Joselino Álvarez wanted to keep the young chalum trees he had planted on his half-hectare parcel of land in the Lacondona jungle in Chiapas. But the employees of the federal government’s Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life) tree-planting program had other ideas.

“They said no, that it has to start from zero, that there can’t be any plants,” Álvarez said. “I showed [the chalum trees] to the engineer, but they did not allow me to keep them.”

Álvarez, a native Mayan speaker from the La Cañada ejido (land ownership cooperative), an hour from the Guatemalan border, knew from decades of experience that the 12-meter chalum trees were perfect for protecting smaller coffee and cacao plants from the harsh tropical sun. But he could not argue with bureaucracy. The money from the program would make a big difference for his family.

Álvarez’s story, told by Nadia Sanders in the magazine Gatopardo, highlights a key problem with the Sembrando Vida campaign, one of the current administration’s most important social programs: due to the lack of planning and organization issues, the initiative’s core goal of reforestation is not being accomplished. In fact, the requirement that only unforested plots of land qualify for the program appears to have contributed to deforestation.

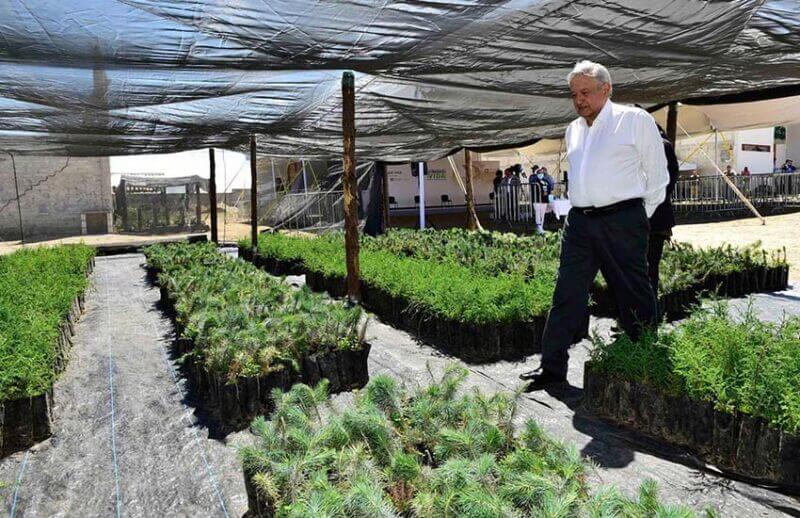

Through Sembrando Vida, which began in 2019, farmers are paid 5,000 pesos a month to cultivate timber and certain crops on small parcels of previously bare land. The money is significant for many campesinos, much more than some make selling their produce.

As a result, there is a strong incentive to clear land in order to qualify for the program. And some participants, like Álvarez, report being told by Sembrando Vida employees to clear their land if they wanted to receive money.

The program received 15 billion pesos (US $750 million) in funding in 2019 to set up an operational structure with 3,000 employees that would enroll and train 230,000 farmers. Each farmer would be responsible for a 2.5-hectare plot of land. Farmers would provide the land.

The rollout was fast, set to a political timeframe rather than an agricultural one, Sanders wrote. Some farmers were even required to plant crops in the dry season, when they were sure to die, because of government-mandated goals for progress.

Other requirements presented similar mismatches with the reality on the ground: few farmers could scrape together 2.5 hectares of open land. So the decision was made to allow groups of people to join under one name.

Many, like Álvarez, used this route to enroll. His group has 2.5 hectares between all of them and shares the program’s payments depending on the size of each person’s parcel.

This small administrative change created a huge logistical challenge for Sembrando Vida employees, who operate in two-person teams assisted by 12 interns from the Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro (Youth Building the Future) job training program. Each team is responsible for inspecting 100 of the 2.5-hectare parcels every month to make sure that they are, in fact, planting trees and cultivating crops.

But with each parcel split into many smaller parcels and dispersed through extremely remote communities, the amount of work to complete the inspections increased exponentially. Employees also were not well prepared for the challenges they faced.

They received minimal training, and some entered their positions without prior experience in reforestation or agricultural production. The regional coordinator for Palenque, Chiapas — a well-paid position — previously taught communications to high school students. The coordinator for the La Huasteca region was formerly a hotel manager with a background in tourism studies. The regional coordinator for San Luis Potosí was a former member of Servants of the Nation, a group to enroll new members in government social programs. She was also a Morena party legislative candidate.

“They sent them to war without weapons … they did not receive any training. They came from another state, recently graduated from university,” one person interviewed by Gatopardo commented.

Charges of deforestation stem from anecdotal accounts by forest rangers and reports of illegal logging that streamed in after the project began operations in Mexico’s southeast. These claims are backed up by a World Resources Institute report, which says Sembrando Vida may have accidentally caused the deforestation of 73,000 hectares of land just in 2019, its first year of operation.

David Hernández, a farmer from the Agua Perla ejido near the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve who also enrolled in Sembrando Vida, is happy with the sizable increase in income it provided. Understanding that it would likely end when President López Obrador left office, Hernández invested in rambutan trees, whose fruit fetches a decent market price, so that he could continue providing for his family after the program shuts down.

It was not Hernández’s first time engaging with a government program. He recalled when members of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor program, led by the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (Conabio), came to his community to teach residents about environmental conservation and soil regeneration.

He said the Conabio program was a turning point for resource conservation in Agua Perla.

“We really see the difference from how it was before. We were using up almost everything,” Hernández said. “We had many animals and were eroding the mountains. We were losing birds; even the macaws left. [That program] has helped us maintain the natural springs. We are rich because we have one that still flows.”

But Conabio is one of many government environmental departments that have faced steep budget cuts in recent years, and the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor program ended in 2018. Meanwhile, the current administration has proposed expanding Sembrando Vida to Central America as a means to create jobs and decrease illegal immigration.

Back in La Cañada, Álvarez continued to care for his plants to the best of his ability, though the conditions were not ideal. He had 475 plants through the program: pineapples, cedar and cacao trees. But the cacao, without shade, grew slowly and did not thrive.

“If the engineer had let me … the cacao trees would now be this tall, greener and prettier,” Álvarez told Gatopardo, indicating above his head. “But we had to comply with their rules of operation.”

With reports from Gatopardo