At the southern end of Tlaxcala lies the ruins of a city you may not be familiar with — Cacaxtla, which exerted military and economic control over much, if not most, of the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley and regions as far away as the Gulf Coast and the Mexican basin.

That is, until the Popocatépetl volcano erupted in A.D. 1000 and it was abandoned.

Actually, its decline, according to historians, began about 100 years earlier. But during its peak, between A.D. 650 and A.D. 900, it was a powerful city, united for about 300 years with another city a short distance away by the name of Xochitécatl.

All that can be seen of Cacaxtla today is a large pyramid called El Gran Basamento (Great Platform) and some surrounding smaller pyramids. Elites and priests — almost certainly all men — ruled over and had exclusive use of Cacaxtla. Women were the ones who held fertility rituals at Xochitécatl, rituals in which everyone could take part.

Like Cacaxtla, Xochitécatl was abandoned when Popocatépetl erupted in A.D. 1000.

Although Cacaxtla had been described by Diego Muñoz Camargo, a 16th-century historian, it nevertheless remained unknown in modern times until it was accidentally rediscovered by maintenance workers in 1975. Shortly afterward, archeologists began excavating the site for the next six years.

Cacaxtla, the capital city in an area occupied by a group known as the Olmeca-Xicalancas, was first settled 2,500 years ago, although it’s not clear who the first inhabitants were. Its name means “Place of the Cacaxtles,” which were boxes that were used to carry a variety of products.

The city’s rise as a regional power came after the fall of the ancient city of Cholula in Puebla sometime between A.D. 650 and A.D. 750 and the collapse of the city of Teotihuacán around 750 A.D.

El Gran Basamento, the only building on the site that can be entered, contained the main religious and civic buildings, along with buildings that housed the priests and ruling class. Under one of the courtyards of the Palacio (Palace), where the ruling class lived, remains of two hundred sacrificed children were found.

The building is now covered with a huge roof to protect the brilliantly colored murals, which were done in a style typical of Mayan paintings and murals.

On opposite sides of an entrance to one large room are the murals known as Hombre Ave (Bird Man) and Hombre Felino (Feline Man), both probably depicting the city’s priests or rulers.

Hombre Ave is a painting of a man dressed in elaborate feathers. Surrounding the figure are drawings of marine animals and he stands atop a plumed serpent. Hombre Ave and the plumed serpent are all depictions of Quetzalcoatl, one of the most powerful gods in the Mesoamerican pantheon. This god was revered throughout Central Mexico and as far south as Guatemala. Among other things, he was worshipped as the creator of humans and the world.

Hombre Felino holds the skin of a jaguar in one hand, from which drops of blood fall; these were drawn to mimic raindrops falling. The figure of Hombre Felino is associated with rain. Because of that and some other drawings alongside the figure, it’s believed that this mural was made to honor Tláloc, the god of rain. Tláloc is often associated with Quetzalcoatl.

It’s believed that these figures served to demonstrate or reinforce the power the priests and rulers held over the city. Other murals are found in the structure known as Templo de Venus (Venus Temple) and the Templo Rojo (Red Temple).

The mural in the Templo Rojo lines a staircase. There’s a figure of a man known as the Comerciante (Merchant or Trader) who’s carrying a cacaxtli (a basket) on his back. Surrounding him are corn, cocoa beans and marine animals, which may have been items that were traded.

The most impressive mural is the Mural de la Batalla (The Battle Mural). It’s almost 26 meters (80 feet) long and shows a battle between two ethnic groups. The defeated group, whose soldiers have deformed heads, has been identified as Maya. This mural is behind Plexiglas and, because of its exposure to the sun, is more faded than the other murals. Interestingly, the buildings in which this mural, as well as Hombre Ave and Hombre Felino, were housed were partially demolished at some point to make room for new buildings. The murals were covered, which helped to preserve them.

