If you’ve ever met a Mexican and wondered why their name is twice as long as yours, you’re not alone. At first glance, having two last names might seem like an unnecessary complication, an administrative headache or an elaborate memory test. However, in Mexico (and other Spanish-speaking countries), this tradition is more than just a naming convention; it’s a reflection of identity, heritage, and family pride, ensuring that both paternal and maternal lineage are acknowledged and preserved.

Unlike in English, where a last name is singular, in Spanish, we use the term apellido, and we have two. This system allows for precise identification and strengthens the connection to both sides of a person’s ancestry. The formula is simple: first name + father’s first apellido + mother’s first apellido. For example, if Luis Pérez Ramírez and María García López have a child named Juan, his full name will be Juan Pérez García, carrying both his paternal and maternal surnames forward.

Another key aspect of this naming tradition is that women do not lose their birth names after marriage. Unlike in many English-speaking countries, where a woman traditionally takes her husband’s surname, in Mexico, a woman keeps both of her original last names. Some may choose to adopt their husband’s paternal surname, connected by the preposition “de” (meaning “of”), as a social custom rather than a legal requirement.

A blissful tradition that originated in dark times

This tradition has its roots in Spain and dates back several centuries. Before this system, people were recorded by their given name and their parents’ names. Parish records, which were the primary method of documentation before civil registries existed, often listed individuals in a straightforward way, such as “Antonio, son of Francisco and Laura,” without any formal surnames.

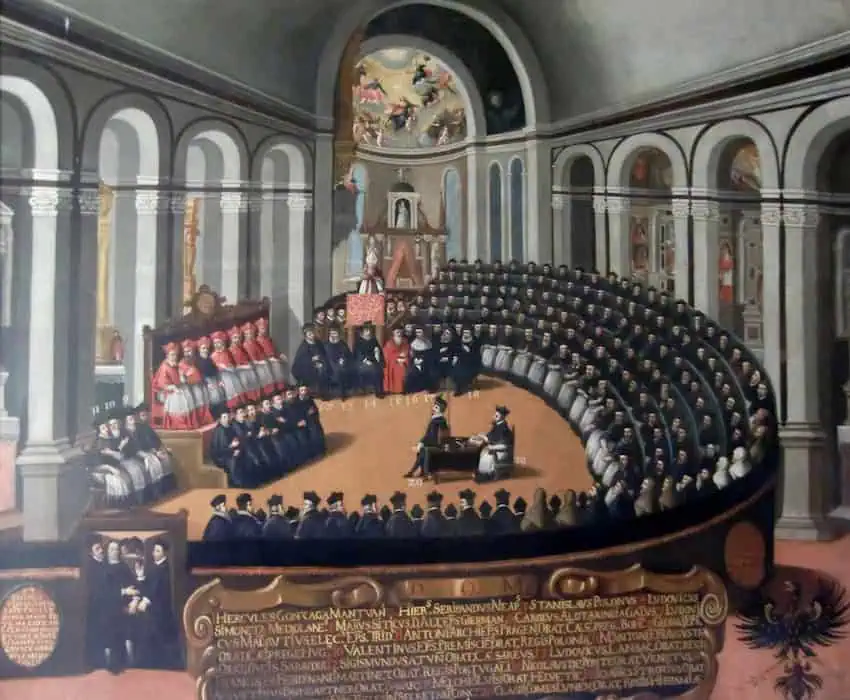

This changed after the Council of Trent in the 16th century when the Catholic Church mandated the systematic registration of baptisms, marriages, and burials. These records became crucial for the Spanish Inquisition, which used them to trace people’s ancestry in search of any “impure” lineages. The individuals the Inquisition sought to identify were primarily Jews and Muslims who had been forced to convert to Christianity and were often suspected of secretly practicing their original faith. To enforce religious conformity, the Inquisition meticulously examined family histories, sometimes going back several generations, to ensure there were no traces of non-Christian lineage.

As a result, ancestry began to be meticulously examined and extended to all four grandparents’ surnames, reinforcing the belief that individuals descend from their entire family lineage. Noble families emphasized prestigious surnames, especially those linked to inherited titles or wealth. Beyond social hierarchy, this practice also proved practical, allowing to more precisely identify individuals.

Civil registries and standardization

In the 19th century, civil registries were introduced by liberal movements that sought to shift population control from the Church to the State. The first formal registry was established in Madrid in 1822, and civil registration soon became mandatory for the entire population. This transition allowed the government to maintain a more systematic record-keeping system. The Spanish Civil Code of 1889 established the practice of passing down both the paternal and maternal surnames, solidifying the naming convention still used today.

The challenges of this system

While this system offers many advantages, it can become a nightmare in countries that do not accommodate two last names. Many must navigate a bureaucratic maze just to ensure their documents remain accurate. Some people choose to drop their second surname for convenience, only to later discover that their records no longer match across different systems. When filling out official documents with only one space for the last name, the first apellido may be mistaken for a middle name, the second apellido may disappear entirely, or both apellidos may need to be hyphenated into one for safekeeping.

Freedom of choice in a new era

In 2016, Mexico’s Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the requirement of children being registered with their father’s surname first, arguing that it reinforced gender inequality. This landmark decision granted parents the right to choose the order of their child’s surnames, allowing them to prioritize either the paternal or maternal lineage. A year later, in 2017, a case emerged where a couple successfully registered their child using both of their maternal surnames, further solidifying the legal precedent. Additionally, the ruling established that adults could petition to change the order of their surnames, providing freedom of choice in personal identity.

Honoring my parents

My surnames are rare enough that I could be accurately identified with just one. I choose to use both to embrace the wholeness of my being. I practice a balanced sense of self by acknowledging the male and female energies that created me. As the granddaughter of four courageous Europeans who fled the horrors of anti-semitism and found refuge in Mexico, my full name holds a legacy of identity and resilience.

A lasting tradition

Ultimately, Mexico’s two-surname tradition reflects a culture that values deep roots. So, the next time you meet a Mexican with what seems like an excessively long name, remember: it honors their ancestors and ensures that no Juan is ever lost in the crowd.

Sandra Gancz Kahan is a Mexican writer and translator based in San Miguel de Allende who specializes in mental health and humanitarian aid. She believes in the power of language to foster compassion and understanding across cultures. She can be reached at [email protected]