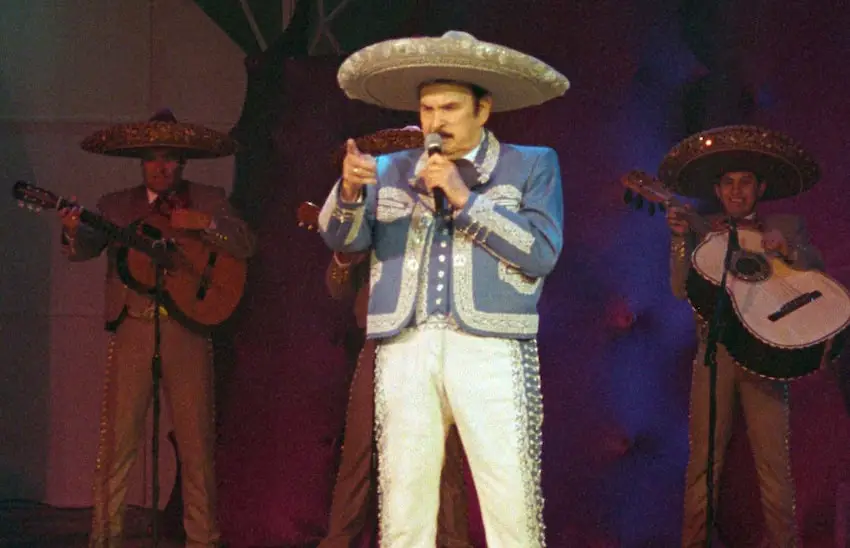

Unless you’re living under a giant rock, you’ve heard a classic corrido. You know — the soulful Mexican ballads that gradually take over the barbeque when a little too much tequila has been poured. The karaoke tune of choice for after work happy hours at the local cantina. The melody that guides the traditional father-daughter dance at your neighbor’s quinceñera.

The most generalized definition we can muster is that a corrido is a narrative ballad. Not very specific, as Whitney Houston and Taylor Swift are also both categorized as ballad singers, but it’s a start. A Mexican corrido is something different. It’s something very particular. A Mexican corrido is an eloquent form of story-telling, an oral history told from the perspective of the rural and working classes.

A brief history of corridos

Corrido music emerged on the US-Mexico border in the late 1800s and exploded during the Mexican Revolution. It served as a form of media for the general public — lyrics detailed the exploits of outlaws, battles lost and won, the lives of revolutionaries, even love and heartbreak.

Some highlighted a specific person — César Chávez in “Corrido de César Chávez”, composed by Lalo Guerrero in 1968. Others pertained to particular events — like the death of Pancho Villa of which there are dozens. Other sing the plights of romance, like “El Rey de Corazones” by Ariel Camacho y Los Plebes Del Rancho.

The traditional structure of a corrido

Corridos initially followed a very specific structure that consisted of the following actions:

- The singer greets the audience.

- Introduces location, time, and the main character.

- Explains the character’s role in the story.

- Explains the story.

- Bids farewell to the main character.

- Bids farewell to the audience.

While the formal structure has not stood the test of time, corridos are still used today as a means of expression modernized through narcocorrido music. Maybe a more accurate moniker would be ‘corrido tumbado’, a blend of Mexican regional melodies (think Ranchera, Norteño, Mariachi) with trap and hip hop. If you like hip hop beats and you like trumpets, the mix might sound appealing.

The lyrics stay somewhat true to the basic elements of corrido — stories told from an underserved, often impoverished class of society. The themes have drifted from that of border conflicts and broken hearts to the realities of living within the confines of Mexico’s drug war. Rebels are still glorified, though songs focus less on the likes of Pancho Villa and more on individuals like El Chapo.

Who is Peso Pluma?

And that’s where Peso Pluma enters the scene.

