for other prestigious companies in the area, including Amity Stained Glass and the legendary Norman Bourdage, as well as Curran-Glass, which specialized in leaded-glass restoration, custom beveled glass and bent glass and the production of stained glass windows and light fixtures.

Bourdage crafted bespoke stained-glass windows, lamps and decorative panels for residential and commercial clients and also restored church windows, but it was at United Art Glass that Gustavo learned lead canes — the art of making slender, grooved bars of lead alloy that join individual pieces of glass into a unified panel. This technique, dating back to medieval times, remains the foundation of creating durable stained-glass artworks, particularly for architectural installations — and now Gustavo was a master!

In the early 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright had made his mark in Oak Park, Illinois, which was not far from Naperville, and so there was a lot of his glass to be restored. Wright had designed and built about 38 structures in the Oak Park area, and that’s where Gustavo and Curran-Glass came into play.

Gustavo had opened his own studio in 1991, in Wheaton, Illinois, aptly called, Wheaton Stained Glass. Buying an old Victorian home, perfectly suited to his trade, he worked on Frank Lloyd Wright restoration and repairs, along with Curran-Glass, while making his own objets d’art and teaching classes in stained-glass design.

But alas, all good things must come to an end. Gustavo was an undocumented immigrant, and although he bought property legally and paid his taxes, the IRS felt differently, and Gustavo was given a year to exit the U.S. There was no choice but to return to San Miguel. He had not cut ties there. He had commuted back and forth over the years and had a wife and two sons, whom he rarely saw. But it was time to go.

Coming back was not easy, but he figured if he could do it in the U.S., he could do it in San Miguel, and 25 years ago, this fantastic business was born.

Gustavo is an artist in stained glass, and glass of all kinds — from classic to modern, from windows and doors and to lighting and more. He worked and learned from top artists and architects in San Miguel along the way and became diverse in his knowledge of furniture and lighting, creating custom pieces for all facets of home décor. And these clients, knowing his talent and artistry — and his insatiable desire for perfection, happily gave him their trade.

Working with his two sons, Carlos and Christian, Gustavo hopes to take the business to a new level of design, and to expand into real estate, architecture and construction.

“We never saw COVID-19 coming,” he said, “so you can make plans, but you don’t know… It’s up to you to make it happen. When you fall down, you get up. When you fall down again, you get up again… It’s called persistence.”

Deborah McCoy is the one-time author of mainstream, bridal-reference books who has turned her attention to food, particularly sweets, desserts and fruits. She is the founder of CakeChatter™ on FaceBook and X (Twitter), and the author of four baking books for “Dough Punchers” via CakeChatter (available @amazon.com). She is also the president of The American Academy of Wedding Professionals™ (aa-wp.com).