The construction crews were in a hurry. López Obrador had just canceled the half-built Texcoco airport and entrusted the military to build what would become Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA). However, there was one problem: Everywhere the crews dug, they turned up huge quantities of bones. Government archaeologists would have to be called in, slowing down an urgent infrastructure project. Little did they know, they had uncovered one of the richest Ice Age fossil sites in the world, an ancient treasure trove that would allow Mexican scientists to make remarkable discoveries about the country’s prehistoric past.

It started with a team of six archaeologists, but grew to more than 50 Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) specialists overseeing a construction project that had turned into a massive archaeological dig. They eventually found over 70,000 fossils from ancient mammoths, camels, horses, giant ground sloths, dire wolves, deer and other ancient megafauna — including bits of at least 500 Columbian mammoths.

The mammoth discovery that was made in Mexico

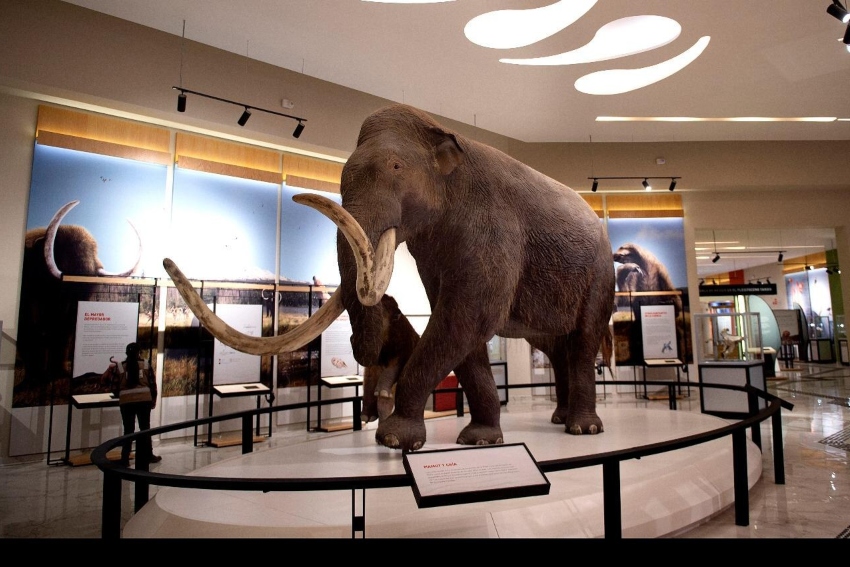

When most people think of mammoths, they imagine a woolly mammoth. Furry and relatively compact, woolly mammoths were well-adapted to living in the icy northern reaches of the Americas. Columbian mammoths, on the other hand, could reach four meters (13 feet) at the shoulder and weighed up to 12 tons. They were the descendants of the first mammoths to reach the Americas over a million years ago, long before their woolly cousins arrived.

Occasional fossil finds confirmed that Columbian mammoths roamed as far south as modern-day Costa Rica. But since ancient DNA tends to degrade in warm climates, most of what is known about them comes from northern populations. Before the discovery of the AIFA fossils, the genetics and evolution of these tropical mammoths were largely a mystery.

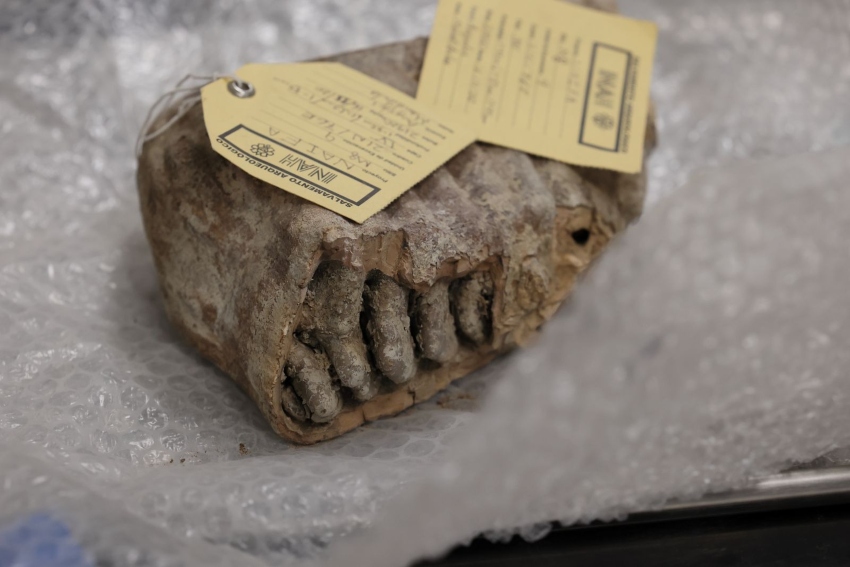

Access to the newly uncovered mammoth fossils was the opportunity of a lifetime for Mexican scientists, and they didn’t let it go to waste. A team of researchers from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) began working to extract ancient DNA from the fossilized mammoth teeth found at AIFA and several more found nearby in Tultepec.

