At the Txori Ornithological Foundation, a nonprofit NGO just 20 kilometers northwest of Guadalajara, there’s generally a lot of squawking going on.

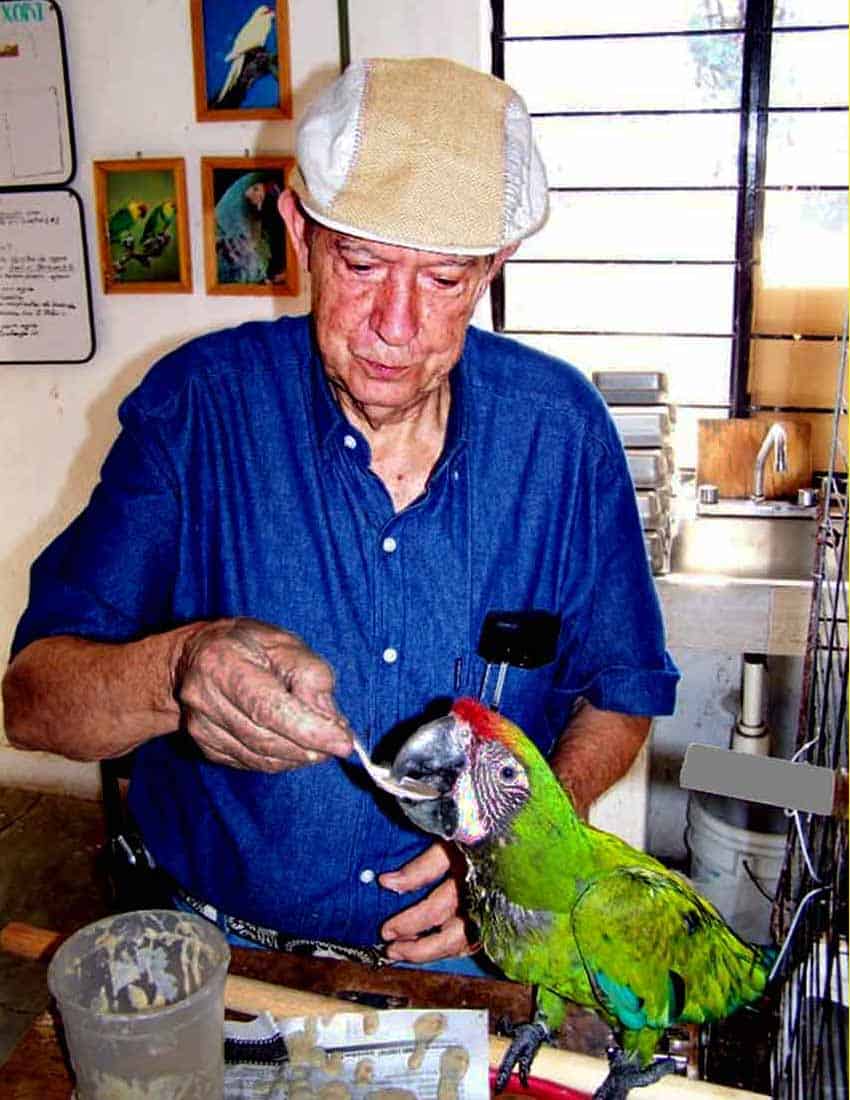

“Here we breed Mexican macaws, parrots and parakeets,” Txori Director Victor Busteros told me, “and we also rehabilitate rescued birds, all with the aim of reintroducing them back into the wild.”

That dream is finally coming to fruition soon: Txori plans to do its first release of military macaws.

Txori (pronounced “Chori”) is Basque for “bird.” Victor’s father, Cándido Busteros, who started the organization, also gave the organization its name. He was a Spaniard who fled his home country to France during the Spanish Civil War.

“Then the Nazis took control of France, and he escaped to Mexico,” says Victor.

While Cándido Busteros lived in Mexico City upon his arrival here, he eventually took a horseback tour from Guadalajara through the Sierra Occidental.

“He was utterly amazed at the beauty of those mountains, woods and jungles, but what fascinated him most were the parrots, in particular the guacamayas, which were plentiful in those days,” says Victor.

Cándido returned to Mexico City but never forgot those guacamayas. When he moved to Guadalajara in the 1970s, the first thing he wanted to do was to repeat his ride to Tomatlán.

“Unfortunately,” says Victor, “in those days the government was hell-bent on ‘development,’ convincing the campesinos to burn the woods and plant corn. So, the great flocks of parrots and macaws were all gone.”

As a result, Candido Busteros started a small bird rescue center in his home. It may have been the first Animal Rescue Center of any kind in Guadalajara, but it was exclusively for parrots. In the 1990s, the center, now named Txori, was given legal status.

It was at this point that Busteros decided not only to rescue sick or unwanted birds but also to start raising macaws with the idea of eventually returning them to the wild in places where their populations had dropped drastically.

“Some university ‘experts’ said my father was crazy,” says Victor Busteros, “and that a macaw raised in captivity would never stand a chance in the wild, but my father began to distance himself from these people and started working with ornithologists in Costa Rica and Honduras who were already doing exactly what he had in mind.”

These ornithologists were liberating macaws left and right — even scarlet macaws raised right here in Mexico at the Xcaret resort in Playa del Carmen. People were saying that the birds were surely going to die.

“Instead they survived. It’s been documented!” Victor says. “And, finally, the ‘experts’ in Mexico began to change their minds. So, based on these results, we’re working on our plan for releasing green macaws (Ara militaris) for the first time, and for this species, we will be the pioneers.”

Txori presently has 20 habitation units, 10 of which are for breeding pairs. They also have a bird hospital, incubators, hatchers, a maternity ward with closed-circuit TV, a warehouse, gray-water treatment plant, solar cells, a garden and quarters for the caretakers, some of whom are volunteers.

