Five months after he won a landslide victory in Mexico’s 2018 presidential election on promises to “transform” the country, leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador will be sworn into office on December 1.

The prolonged transition period – currently one of the the world’s lengthiest – has given Mexicans a preview of what presidential leadership will look like under López Obrador: aggressive.

Since its July 1 general election, Mexico has effectively been run by parallel governments with very different agendas. President Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico’s conservative and highly unpopular outgoing leader, has all but disappeared from the public eye, even as tensions with the United States over the treatment of Central American migrants run high.

Meanwhile, López Obrador has been increasingly visible, offering asylum and temporary work permits to refugees, pushing his legislative priorities and deciding the fate of major infrastructure projects – though, strictly speaking, he cannot follow through on any of these decisions until after his inauguration on Saturday.

The president-elect’s disregard for constitutional restrictions has many political analysts in the country, myself included, concerned about how he will use his executive power once in office.

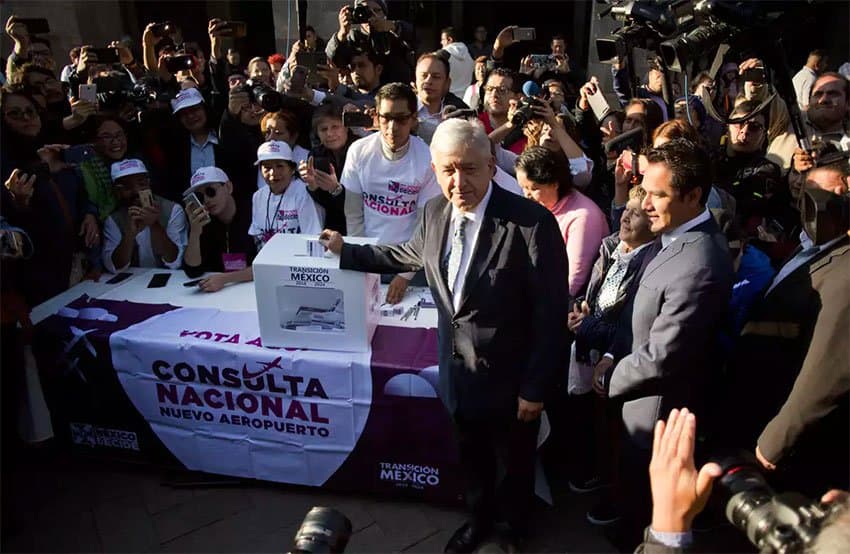

Since July, López Obrador has unilaterally called two “people’s polls,” circumventing a constitutional requirement that all popular referenda be approved by the Supreme Court and administered by the national election authority.

In October, his Morena party hired a private polling firm to ask Mexicans in 538 towns near the nation’s capital to vote on whether to cancel Mexico City’s controversial, extravagantly over-budget and environmentally disastrous – but much-needed – new international airport.

Seventy per cent of the nearly 1.1 million people who cast their ballots wanted to scrap the $13.3-billion project, which López Obrador had harshly criticized on the campaign trail.

Opposition lawmakers and protesters retorted that Mexican law requires a 40% voter turnout for a popular referendum to be considered binding. López Obrador polled 1.1 million people in a country of 130 million.

Nonetheless, the president-elect immediately announced the termination of the airport project in favor of revamping an unused military airport north of the capital.

As engineers, academics and the business sector also denounced the decision to scrap the new airport, the Mexican peso plummeted amid investor concern about national stability.

AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo

López Obrador responded to criticism with a populist evasion, saying simply that “the people are wise.”

A month later, López Obrador’s transitional government called another unconstitutional referendum to decide the fate of another major infrastructure project. In late November, 900,000 voters determined that the Mexican government should build the Maya train, a 1,500-kilometer rail line that would connect five southern Mexican states and the Yucatán peninsula.

Not consulted prior to the referendum: the Mayan communities traversed by the proposed railroad and who, by law, must be included in all decision-making that impacts their indigenous territories.

Nonetheless, López Obrador has declared that the rail project will be completed by the end of his six-year term.