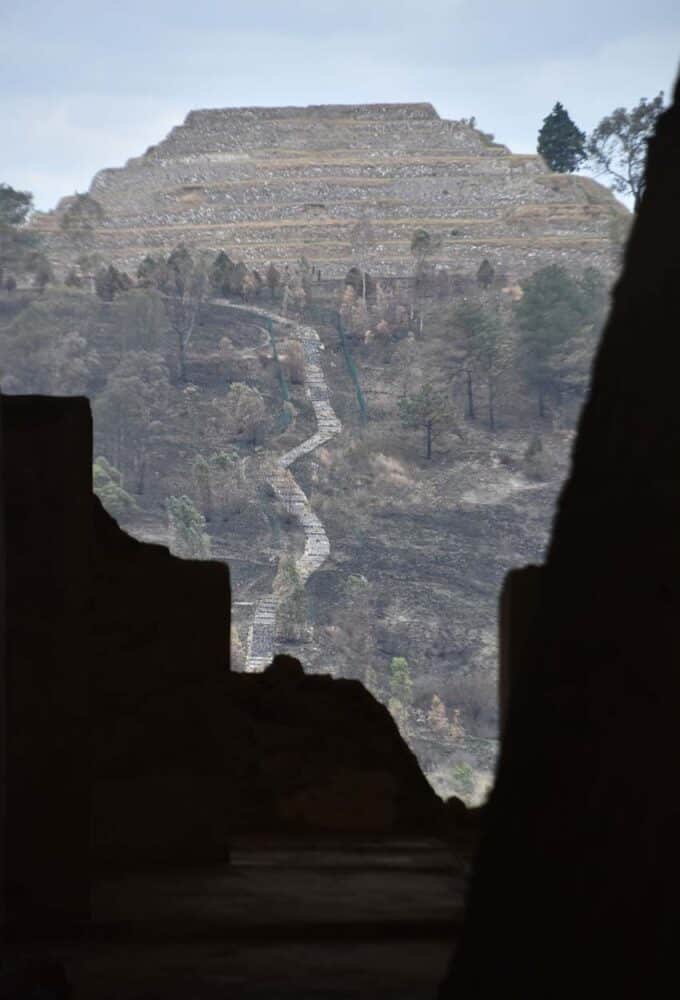

A path links Cacaxtla to Xochitécatl.

Xochitécatl, whose name translates to “Place of the Lineage of Flowers,” was first occupied almost 3,000 years ago. It sits on top of an extinct volcano and it’s believed that the site was chosen because it’s surrounded by Popocatépetl and La Malinche, both active volcanoes, and Iztacchihuátl, an extinct one. Indigenous groups worshipped volcanoes as gods.

Xochitécatl was abandoned in A.D. 200 after Popocatépetl erupted and then reoccupied about 500 years later, when it united with Cacaxtla.

It was here, in Xochitécatl, that women performed fertility rites. These rites included sacrifices and the remains of sacrificed women have been found throughout the site.

Today, four structures may be seen: the Piramide de las Flores (Pyramid of the Flowers), Edificio de la Espiral (Spiral Building), Edificio de la Serpiente (Serpent Building) and Basamento de los Volcanoes (Platform of the Volcanoes).

Piramide de las Flores is the largest building in Xochitécatl, standing 37 meters (about 122 feet) tall. Stone columns, part of a portico, are all that remain of the temple that once stood on top of the pyramid. Through these columns, La Malinche can be seen in the distance. The remains of female sacrificial victims have been excavated under the stairs leading up the pyramid.

Across from Piramide de las Flores is Edificio de la Espiral, which was built when the site was first settled. It’s believed to represent Popocatépetl. Residents of nearby San Rafael Tenanyecac still hold ceremonies on top of this building, placing a wooden cross on top.

Fertility was associated with water, and there are several structures called monolith fonts at Xochitécatl that may have been used for fertility rituals and also to collect water. One of them, a huge bowl-shaped object, sits in front of the Edificio de la Serpiente, the oldest building on the site; its construction started 2,500 years ago. It’s been hypothesized that women may have bathed in these structures during rituals.

Basamento de los Volacanoes was built between 600 and 900 AD, when Xochitécatl and Cacaxtla were at their peak. The low walls of the platform slope and their stones were precisely cut to fit tightly together.

Hundreds of small female figures, some depicting a pregnant woman, some with a woman holding a baby, have been found at the site and can be seen in the museum located there.

My first attempt to visit Cacaxtla and Xochitécatl was thwarted when I was told that visitors had to provide proof of being vaccinated for Covid. No such proof was required on the second trip but it might not be a bad idea to call to make sure. Phone numbers: 246 462 9375 and 246 462 9031.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.