The use of drones and lasers has allowed archaeologists to confirm the existence of two pre-Hispanic settlements buried beneath a third ancient city in the state of Michoacán.

José Luis Punzo, an archaeologist with the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), told the newspaper El Universal that Mexican and foreign archaeologists used drones and the laser surveying method known as lidar (light detection and ranging) to explore the site of the ancient city of Tingambato because much of it is covered with thick vegetation including avocado groves.

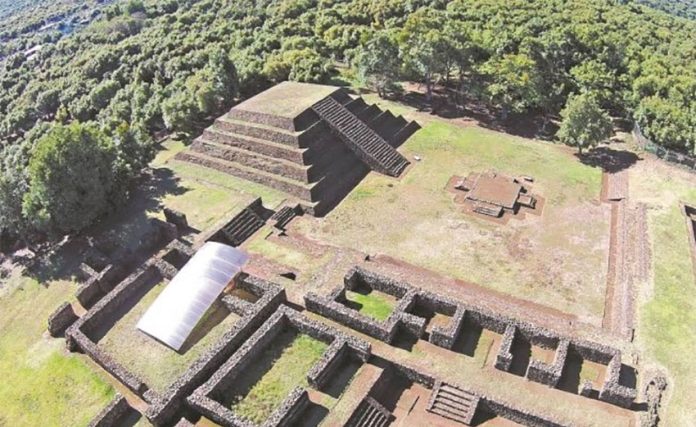

Located between the cities of Pátzcuaro and Uruapan, the Tingambato site was inhabited between the years 1 and 900, Punzo said.

“In the year zero [1 AD], there was a first village that was destroyed and another great platform was built on top of it. That remained until the year 500 AD,” he said. “It was also covered and another great city was built on top of it. That’s the one you can visit today.”

Punzo said that it is not known why the first two cities – now some four meters below ground – were destroyed.

The third city – abandoned in the latter half of the ninth century possibly because of a large fire or volcano eruption – shares some architectural features with the ancient city of Teotihuacán, located in modern day México state, suggesting that people from that settlement contributed to its construction.

It is also known as Tinganio, which in the Purépecha language means “place where the fire ends.”

Punzo said that using drones and lidar technology to explore the site was expensive but without them the work would have taken much longer.

“If we compared the results we obtained with them with the time … [the exploration] would have taken if we didn’t use them, we would realize that they are not so expensive,” he said.

Drones were used to take aerial photographs of the above-ground structures, the INAH archaeologists said, explaining that the images were used to develop 3D models of them. Punzo also said that drones helped to identify where excavations should take place to look for remnants of the buried cities.

Terrestrial and airborne lidar technology was used to map the site, he said.

“Terrestrial lidar … gives us extremely precise [information] about the buildings, the architectural relationships … at the site,” Punzo said. Aerial lidar, he added, enabled archaeologists to detect structures below vegetation.

“Then … the layer of vegetation is removed. In other words, cities are discovered with this [airborne lidar technology], Punzo said.”

In addition to the INAH team, archaeologists from the National Autonomous University, the University of Auckland in New Zealand and the University of Strasbourg in France worked on the exploration project.

As part of their studies, the archaeologists were able to determine that the remains found in a grave at the site in 2012 were those of a young woman aged between 15 and 19. The woman was buried in pre-Hispanic times along with some 19,000 precious stones, sea shells and human bones.

“We’re working with Harvard University to carry out DNA studies. We’ve discovered that she had a deformed skull and her teeth were modified; in other words, she was a high-ranking person,” Punzo said.

The archaeologist also said that INAH is planning another study using drones and lidar technology at the Tzintzuntzan pre-Hispanic site, also located in Michoacán.

“It’s a lidar research project in conjunction with the National Council of Science and Technology but everything is on hold because of the Covid-19 health crisis.”

Source: El Universal (sp)