López Obrador’s misuse of direct democracy to expand his executive powers while not even president sends worrisome signals about how he will govern Mexico.

The Mexican presidency is already an enormously powerful office. It was designed that way in the 1920s by the authoritarian Institutional Revolutionary Party, known as the PRI, which ruled the country virtually uncontested for nearly the entire 20th century.

After 80 years in power, the PRI lost the presidency in 2000 but was restored to power with President Peña Nieto in 2012.

López Obrador, a former Mexico City mayor who has unsuccessfully run for president twice before, won this year in large part because he promised to make Mexico’s centralized, stagnant political system more inclusive and consultative.

He pledged to root out corruption, reduce violence, restructure Mexico’s energy sector, respect the human rights of migrants and spur growth in the country’s most impoverished areas.

Legislatively, López Obrador will have the power to push through his transformative agenda.

His political party, Morena, secured majorities in both the Mexican Senate and lower Chamber of Deputies in July’s election. That also gives López Obrador the right to replace up to two justices on Mexico’s Supreme Court.

But some recently announced policies have surprised Mexicans who thought they elected a leftist champion of workers rights and social inclusion.

As part of his plan to slash public spending and eradicate corruption, López Obrador has released an austerity budget that includes laying off 70% of non-unionized Mexican government workers. An estimated 276,290 public employees will lose their jobs, according to Viridiana Ríos, an expert on the Mexican economy.

Bureaucrats who remain will be asked to work from Monday through Saturday for over eight hours a day.

López Obrador justifies the downsizing by quoting Benito Juárez, the celebrated indigenous president who ruled Mexico from 1858 to 1872. Juárez thought public officials should live in “honorable modesty,” avoiding idleness and excess.

Few doubt that Mexico’s government bureaucracy is bloated, and that expunging the rampant corruption of Peña Nieto’s PRI will require serious restructuring. However, the working conditions López Obrador proposes violate Mexican labor standards, which guarantee job security and an eight-hour work day.

There’s a logistical problem here, too. Implementing López Obrador’s ambitious policy agenda asks a lot of Mexico’s federal government. The president-elect now intends to transform his nation with an underpaid, overworked and understaffed bureaucracy.

López Obrador has angered other supporters by breaking a key campaign promise.

As a candidate, López Obrador pledged to reduce violence in Mexico by de-escalating the country’s war on drugs. Rather than using soldiers to fight crime, as Mexico has done since 2006, he said he would professionalize the Mexican police and grant pardons to low-level drug traffickers willing to leave their illicit business.

The security plan was underdeveloped, and when pressed for details on the campaign trail, López Obrador simply responded that Mexico needs “justice,” not “revenge.”

But voters recognized the sound logic behind his diagnosis. Numerous studies show that Mexico’s military crackdown on organized crime actually caused violence to skyrocket.

The number of criminal groups operating in Mexico surged from 20 in 2007, the year after the full-frontal war on drugs began, to 200 in 2011, according to the Mexican university CIDE. By last year, Mexico had 85 homicides a day – the highest murder rate since record-keeping began in the 1980s.

López Obrador has since radically changed his strategy for “pacifying” Mexico.

On November. 14, the president-elect released a National Security Plan that continues to rely on the Mexican armed forces for fighting crime. Lawmakers from his Morena party have introduced a bill to create a National Guard, a new crime-fighting force that would combine military and civilian police under a single military command.

Mexican political pundit Denise Dresser has dubbed López Obrador’s strategy as the current cartel war “on steroids.” Security expert Alejandro Madrazo wrote in The New York Times that the decision is a “historic error” that squanders the opportunity to have a national dialogue about the role of the military in law enforcement.

Mexicans gave López Obrador a mandate to revolutionize the government so that it finally works for them. The president-elect’s power grabs, austerity budget and U-turn on security are early signs that he may not deliver the transformation they so eagerly await.![]()

Luis Gómez Romero is a senior lecturer in human rights, constitutional law and legal theory at the University of Wollongong. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.