You’ve probably heard the legend before. Somewhere around the year 1322, the people of the coastal settlement of Aztlán were ordered by their god Huitzilopochtli to leave home and wander westward until they came across an eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, devouring a snake. Where they found it, they would create the largest empire Mesoamerica had ever known. But how did Mexico City come to be built on a lake, and why is it so… not wet today?

Worn and weary, the tribe eventually stumbled upon the Valley of Mexico. Lo and behold, there it was! The eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, devouring a snake. Sitting atop a small island in the middle of a giant, shimmering lake. The lake was guarded by a string of mountains and volcanoes, including Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl. The pilgrims were thrilled. It only took 100 years.

The small island in the center of Lake Texcoco was situated close to another island in the same lake. The people settled here just as Huitzilopochtli had instructed, using dried mud, stone, and limestone plaster to build a vast kingdom made up of temples, marketplaces, schools, and homes. The two islands eventually fused to become Tenochtitlan, Mesoamerica’s most grand civilization, and the people became known as the Mexica (Aztec).

Grand Lake Texcoco, home of Tenochtitlán

The fact that Tenochtitlán thrived as a kingdom in the middle of a lake is extraordinary. Think of it like a bowl. Only the bowl is set in Mexico’s Central Highlands and is completely surrounded by mountains lacking any form of drainage. Each year would come an intense rainy season and this de facto “bowl” would fill with water, overflow, and flood the darn place.

But what Huitzilopochtli wants, Huitzilopochtli gets, and the Mexica were determined to find a solution. They decided to work with what nature had given them. Instead of fighting the lake (like the Spanish would eventually do), they used the abundance of water to their agricultural advantage, understanding that “floods were a precondition for a large part of the basin’s agricultural productivity,” according to the University of Texas at Austin.

So they began to build. The Mexica ingeniously constructed a system of canals, locks, and dikes to control water levels and prevent overflow. This divided salt water from fresh water, effectively creating two lakes. Where the water was brackish, a system of artificial land plots was created upon which maíz, beans, greens and onions could flourish. These small rectangular farms were known as chinampas, separated by canals through which canoes could transport newly harvested produce to the kingdom. Plots like this were probably not invented by Mexica but were enhanced in Tenochtitlan’s expansion.

Because the mountains contained abundant amounts of drinking water, a 16km aqueduct was designed to supply the citizens with hydration. Four major causeways were built linking Tenochtitlán to mainland Mexico for trade and economic stability. By the time the Spanish arrived 200 years later, Tenochtitlán’s 200,000 inhabitants made it one of the biggest and most vibrant cities in the world. It was awesome, in the true sense of the word, beguiling the conquistadors.

How do we know? Hernan Cortes said so. Yeah yeah, he was a bit of a boaster. Still, historians believe his opening description of Tenochtitlán in his second letter to the King of Spain is accurate:

“I am fully aware that the account will appear so wonderful as to be deemed scarcely worthy of credit; since even when we who have seen these things with our own eyes, are yet so amazed as to be unable to comprehend their reality.”

Unfortunately, the Spanish did not maintain it as such

The Spanish conquest initiated an almost-total disappearance of Lake Texcoco. Instead of working with nature like the Mexica had done so successfully for centuries, the colonists took up arms against it. Not because they wanted to save Tenochtitlan in all its glory, but rather because they wanted to create a European-style hub by turning the dikes and canals into squares and streets. Flooding would threaten the new city’s property value.

In 1607, a project known as Desagüe began. By constructing their own drainage system, the Spanish believed they could control the lake’s water levels. 40,000 local workers were rounded up and given hand tools to complete the dangerous job of excavating over 14 miles of channels and a 4 mile tunnel, 175 feet deep.

In 1629, a flood destroyed a significant percentage of the city, proving that the project had major flaws. Construction continued anyway through 1900. The city spread across the Valley of Mexico and usurped what was once a beautiful, bountiful environment for plants, animals, and people.

Lake Texcoco all but died

And now, we’re sitting on top of its grave. A waterless pit that was once a magical kingdom.

On the bright side, we get to enjoy one of the world’s greatest metropolises.

On the not so bright side, we don’t have enough water. Oh, the irony.

The failed construction of the Desagüe system has resulted in a lack of water. CDMX still sees heavy rains and occasional flooding, but the channels and tunnels are ineffective in collecting the overflow for reservoirs. The lack of penetrable surfaces block rainwater from filtering into cisterns underneath. Only about 8% of the flood water can be obtained, whilst the remaining 92% flows freely into polluted rivers and the city’s sewage system.

Leading to yet another grave consequence. The city is sinking. Lack of reservoirs and failure to implement a rainwater collection system have propelled officials to over-pump the underground aquifers for drinking water. The extraction process weakens the clay beds on which Mexico City sits. It drops 1 meter (3.2 feet) every year and that figure will increase as the population swells.

Want to see it with your own eyes? In CDMX’s Centro Historico, the buildings of the Zócalo and the surrounding area are noticeably crooked.

Moreover, draining Lake Texcoco significantly altered the environment. The region was once teeming with waterfowl, algae, fish, reptiles and insects. It bred reeds and water lilies, cooled the valley through evaporation, and contributed to cloud formation and precipitation. Lake Texcoco was vital in maintaining a balanced atmosphere.

However, there are plans to bring it back

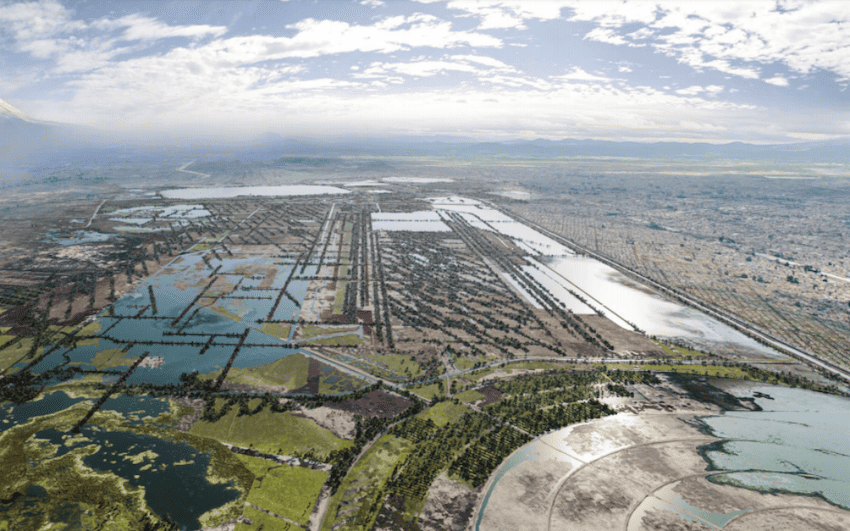

AMLO is overseeing the development of Lake Texcoco Ecological Park, a 14,000-hectare natural reserve on the site of the former Lake Texcoco on which sports fields, skateparks, restaurants, and a medical university will also be built. Its purpose is to preserve the flora and fauna that once flourished here through protected wetlands. It is scheduled to open later this year.

Want to see what Tenochtitlan looked like at its peak? Check out Thomas Kole’s incredible reconstruction of the brilliant Mesoamerican empire.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog, or follow her on Instagram.