“Among our other guests, we have 20 green military macaws here,” says Victor. “We have three reproducing couples and, of the 20, nine are ready for release.”

“We feed all our birds a well-balanced diet; we create activities for them and we care for their mental health as well. If parrots are mentally and physically in good shape, it means whoever is raising them is doing a great job,” he said.

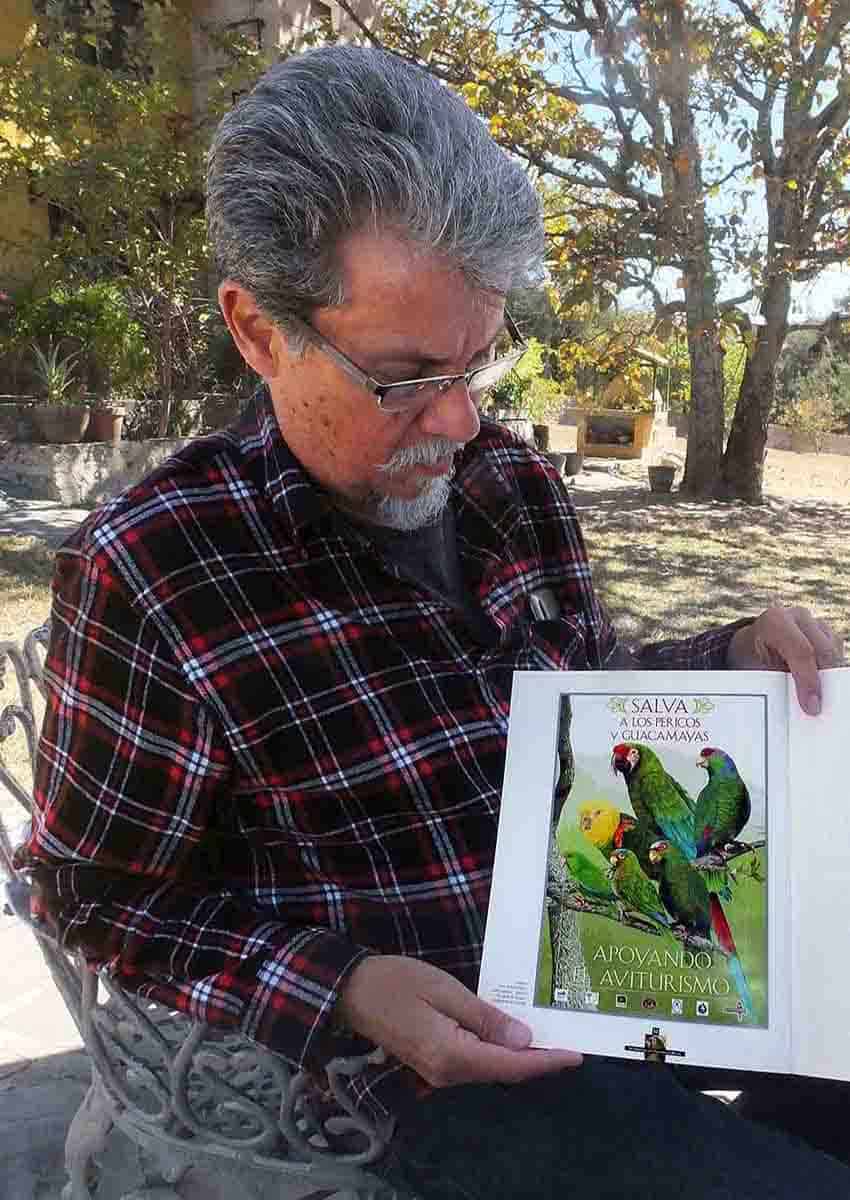

Txori plans to do its first release of military macaws at Rancho el Mexicano, located north of Guadalajara at the top of the 500-meter-high Santiago River Canyon. The area already has a healthy population of macaws.

It is hoped that the site will become a popular spot for parrot-watching tourism. Two monitoring points will also be set up for parrot-watching and to keep tabs on the released birds.

“Local people are very involved in the project,” says Victor, “and will benefit from it economically.”

Txori ran into serious problems when COVID-19 struck. Its financing came from a trust, which, in turn, depended on the earnings of two businesses in Guadalajara.

“Because of the pandemic,” says Busteros, “one of the businesses was shut down and the other was severely impacted. So there was suddenly no money, and we were on our own, trying to figure out how to survive.”

Curiously, the aviary was saved by an owl that also happens to be a robin — an English man with whom Victor once worked in Greenpeace and who now lives in France.

The Englishman is Robin Perkins, a musician whose professional name is El Búho (The Owl). El Búho specializes in electronic music that incorporates the rhythms, traditions and melodies of Latin American folk music and the the organic sound of waterfalls, bird songs and crackling leaves.

“The result,” says his webpage, “is a dreamy, deep, melodic journey that entrances as much through headphones as it does on the dance floor.”

Under the label Shika Shika, Perkins created “A Guide to the Birdsong of Mexico, Central America & the Caribbean.” an album of electronic music incorporating the songs of endangered birds.

The sample track linked above features the song of Mexico’s black catbird. You can listen to the entire album on Spotify.

“I have always firmly believed in the power of art and music as a tool for change, to deliver a message and raise awareness,” says Perkins. “My hope is that this project can go some way towards supporting those [organizations] doing an incredible job in preserving birds, their habitats and their songs for the generations to come.”

Thanks to El Búho’s help, one of those organizations, Txori, is alive and well and working hard to save some of Mexico’s most lovable endangered birds.

- If you’d like to see Txori’s work in person, they welcome visitors, but you must contact them in advance at info@txori.org.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.