The difficulties of doing DNA analysis on fossils found in the tropics

Very little ancient DNA has been found in the tropics, and none has ever been recovered from tropical mammoths. The delicate strands of genetic material fall apart quickly in warm, moist settings. But the UNAM scientists had a couple of advantages on their side. The Basin of Mexico fossil sites were both over 2,000 meters above sea level, providing a cooler, drier climate than elsewhere in the tropics. Another plus: After being dug up and exposed to air, fossils naturally begin to degrade. But in this case, the scientists were able to access the fossils quickly while they were still relatively fresh.

Paleogeneticist Federico Sánchez, one of the researchers at UNAM, said the team confirmed that the fossilized teeth found at the sites belonged to Colombian mammoths based on their shape. After that, he told Mexico News Daily, the scientists began drilling out dental dust samples for DNA analysis. The first surprise was the amount of genetic material they found. Tens of thousands of years after the mammoths died, over 80% of the teeth still tested positive for DNA.

They worried the dental dust might have been contaminated. DNA fragments could have come from bacteria on a researcher’s hands or even a breath of air that touched the sample, so they compared it with known mammoth genetic material. Once again, the tests were positive. When Sánchez saw the results, he knew they had something very special on their hands.

How new information was unearthed about the Ice Age past of the Americas

“It took my breath away for a moment, because I hadn’t been sure that we were going to obtain endogenous mammoth DNA, and much less from so many individuals,” he said. “It was a very special moment.”

As they analyzed the DNA, the researchers found something unexpected. The Basin of Mexico mammoths were very different than their northern brethren. In fact, the northern Columbian mammoths appeared to be more closely related to woolly mammoths than to mammoths of their own species found in the Basin of Mexico. A likely explanation, Sánchez said, is that northern Columbian mammoths interbred with woolly mammoths. Colombian mammoths arrived in the Americas over 100,000 years before woolly mammoths, so some may have moved south before having a chance to get it on with their woolly northern cousins.

The scientists also found a high degree of genetic diversity within the Basin of Mexico mammoths, possible evidence of earlier hybridization between woolly mammoths, Columbian mammoths, and, even farther in the past, the ancient steppe mammoths of Eurasia.

New insights into the social lives of ancient mammoths

The analyses even provided hints about what the mammoths’ social lives might have looked like. In other areas, there are more male mammoth fossils than females, possibly due to males leaving behind matriarchal social groups to wander off on their own, then dying in natural traps like swamps or tar pits — typical behavior for elephants and related species. In Mexico, however, the genetic sex of the fossils showed an equal split between male and female. That suggests that the social groups stayed together, so males and females faced the same risk of dying and becoming fossils.

The results, now published in the prestigious scientific journal Science, are groundbreaking in more ways than one. It’s one of the first times scientists anywhere have extracted DNA from large animal fossils in the tropics, and the first genetic analysis of tropical mammoths. In total, the team found more Columbian mammoth DNA than every other previous study combined, a resource that scientists around the world can now use for their own studies.

It’s a relatively new field of study for Mexican scientists, who have long excelled in archeology but have less of a track record in ancient DNA studies … until now.

Mexico’s first major megafauna genetics project

“It’s the first genetic study of megafauna in the country,” said María del Carmen Ávila, another UNAM senior researcher who worked on the study. “Having developed the technical capacity, human resources and infrastructure to do it here allows us to know more about our natural history.”

Another remarkable achievement was that much of the project was carried out by two ambitious undergraduate students. Ángeles Tavares Guzmán, who was studying biotech engineering, did most of the hands-on experimental work to extract the DNA. Eduardo Arrieta Donado, a genetics science student at the time the project started, did nearly all the evolutionary DNA analyses, Sánchez said. Together, Tavares and Arrieta are the lead authors on the article published in Science.

There’s still much to learn about the history of Columbian mammoths and the natural history of Mexico in general. However, thanks to this team of Mexican researchers, the country now has more tools than ever to tackle the problem.

Sánchez and other UNAM scientists are currently working to extract and analyze DNA from fossilized horses, camels, bison and deer uncovered during the construction of AIFA airport.

Studying the fossils of AIFA “has been a very thrilling and enriching experience from the start,” he said, “and we’re very excited for what’s coming next.”

Rose Egelhoff is a senior editor for Mexico News Daily.