The 24-year-old Mexican star and Billboard Latin Music Awards’ Artist of the Year was born in Jalisco and is regularly embroiled in controversy. He keeps his personal life under wraps, but on stage he’s unreserved. The artist has been accused of openly inhaling drugs during a performance in Argentina. He smashed a TV monitor and threw it off stage in Ecuador. He canceled a concert in Tijuana after receiving death threats from Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación.

Peso Pluma has been denounced by AMLO and Juan Antonio Coloma, president of the Chilean Senate. Leaders point to his “normalizing narcoculture” in songs like “Gavilán II” and “PRC” in which he references drugs, sex and murder with laudable undertones. Or perhaps, overtones. In “Siempre Pendientes” he goes so far as to praise El Chapo, founder of the Sinaloa cartel. Some suggest this is hinting at a possible relationship with the notorious syndicate.

For this and other reasons, Chilean officials tried to ban him from this year’s Viña del Mar festival to no avail, with Coloma stating that Pluma’s participation would result in “a normalization of narcoculture in our country and it is unacceptable.”

Not everyone believes his music to be threatening. Besides arguments citing freedom of speech and the need to appeal to a younger audience, many supporters believe that narcocorridos unveil government neglect and violence spurred by former President Felipe Calderón’s “war on drugs” initiated in 2006. There are varying reports of the catastrophic results of the campaign, with related death counts ranging from 40,000 to more than 400,000. Some have claimed these statistics are largely ignored by those in power and music is the best way to tell the tale.

What’s the fuss?

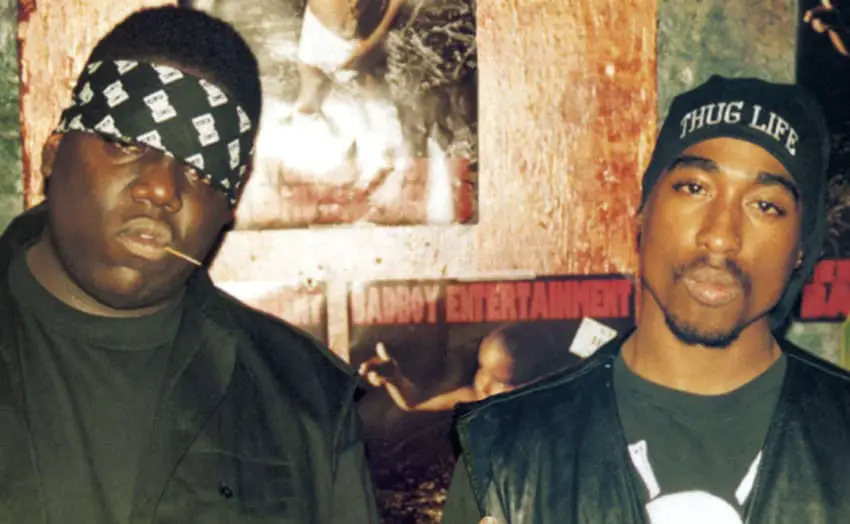

From the point of view of this American writer, nothing Peso Pluma, Los Tigres del Norte, and Movimiento Alterado sing about seems any different from the rap songs I’ve been listening to since the early 90’s. This begs the bigger and more obvious question of the repercussions of celebrating such lifestyles through music, but that is a debate for which I am not informationally equipped.

As a thorough writer should, I engaged in multiple avenues of research while crafting this article. Naturally, this included listening to Peso Pluma and the other artists mentioned above. Only a handful of Peso Pluma’s songs struck me as distinctly Mexican. That said, I did find myself jamming to Movimiento Alterado’s heavy use of traditional regional instruments. I can say with confidence that despite the lyrics, I have no desire to buy drugs (though another pan dulce would be nice and as far as I can tell, sugar is the worst drug out there) or objectify the women surrounding me in this cafe.

But I’m an adult. Therein lies the difference.

If you are a Peso Pluma aficionado, he will be kicking off his North America “Exodo Tour” in Chicago on May 25, 2024. Tickets start at US$35 and are available on Ticketmaster.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog, or follow her on Instagram.