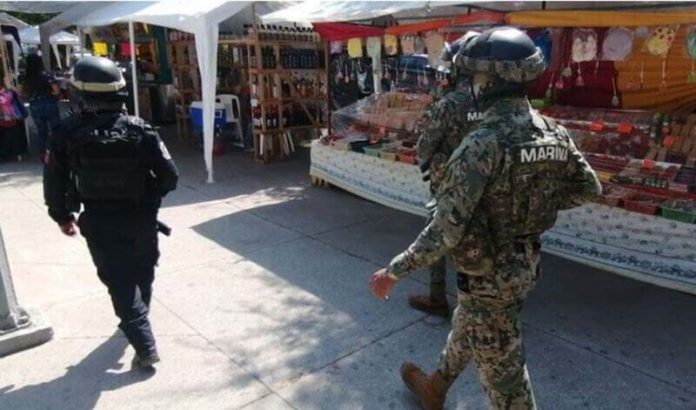

Army and navy personnel now head up security ministries in 10 of Mexico’s 32 states, triggering concern about the increasing militarization of the country.

The governors of seven of 11 states won by Mexico’s ruling Morena party at the June 6 elections have appointed military leaders as their security ministers.

State police forces in Baja California, Baja California Sur, Colima, Guerrero and Tlaxcala are now under the control of ministers who serve in the navy, while those in Michoacán and Sinaloa are led by army personnel.

San Luis Potosí Governor Ricardo Gallardo, who took office for the Ecological Green Party in September, also appointed a soldier as his security minister, while Morelos and Tamaulipas, led by Social Encounter Party and National Action Party governors, respectively, already had security ministers from the navy before the recent elections.

The new Morena governors’ appointment of military personnel to security minister roles is in line with President López Obrador’s desire to have soldiers and marines in positions of power.

On October 19, the president publicly advised new governors to speak to the ministers of national defense and the navy before making security minister appointments.

“… I recommend that you consult with both Admiral [Rafael] Ojeda, the navy minister, and [army chief] General [Cresencio] Sandoval so that you have honest, upright people,” López Obrador said.

He implied that the navy and defense ministers could recommend “incorruptible” people to take on the security roles so that “what was very common before — that [organized] crime was in control of police forces in the states and municipalities — is avoided.”

Carlos Mendoza, a public security expert and academic at the National Autonomous University, condemned the practice, asserting that it shouldn’t occur because security ministries are civilian bodies. The appointments are indicative of the creeping involvement of the military in public life, he said.

López Obrador has relied on the armed forces for a range of nontraditional tasks, including public security, infrastructure construction and vaccine distribution.

“There’s not even an argument now that [the appointments] are going to be temporary and that civilian control [of the security ministries] will return,” Mendoza told the newspaper Reforma.

“… There is an explicit narrative of extending military control of police forces, and I think that’s something that is very worrying,” he said.

Mendoza charged that López Obrador’s October 19 remarks amounted to a clear directive to the new Morena governors rather than a presidential suggestion.

“It’s very concerning that the [federal] government sends these messages, because the army is occupying more positions of importance,” he said.

Mendoza claimed that governors have appointed military personnel as their security ministers because by doing so they can avoid direct responsibility for combatting insecurity. Alejandro Hope, a security analyst, contended in an opinion piece published Monday that something similar is occurring in Sonora, but the northern state’s governor — former federal security minister Alfonso Durazo — is outsourcing responsibility to the National Guard rather than the military.

“Given the problem of violence and insecurity in certain places, they [governors] prefer to allow the army to take responsibility for the failure or success [in combatting crime],” Mendoza said.

“I believe that [it creates] a space of comfort and convenience [for governors], and it’s obviously very conformist,” Mendoza said, referring to their compliance with the president’s wishes.

Mexico United Against Crime (MUCD), a civil society organization, also raised concerns about growing militarization in two recent reports.

“It’s a fact that public security in Mexico has been gradually militarized until reaching what appears to be a point of no return,” MUCD director Lisa Sánchez wrote in one report.

“Over four decades, and more precisely in [the most recent] two, the country went from entrusting the manual eradication of illicit crops to the military to placing the management of anti-drugs operations; the fight against organized crime; the re-establishment of order in municipalities, states and territories; and crime prevention into their hands,” she wrote.

MUCD said in another report that “the growing militarization of public security has been presented by civilian governments … as a necessary evil to return security to our country.”

But “this strategy has not been capable of improving security conditions and peace in Mexico,” the organization said.

Former president Felipe Calderón significantly ramped up the use of the military to fight organized crime, deploying the armed forces to combat Mexico’s notoriously violent cartels shortly after he took office in late 2006. Mexico’s homicide rate has steadily increased since then, reaching its highest ever level in 2019 before falling slightly in 2020. The military has been accused of a range of crimes, including arbitrary detentions, torture and extrajudicial killings.

The practice of putting military leaders in charge of civilian security ministries intensified during the Calderón years and continued during the 2012–2018 administration led by former president Enrique Peña Nieto, who also used the armed forces to combat violent crime.

Despite pledging to gradually withdraw the military from the nation’s streets before he took office, López Obrador published a decree in May last year that ordered the armed forces to continue carrying out public security tasks for another four years, an about-face that appeared to acknowledge that the National Guard had failed in its mission to reduce violence.

His use of the military, however, comes with a significant caveat: don’t use force against criminals unless it’s absolutely necessary.

The president’s instruction — part of his so-called abrazos, no balazos (hugs, not bullets) security strategy — has been criticized for giving cartels free rein to carry out their criminal activities. Hope, the security analyst, told the Associated Press last week that the federal government’s strategy in Michoacán is clearly “some sort of pact of non-aggression.”

“… [The soldiers] are not there to disarm the two sides [the Jalisco New Generation Cartel and the Cárteles Unidos] but rather to prevent the conflict from spreading,” he said.

With reports from Reforma